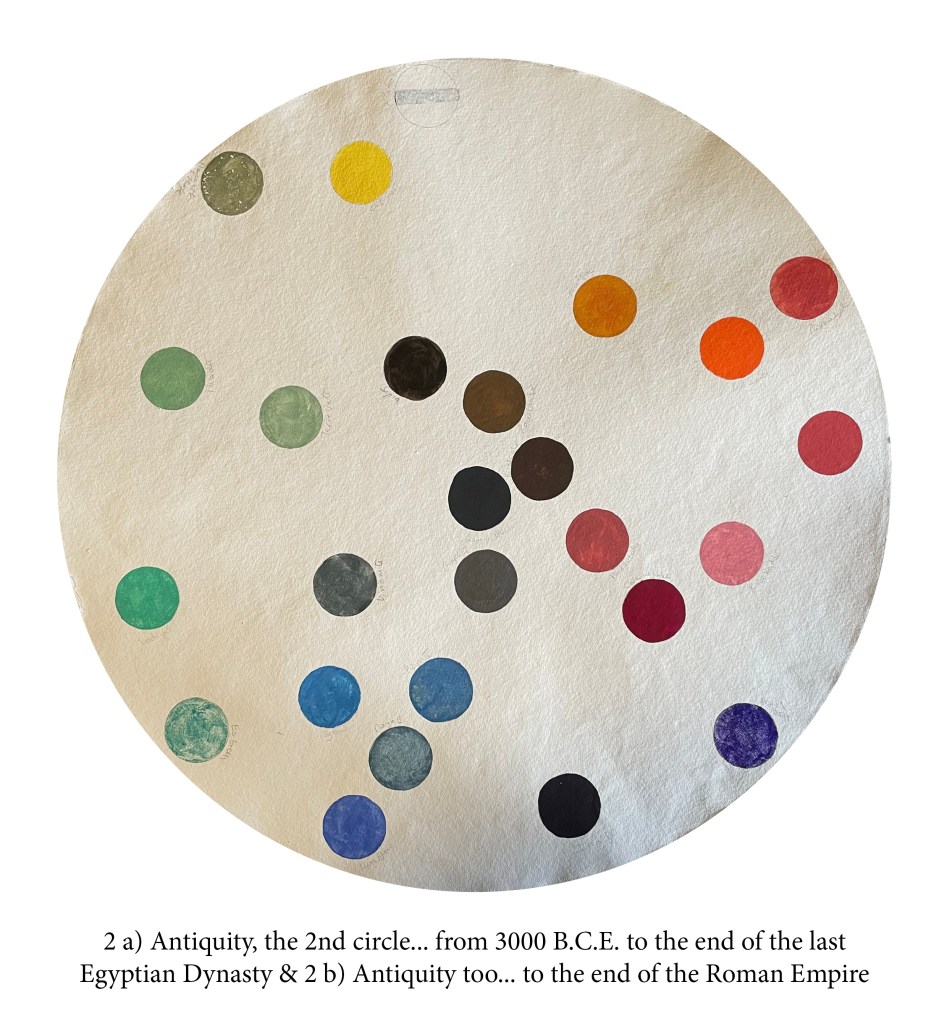

I thought it might be interesting to be able to scroll down the chronology of these 88 pigments… and have added a little story about each, just because…

(Although most of that information is available elsewhere in the book, it is scattered and might be easier to access thus.)

