WHAT?

II. What’s in paint?

B) Binders

Right: Andrew Wyeth, Helga Series – Campfire, 1982. Collection Leonard E.B. Andrews

Are you not amazed at the difference between these two paintings by Andrew Wyeth? Same talent, same subject, virtually the same angle, but the one on the left is painted with tempera on masonite and the other with watercolour on paper. The density of the board, the finesse of the tempera vs the looseness and the lightness of the watercolour dancing on the paper. Both are accomplished works, no doubt, but the different paints make them such different works! Do you have a preference? (Hard to choose, isn’t it?)

Obviously, you cannot play with all the materials and paints (I do, but then… I’ve bought the shop!) Still, don’t panic or despair in art stores, either. Slowly, you probably will build quite an art supplies “wardrobe”, with some shoes not often worn, some evening dresses once a lifetime, and some tees every other day! Nevertheless, it is your choice of materials that will dictate your working practice and results, and most artists tend to have a drug of choice they will defend wholeheartedly. Yet I have seen some who, after playing for years with a specific paint—its grounds, mediums and finishes—will change at some stage in an effort to find another medium that best reflects their vision at that time. And we are so lucky these days to have so many options.

(Before we go any further I believe it might be useful to clarify the word medium. You’re a painter? Correct? So your medium is paint, as opposed to clay, stone or musical notes. As the definition goes, it’s your “channel of communication”. You’re also a painter who paints in oils, so you understand that the binder medium of your paint is oil. But to move around this rather sticky and sometimes downright stiff paint, you’ll need… mediums (rarely used in the usual plural, media.) Because: “Oil painting without media, or with only linseed oil and turpentine, is like going to a French restaurant to order boiled duck, no sauce. An appropriate medium does for oils what a French chef does to an otherwise bland and greasy dead bird, and the results, like Duck a l’Orange, are exquisite.”12

Are all these usages of “medium” a tad confusing? Yes, they are, which is why I thought it worthwhile to point out the linguistic overlap which mirrors the significant overlap between binder mediums used to make paint and the ingredients in the mediums you use to push your paint around.)

So, let’s now dive into these options.

Water

Water, as just said, is a vehicle, not a binder.3 Nevertheless, to celebrate and colour the body, ochres and clays mixed with water are all that was and is needed. That ‘paint’ will stick to you and your hair for a short time at least. It might even, given the right environment, permeate a moist wall, a paper, a textile and do a lasting job.

However water, that nonstick vehicle, is also a main ingredient in all waterborne paints, from gouache to acrylics to watercolours, precisely. You would not be able to use a dried pan of watercolour if you couldn’t rewet it with water nor extend your acrylic paint without it. More importantly, would you be able to make the above paints without water in the first place? Nope. Yet water alone will not do the trick. (To be fair, even if you add some of the binders below, you might still need some other ingredients to make a perfect paint, but let’s not get bogged down in preservatives, additives, driers/siccatives, etc. just yet, as we will mention more on these when we get to our Paintmaking section, and, too, some are optional and mostly a choice paintmakers will make, not one you will have to make.)

Gums

“We all use and consume gum Arabic every day. It is irreplaceable in soft drinks. It is a key ingredient in inks and paints, it sticks the coating on glossy magazines and the chocolate pastilles that melt in your month but not in your hand. It is used in cosmetics and gel capsules, in lithography, and to form chunks of cat food and fertiliser. It is a component of matches and explosives. It is added to milk to make it creamy, to vegetarian meat to make it tender, to wine to make it clear, and to beer to make it foam. It helps make jams and cream cheese thick and chocolate high in fibres but low in calories. It is even found in toothpaste and in the glue for dentures. It turns up in stock cubes, instant-dessert powders, laxatives, tobacco, icing and ice-cream, sweets and insecticides.”4

Thus begins one of the most formidable odes to a material: Gum Arabic, The Golden Tears of the Acacia Tree by Dorrit van Dalen…

Gums, all gums, are essentially polysaccharides that naturally exude from the stems of a variety of plants, especially fruit trees. Although resins also ooze from plant passages and cavities… don’t confuse them (even dictionaries do) as resins dissolve in alcohol, not in water, while gums dissolve totally in water but not in alcohol. We will soon encounter some natural resins, but they are rarely used as paint binders. Gums, when dissolved—especially the magical gum Arabic, which does so perfectly (Gum tragacanth from Iran and karaya from India do not dissolve as well)— form a film around the nanoparticles of pigments, which keeps them afloat in liquids. When the liquid evaporates, however, that film will adhere to a surface. You can rewet it on that surface, up to a point, and in concentrated formulas such as your watercolour and gouache cakes and pans.

