WHAT?

II. What’s in paint?

B) Binders

After this cycling detour, let’s go back to the beginning… oil will have to wait for quite a few centuries (millennia, to be fair) and have a look at binders in order of appearance.

In most cases, it is hard to trace thousands of years back which binders have been used… if any. Whether they lasted a day on the skin, a lifetime under the skin or a few generations on the surface is anyone’s guess. Today’s archeologists and art historians try not to guess (too much) so that Art begins with surviving works…

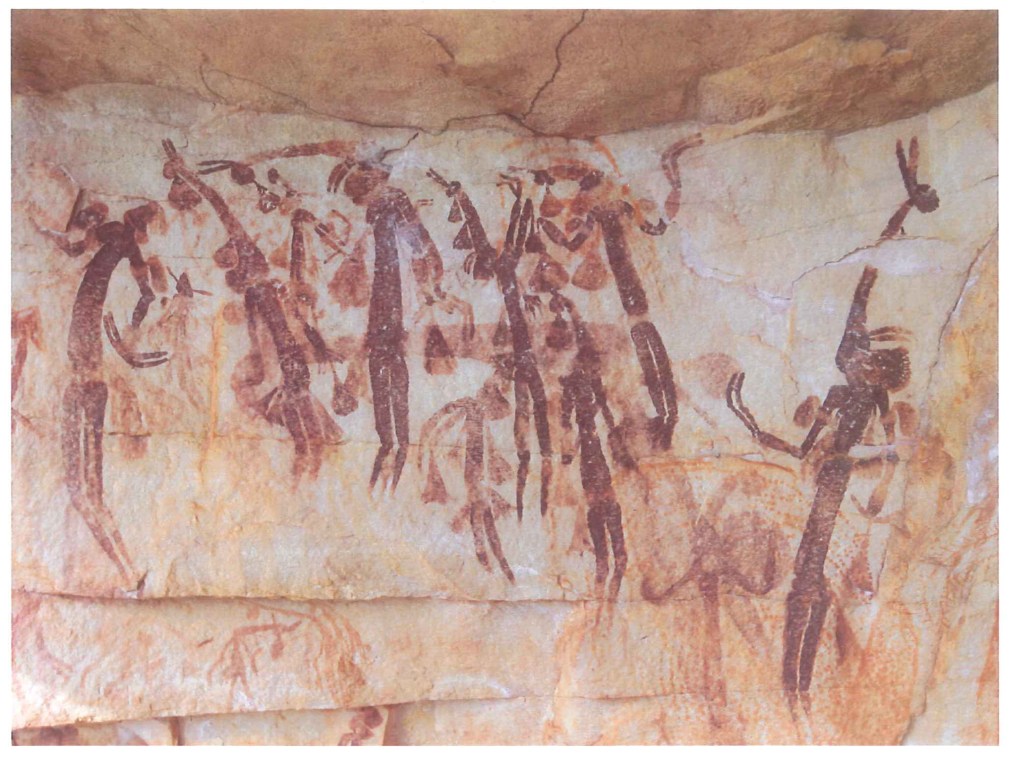

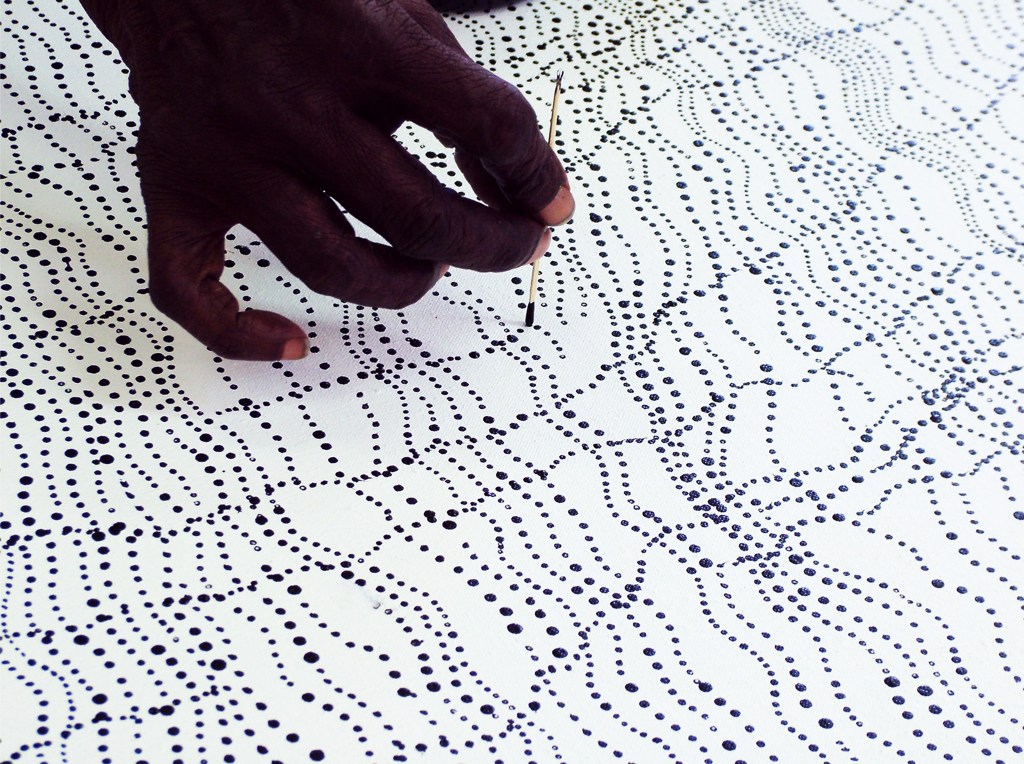

We know, for example, that Aboriginal Australians often used animal fats, beeswax, egg, resins and, in some areas, the gooey sap of a local orchid, which worked well for their bark painting, but we mostly know that because they were still using these binders quite recently. Actually, in the case of most surviving works, it is the support that has been decisively crucial to the preservation of the artwork. The rock wall has absorbed the paint so thoroughly that it has literally amalgamated the pigment.