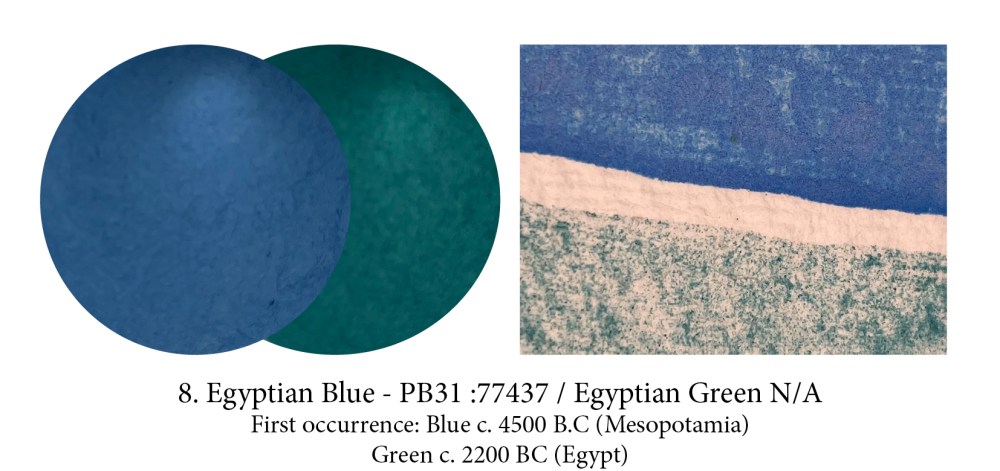

Meet our first ever artificial pigment! This recipe, probably discovered in Mesopotamia, was used throughout Antiquity… and then was lost (or demand had become so scarce that it simply wasn’t made anymore and forgotten). This frit pigment, the Romans called caeruleum, is not glassy but crystalline and is made from calcining copper or bronze powder with quartz sand and limestone in the presence of a potassium or sodium flux… in fact the hardest ingredient to find was the wood needed to keep the kiln burning at 950ºc for 2 days! If the temperature is lower you get green, higher… it turns black.

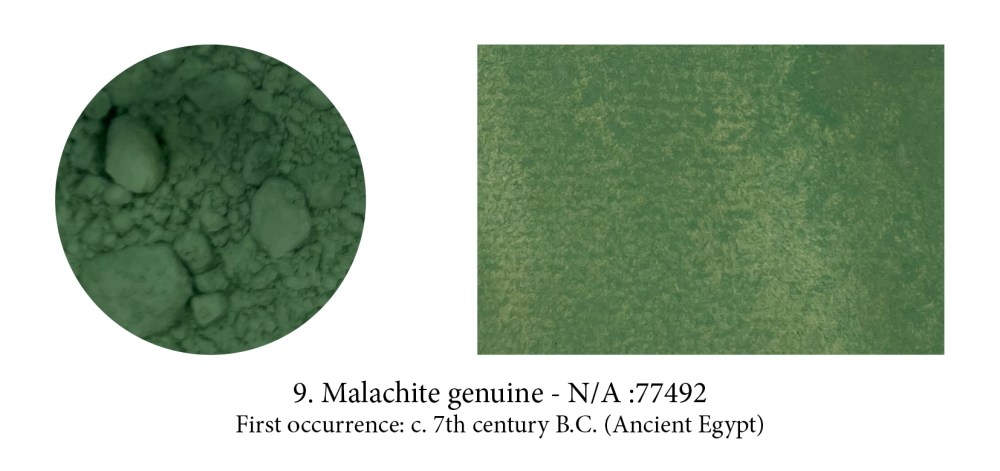

A copper carbonate hydroxide mineral, Malachite was used in Ancient Egyptian painting and particularly in the context of female “green-faced” coffins from the 26th Dynasty. Its green colour was only available in a coarse grind and the pigment turned weak in oils where a finer pigment was needed. Nevertheless, it was still used, layered for effect of its different hues and in a lot of binder in the 15th and 16th centuries… the binder has often reacted to the copper however and discoloured.