The Egyptians understood this perfectly and used it in their paints and cosmetics (it’s more elegant if Cleopatra’s eye shadow doesn’t run, right?) It was also judged an indispensable ingredient of ink, without which the soot or charcoal would sink in water or into the surface of the paper—not bringing a beautiful lustre to your penmanship! According to Tamim ibn al-Mu’izz ibn Badis, who wrote around 1025 a treatise on writing and art materials (maybe the first one?), such an ink would have “the semblance of water that is seen upon a sword”!5 A privilege not available to Oriental calligraphers, somewhat far from the acacia trees of Sudan, who bonded their ink with animal hide glues and found a trick all their own to impart lustre by adding shellac.

Both these traditional methods are still used today to make ink but have often been replaced by an acrylic binder… Cry your eyes out while reading that love letter; it will never ‘dissolve’ as romantically as if written in gum Arabic ink! (Same with these recent additions of acrylic-based gouaches and watercolours that cannot be rewetted… an advantage for some artists and not for others while their colours definitely retain more intensity when dry.)

Gum Arabic remains elusive. For one, it was never from Arabia (only exported via its ports), and for two, it cannot be cultivated or grown since we do not even understand how the Acacia Senegal tree produces gum or where in its organism!

Honey and Waxes

Ink is usually used in quite a concentrated form, whereas watercolours tend to be diluted more, the colours losing some of their brilliance along the way.6 So, if, indeed, you wanted to add a bit more je-ne-sais-quoi to your watercolours, a tad of honey might be just the go-to. It sticks but dissolves in water just like gums, and adding a touch to your solution will bring that extra luminosity. Blockx seems to have been the first manufacturer to do so, but others have followed suit. (If you wanted to DIY, a pale liquid honey seems like a good idea; that’s what they use at Sennelier, I noticed.)

Apart from that use, honey, by itself, doesn’t seem to be used as a binder.

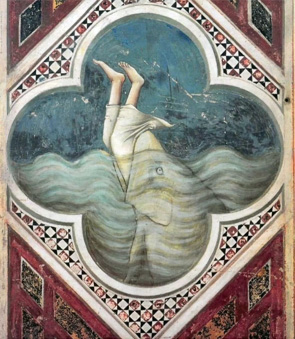

However, another present from the same industrious little one, beeswax, most certainly is. Many drawing materials incorporate wax in their formulations: crayons, oil pastels and some brands of coloured pencils, too. I only know of one line of wax paint that comes out of a tube, however: Ceracolors, a water-soluble beeswax-based that can be used for encaustic and cold wax painting techniques. One does not need heated tools to apply it, yet it can still be manipulated with hot tools once it dries.7 Encaustic, usually, is messier! Even today, with electric hot plates and instruments, it is still a happy, wild affair, but mixing pigments and heated wax (often with the addition of damar resin) and then ‘fusing’ the paint to its support close to a source of heat has been around since the 5th century B.C.E. What they used then to play with this hot paint is a bit of a mystery as few tools or treatises tackle the subject. From the spatula-type tools we have found, it seems artists worked on wood panels vertically, applying the paint with brushes and spatulas and then fusing it by bringing it to a cage mounted on the end of a stick containing hot coals. Why would one take all that trouble, you might ask? Ah, well, there are two (very good) reasons: Opulence and Resilience. (I confess pinching the words below from the R&F website because Richard Frumness’ prose is simply the loveliest of all paintmakers’.)

Opulence. Encaustic is perhaps the most beautiful of all paints, and it is as versatile as any 21st century medium. It can be polished to a high gloss, carved, scraped, layered, collaged, dipped, cast, modeled, sculpted, textured, and combined with oil. It cools immediately, so that there is no drying time, yet it can always be reworked.

Resilience. Wax is its own varnish. Encaustic paintings do not have to be varnished or protected by glass. Beeswax is impervious to moisture, which is one of the major causes of deterioration in a paint film. Wax resists moisture far more than resin varnish or oil. Buffing encaustic will give luster and saturation to color in just the same way resin varnish does.”8

Not all the Fayum portraits, c.1st & 2nd century A.D., make use of the impasto possibilities of wax but, as far as I know, they are the first to do so as, probably thanks to their binder medium, the first able to do so. What they all display, however, is how indeed well preserved they are in their beeswax paint film. Fresh, even, and with that typical luminosity of wax… not quite oil’s, something more subdued, eerie perhaps even, which is wax’s most opulent charm (in my eyes anyway!)