As a result—Earth pigments being inorganic and thus undatable—Australian rock art is highly tricky to date. Nevertheless, sometimes archeologists have a lucky day, as in the case of this rather ‘precise’, if most unusual, datation which became recently available… Have you ever wondered what the point of wasps was? Well, now you’ve got at least one good reason to be thankful for their existence, as a finding of fossilised mud wasps’ nests in the mysterious rock figures of the Gwion Gwion in the Kimberleys, some caught under the paintings, some above, has helped determine both maximum and minimum age constraints for these paintings and put the date of these works back to 12,000 years ago.1 How? Well, when the mud wasps collected sand off the ground, they also encapsulated in their nests tiny pieces of charcoal from dry season burns, mixed with sticks, pollen and insect shells (Organic! Alive once! Datable!), turning these into tiny time capsules… of sorts!

Remoteness and specific geological and climatic conditions have thus preserved some works here and there on the planet. Probably many more have been created by our ancestors, making each of us the legitimate great-great-great-great grandson or granddaughter of a painter… who knows? What I do know, though, is that the Balanggarra people, who are related to the people who did these Gwion paintings, are still here today in Australia… and, some of them, no doubt, are still painting. (And that gives me the shivers.)

But back to our paint binders. To increase the bond, pigments can easily be mixed with all sorts of glues Nature offers generously, which were probably quickly discovered as… when things stick… they stick! Some must have been obvious finds: fat, honey, blood, saliva, gum, sap, resins… some are a tad more mysterious. How did we discover that fish bones and a rabbit’s skin could make excellent binders, I wonder? (Then again, I’ve never skinned a rabbit nor had to deal with vast quantities of fish bones, as I might have discovered that these were sticky substances.)

Many other ‘glues’ have been used as binders, some decidedly on the odd side… garlic juice as a mordant for gold, ear wax as part of the binding agent of pigments in medieval illuminated manuscripts, while a certain Benjamin West’s Spirit Varnish concocted by the man himself bragged a mix of mastic varnish, poppy seed oil and spermaceti (a waxy substance found in the head cavities of sperm whales!)2 It was all a trial and error game, really, and indeed not rare for a painter and his atelier to have and to hold a secret recipe very close to their palette, sorry meant their heart, of course (same thing!) Apparently, some oils performed better anyway if they were warmed up slightly so artists would keep them close to their bodies while in use, which is not why we call Bodied oil by this name, however. That one is simply a heat-thickened linseed oil with… a heavy body. Others call it Stand oil, a name given to the same oil from having to stand, back then, literally for months on end, in large vats.

If you were to draw historical circles for the binders, as we’ll soon do for pigments, you would discover quite a different story… Some of these binders, glues or agents have been replaced by synthetic ones that have more or less the same properties, but unlike pigments, so many of which are now forgotten and unused, we haven’t found a better oil than linseed nor a new type of egg that performs better than a chook’s.

The Egyptians already used gum Arabic, a most peculiar secretion of certain acacia trees, and gum tragacanth, from the dried sap of several legumes of the genus Astragalus from the Middle East, to make their paint, a distemper of sorts—wax and the resin of Pistacia lentiscus, better known as mastic, too but primarily as varnish. For their ‘encaustic’ portraits on board, the Greeks used pigments in melted beeswax alone or with added resins, and sometimes a tempera technique also involving wax. Orthodox icon painters found that eggs worked well but even better with a tad of oil. Eventually, oil took over the Art world… until polymer emulsions—acrylic and vinyl—challenged that position around 1953.

It was not a straight road; formulas were forgotten, artists died with their secrets while others tried ridiculous things. But overall, and over time, we have simply added one extra binder after another to our toolbox, ending with today’s variety of options.

P.S.: You might have noticed that I haven’t included casein. Truth is, I’ve no idea which period to precisely assign it to. Cheesemaking goes back a long way, so curd was available at least 7000 years ago, and many sources mention the Egyptians; some even suggest casein was used in prehistorical cave painting—supposedly using human rather than sheep or goat’s milk!3 Despite these ‘interesting’ leads, I seem unable to find artworks that would precisely date that binder medium, sorry.

Jump to the next section of the book by clicking here

Alternatively click on the Table of Contents to browse the sections.

You can also subscribe to my blog at the bottom of this page,

and you’ll receive Hues in Tubes in your inbox… as it gets published!

Additional information & references

- Even that date is still debated , as these mysterious figures are still the subject of much speculation about, perhaps, a much older civilisation . [Online]. [Accessed 13 November 2024]. Available at: https://www.abc.net.au/news/science/2020-02-06/gwion-rock-art-in-kimberley-dated-using-wasp-nests/11924584

↩︎ - These ingredients make me think it might have been both varnish and medium, (probably not as a binder medium alone, though) which is why I’ve included it in this list…. and of course, because it was irresistible! ↩︎

- It could work!! “The level of total protein in [human] milk is approximately 0.9 – 1.2%, of which approximately 70% is whey protein and 30% is casein along with small amount of proteins associated with the milk fat globules.” [Online]. [Accessed 13 November 2024]. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/food-science/human-milk-proteins ↩︎

Discover more from in bed with mona lisa

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.