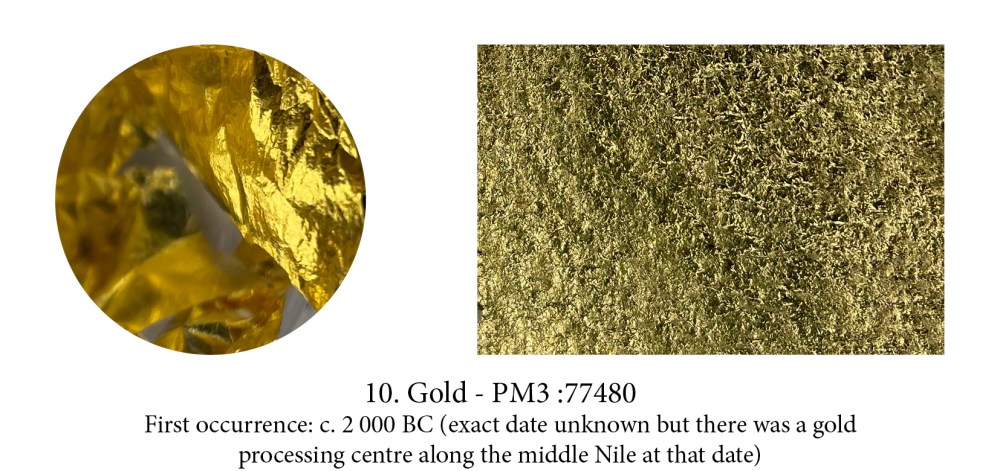

Gold is a peculiar pigment that needs pounding and hammering until it is the finest of leaves. These are then glued to a support, burnished to a shine and often enhanced further with incised or drawn patterns. You can turn gold into a watercolour paint (a tedious process) and, as it was once stored in shells, it kept the name of Shell Gold. Manuscripts were illuminated – literally and metaphorically – by gold and silver. The precious metals dazzled the eyes and embodied the most mysterious of God’s creations – light.

Found in nature as a mineral, this yellow arsenic sulfide was known to the Greeks as arsenikon and related to the Persian zarnikh based on the word zar, Persian for gold. Orpiment obviously too simply means gold-pigment. Known since ancient times, used in Persia and Asia as a paint, it was

exported from the Yunnan province of China and used at first in Egypt as a cosmetic (not a great idea) as well as, later, as a paint. Despite its toxicity, and the fact that it smells foul, it remained incredibly popular in Medieval illumination.

Cinnabar is a bright red natural mineral: chemically, mercury sulphide. Mined in southeastern Europe as early as 5ka and used profusely by ancient Chinese alchemists in medicines as it was

thought to have almost miraculous properties, also because the liquid metal mercury could easily be extracted from it by heating. The toxicity of the mineral was well known to the Romans and workers in the Almadén mines, in Spain, were slaves or convicts, yet its beautiful red was irresistible. The most expensive pigment found at Pompeii, Cinnabar was brought from there under guarded escort.

Graphite would one day overtake charcoal as a primary drawing tool and make a name for itself. At first, however, it was thought to be lead (some still insist on buying lead pencils!) and went by the name of plumbago, from the Greek, meaning to write as this pigment is more literary than painterly!

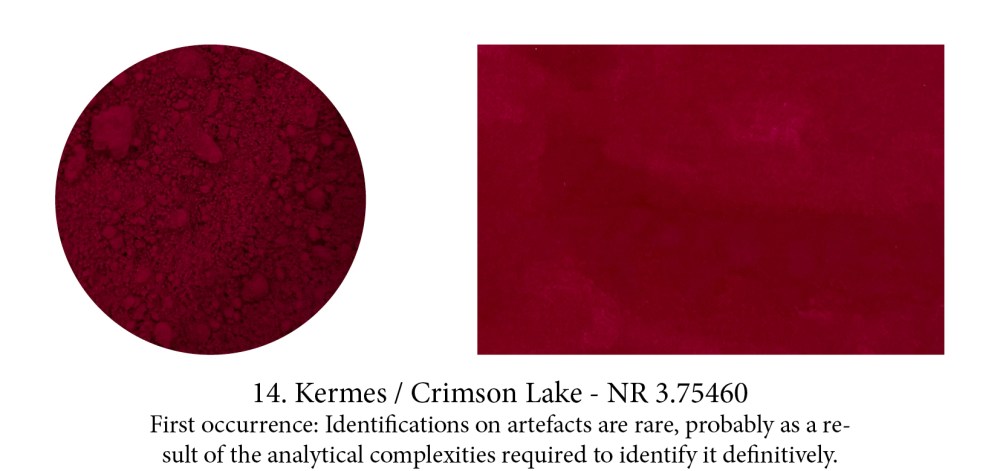

Crimson and Carmine are both derived from the Armenian word kermez which means “little worm” — that little one living on leaves of holm-oak and Kermes shrub oak named after it. Crushed, it

releases a beautiful red substance used since at least 2000BC around the Mediterranean to dye cloth or, turned into a lake pigment, to paint with. We were well satisfied with it too until we met coccus cacti, its even more powerful American cousin — another parasite that cochineal one, which feeds off cactuses as its name implies.

Although soot has been used since prehistoric times to make black marks, and ink has been developed just about everywhere on the globe at some stage or another, Indian ink actually comes from China (its French name: Encre de Chine, is the correct one!) It was developed there in the middle of the 3rd millennium BC. replacing plant dyes and graphite which had been used for centuries prior but produced rather greyish results. The new process consisted of allowing little oil lamps with a conic hat to burn until all the oil had disappeared, the lamp left to cool, and the soot then collected. That pigment, mixed with animal glues, would then be kneaded and beaten until it was smooth and malleable enough to be moulded into cakes. Left to dry, the practical little sticks would produce ink-on-demand all over the Empire just by adding water.

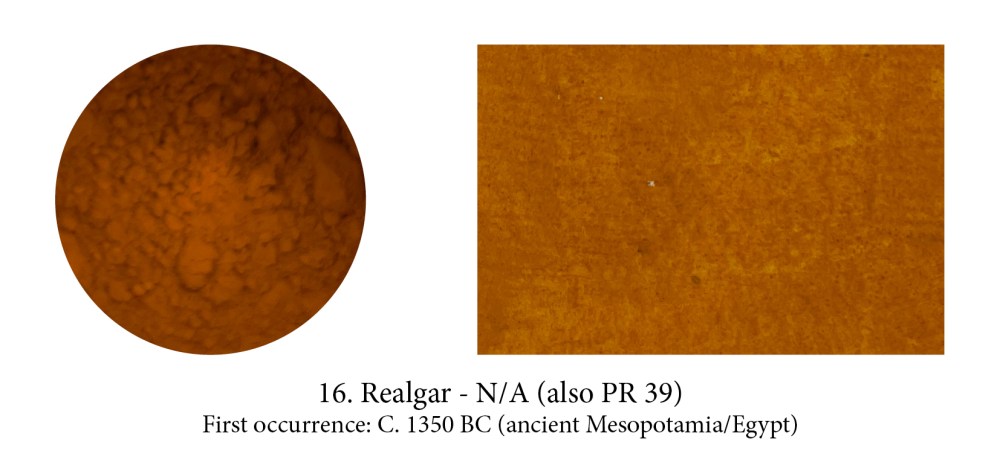

Orpiment and Realgar, both natural pigments, are often found together and their Chinese names —“feminine yellow” for Orpiment, “masculine yellow” for Realgar — reflect that.

Realgar, an orangey-red pigment which I always thought sounded pretty regal, actually means in Arabic from which it comes: “rat poison” and with the mineral containing naturally 70% arsenic, yes I think it would have been most efficient indeed! Yet, we had to use it… if we wanted the colour that is, as Realgar was the only pure orange pigment until modern Chrome Orange.

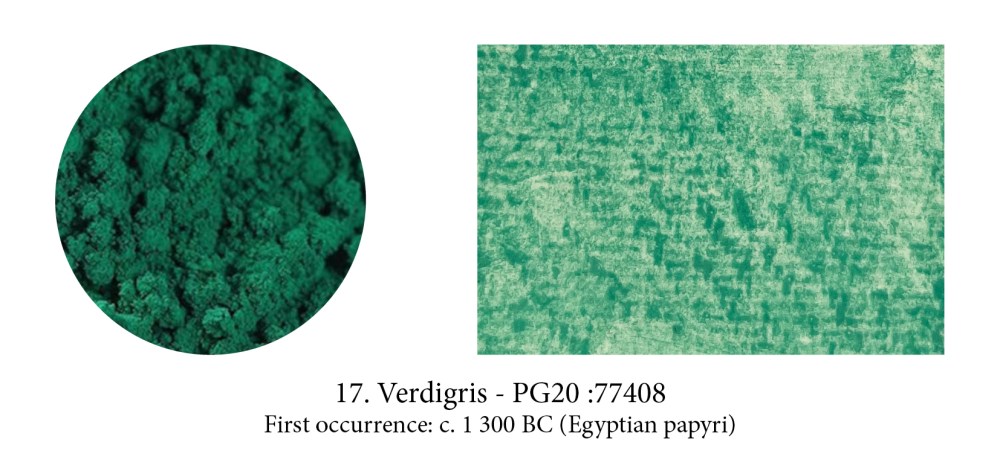

Very many pigments contain copper but Verdigris — from the French Vert de Greece (green from Greece) — is the sun of this blue/green constellation! Until Arab alchemists brought to Europe in the Middle Ages strong acids like sulfuric and nitric acid, it was made by suspending copper sheets above vinegar (+/- salt) and wait until Copper oxide is formed. Verdigris is pretty undefined as it applies to quite a few different corrosions and its colour, as a result, can vary too. Mine here was made by Lucy from “London Pigment” from Victorian copper scraps from the foreshore of the Thames, reacted with vinegar.

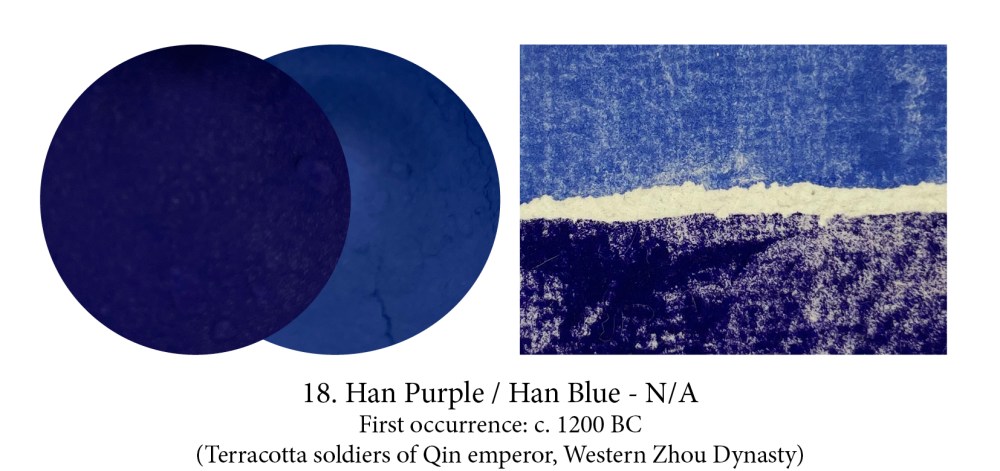

Both Han Purple and Han Blue were barium copper silicates which could be mixed to produce intermediate hues, yet they differed in their formula, structure, and chemical properties. Han Blue is remarkably similar in composition and manufacture to Egyptian blue (a calcium copper silicate, however), if slightly less fluorescent.

Their colour happens in the kiln too, not from a variation in temperature though (900°C will do), but from patience. Han Purple forms first, in around a day, but double the firing time and it will break down and release the blue. What mastery there too!

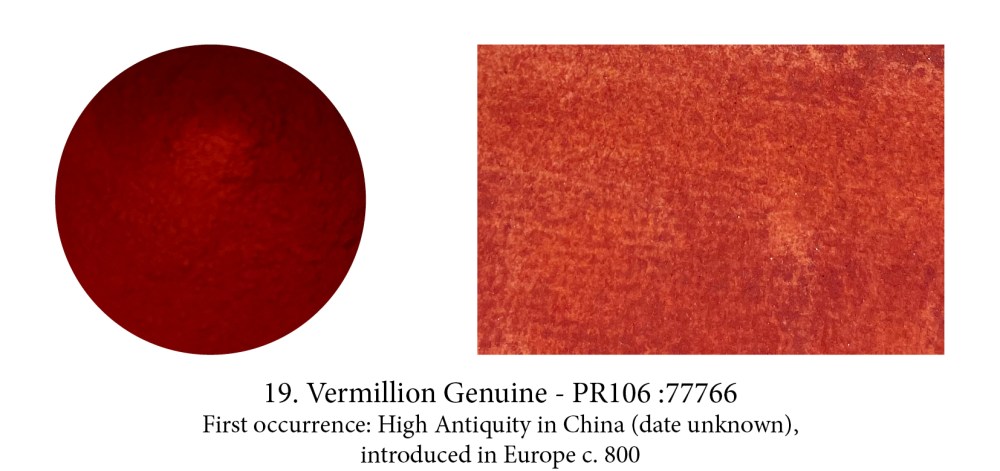

Some would argue that the innovation most critical to medieval painting was the synthesis of cinnabar, which became known by the name Vermillion — a truly alchemical affair! Imagine combining mercury and sulfur to create a black form of mercury sulfide which, once pulverised and sublimated by intense heating, turns into a divine red that could be sold for its weight in gold… You might even believe you’ve found the philosophical stone itself! Apparently too, the finer you ground this black, the more powerful the red would become… how entrancing.

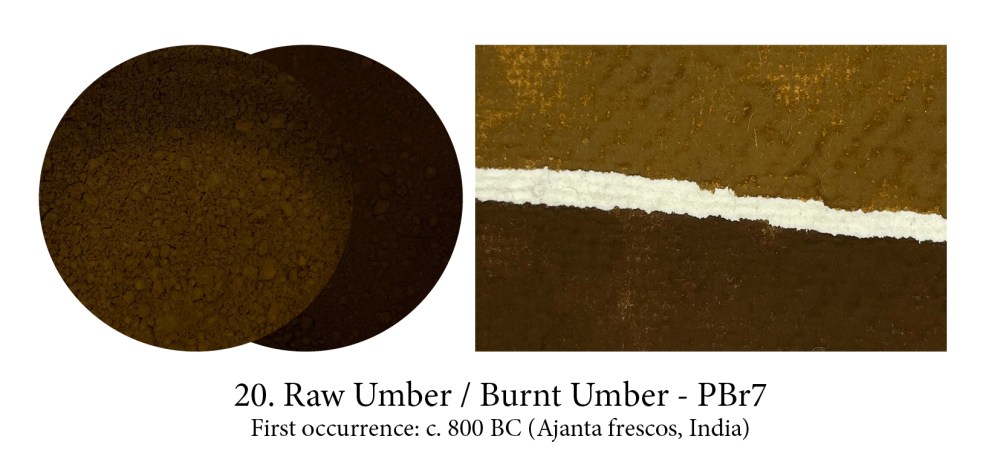

Umbers contain between 5 and 20% manganese oxides and between 45 and 70% iron oxides. They are rich, warm brown colours which usually sit next to the Siennas on paint racks. However, if these are/were, indeed, from the region of Sienna, the Umbers don’t get their name from Umbria. In Italian, it refers to the shadows they were useful for, and I should have understood that long ago as in French, Burnt Umber is Terre d’ombres brûlée. When I finally understood that, I loved its

potential English translation: Raw Shadows, Burnt Shadows. Beautiful, romantic. One could even venture aromatic…

The cuttlefish was — both it and its inky secretion — called sepia in Latin, and despite the fact you could obtain black ink from the octopus and blue ink from the squid, it seems that golden brown was the winner of the Art ‘ink bag race’. These sacs, carefully extracted and sun-dried, were boiled in a solution of soda or potash in which the colour would dissolve. Once filtered, it was precipitated by the addition of acid. Today it’s really only a colour name (no cuttlefish!) but in the 19th century Sepia became so fashionable to draw with, that it partially displaced Indian ink and Bistre.

I have chosen to illustrate two of the most famous hues available to artists, however, madder roots can give dyers an infinity of pinks and reds. Being Lake pigments these were never lightfast and yet Rose Madder had such following in watercolour that it is still made today (only by Winsor &

Newton). It’s synthetic counterpart, Alizarin Crimson, is (not as) fugitive… but still!

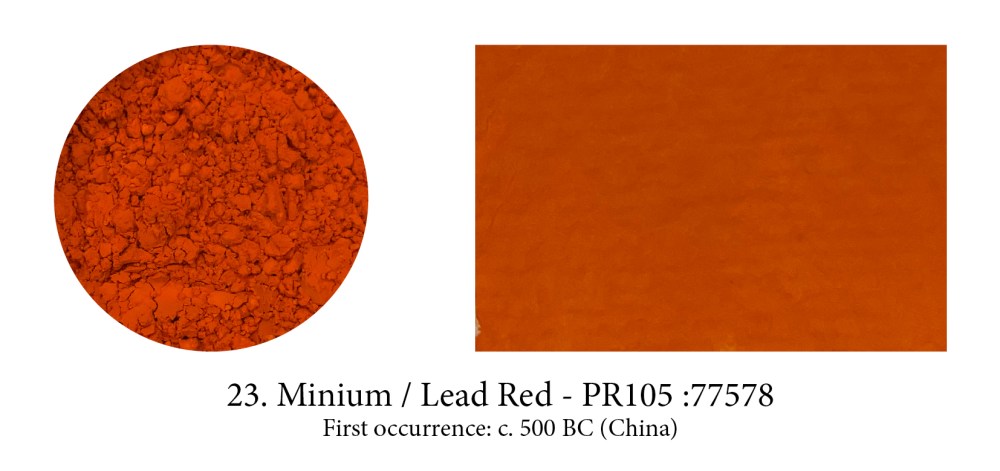

Minium is Lead Red’s natural mineral counterpart, while this artificial one is made just like Lead White, then roasted to a beautiful bright orange (despite its name and it being classified as red.) Pliny called its colour flammeus (flame color) but the pigment was not very happy in frescos where it turns black, until oils, in which it is quite stable. It was used more on paper both in Asia/Persia and, later, in Medieval manuscripts often in conjunction with the more expensive Cinnabar and Vermilion.

Litharge is hardly a useful pigment (its greenish yellow hue is depressing), it grits and doesn’t bind well (as it contains large lead pieces) and it’s toxic… so how did it even make it on this short list?

Well, the thing is, it’s an amazing siccative and was often added to cooked oils, walnut and linseed, when colours were blended or varnishes were made. So… it had its use!

Lead white answers to many names… from its lead component, to its texture: flake (3 months of vinegar vapours will do that!), to its colour: silver, to where the lead came from: Cremnitz or where it was made… Rublev’s oil paint range offer 9 different ones made via the original “stack process” or not, in linseed or walnut oil, etc.

Painters still use it —carefully we hope— despite its toxicity because, unlike Zinc, it’s fast drying and, unlike Titanium, it doesn’t ‘kill’ the other colours!

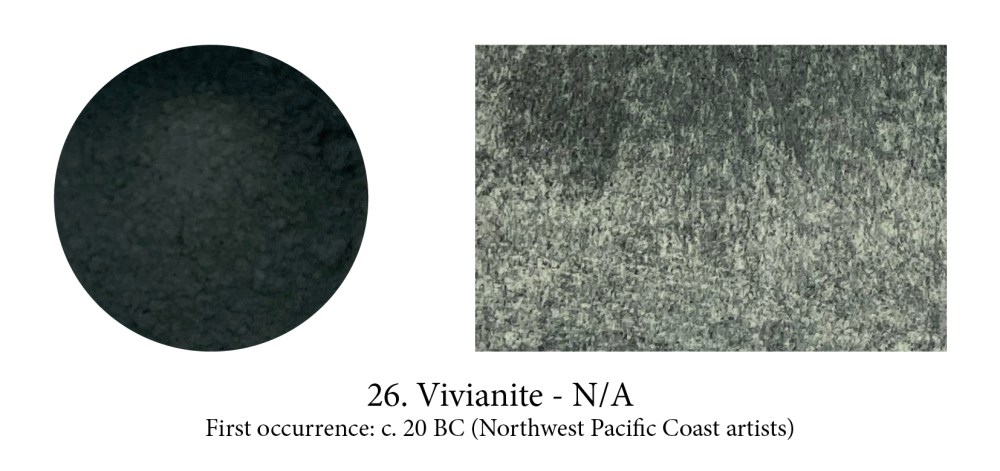

Vivianite is a most curious one belonging to the group of magnetic pigments… It often goes by the name of Blue Ochre and, yes, it is an Earth pigment but not an ochre. It’s an aqueous iron phosphate that looks like almost transparent glass and only takes on its blue-gray color when ground. In paint it interestingly shifts from grey to blue to green. In 1979, the nearly complete mummy of a bison covered with a blue chalky substance was found in Alaska. That mineral coating of white vivianite was produced when phosphorus from the animal tissue reacted with iron in the soil. When the vivianite was exposed to air, it turned to a brilliant blue, earning the bison the nickname Blue Babe.

Indigo is a rare one. Despite its undeniable colouring properties in the vat and most of us knowing indigo as a dye, it is, in fact, a pigment. Oh, a lake pigment then. No, a real pigment, a babe which indeed cannot be dissolved into oils, resins or water, so correctly labelled as pigment. You can grind indigo cakes into particles fine enough to be milled in oil or dispersed in water and turn these into paint without need for further processes. The paint produced thus is a rather poor one which was often used however as an alternative to more expensive blues.

Green earths or Terre(s) verte(s) are green-coloured due to concentrations of the clay minerals celadonite or glauconite. Although derived from a mineral source, Terre Verte is not a natural

iron oxide pigment, but an iron silicate with clay. For centuries, Terre Verte was mined near Verona in Italy, hence its other name ‘Verona Green’. This deposit is near exhausted and it mostly comes from

Cyprus now. Extremely transparent, it has a low tinting strength. Its claim to fame was as a perfect underpainting colour for flesh tones, acting to neutralize them, and can be noticed often in tempera

paintings where the reddish/pink layers have faded.

To be fair to indigo, it must be said that it can make a wonderful paint… if you improve the recipe. It also requires a rather rare ingredient, attapulgite, a very white type of palygorskite clay but once you find it, you can turn it into one of the most durable, lightfast pigment existing. The first fragments were found on Mayan artefacts, and promptly baptised Maya(n) Blue. Analyses

deemed it a clay. (Indigo is virtually insoluble in almost all liquids and solvents remember, so pretty hard to analyse.) It took more sophisticated investigation equipment to understand the unique chemical bond of indigo-dyed-clays… and the right temperature for our recipe! On its way to

300c, indigo molecules dissociate and enter the nanotubes of this particular clay and bond with them, a reaction irreversible. Higher temperatures will give you, as with the dye, endless variations of the blues!