A far more recent ‘paint’ using wax are pigment sticks or oil sticks, as they are both called. These are halfway between a drawing tool and a paint. Better said, perhaps, is that they are an oil paint (linseed oil and pigment) which, thanks to the addition of wax, can be moulded in a stick. Held in hand as a large texta, they are fantastic to draw-paint with, and of course you can mix them with traditional oils. Made of natural beeswax in some brands (a softer stick) and mineral wax in others, they offer a freedom and direct approach to the surface which has no real equivalent… try them if you will; they are messy, and your hands will be sticky, but it’s definitely an… experience!

Finally, wax can also be found in some mediums (cold wax medium, wax paint paste, etc.) and as a final picture varnish.

Egg

“The egg has been with us for so long, it practically hatched us” muses Kapka Kassabova in Elixir.9 Maybe it did indeed, as raw, boiled, fried (sunny side up or down), scrambled, poached, baked, whisked to a frothy cloud (just the white), etc., … egg binds, thickens, coats, serves as a leavening agent, emulsifies and… sticks! (Making it a fabulous binder.) There are probably more ways to accommodate eggs than any other ingredients (potato might be a contender, but I haven’t bothered to fact-check that.) On the other hand, there aren’t that many recipes for paintmaking with eggs, but it turns out there are still quite a few. Tempera paint (as paint using egg as its binder is called) is an emulsion, sometimes using the whole egg, sometimes only the white, only the yolk, sometimes some oil is added, and sometimes it’s even emulsified in beeswax. Over the centuries, many criteria have been found for choosing those eggs over these eggs—with the colour of the shell to the provenance of the chook (country or city seems to have made a significant difference) giving many a fascinating discussion, as you can imagine! Yet freshness seems to be the number one. Freshness of paint, once made, was/is a problematic issue, too. Make too little, and you must repeat the procedure; make too much, and over the next few days, your egg starts to rot and stink… a delight! This being said, tempera is probably the easiest way to make paint in your home (more about that in the Paintmaking section of the book.)

Hides and Bones

The name collagen, from the Greek kólla, ‘glue’, and suffix –gen ‘producing’… tells it all! This glue-producing ‘something’ is mostly found in bones, tendons, cartilage, ligaments and skin (25% to 35% of a mammalian body’s protein content is collagen.) So, not many who roam the earth and the seas don’t have collagen in their structure, including us. Boil away skins or bones and you get gelatine, a translucent, colourless, edible—if flavourless—ingredient. A process understood all over the world way before it got its Greek name, of course. In the wonderful PIGMENT store in Tokyo they offer fifty kinds of animal glues, which is way more than I’ve ever seen before in an art store. My conversation with Dr Kei Iwaizumi, the lab chief with a PhD in… glues, was sadly pretty basic as we shared no common language, so picking his brains was limited. What I did end up understanding, though, is that the glues he recommends for paintmaking are amber-coloured ones. So not the fish glues, which are translucent and the best ones for sizing paper, not the really dark rawhide of deer or donkey ones, which are used in Sume-i ink making but any of the middle tones ones (like our better-known rabbit skin one). There must be nuances to this otherwise why would you need fifty shades of glues but…

In Western stores what you will always find is, indeed, Rabbit Skin Glue, as some artists still traditionally prep their canvases, sizing them first with the glue and then adding some to their genuine gesso. It also is used as a binder in distemper paint, an early form of whitewash. If the name alone breaks your heart, maybe a consolation to you is that it designates a particular concentration of glue and is usually not made from rabbits anymore (still another animal’s gelatine.) Hide glue’s name is also just a different glue concentration, not a specific provenance.

Milk

Ha milk! A whole book could be written about it10, but for our purpose, we are more interested in the coagulated version… a process obtained either naturally (milk sours) or with a bit of help from acidic substances (such as lemon) or from adding a culture. Whichever way you get there, when your milk’s proteins (called casein) curdle into solid blobs, you then have the choice to either make cheese or paint a masterpiece… or, as proof above, both!!

This curd, which we call casein in the paint world, is sticky, and at some stage in history (as said earlier, I’m not quite sure when), we understood it could be a paint binder. It’s a great glue, and later, it was also used to size canvas. Today, casein paints are few and far between on the shelves of an art store. They did have some lovely properties, though (they had the appearance of oils save for drying matt, for example), but when the flexible acrylics hit the stores, their drawbacks (brittleness, not really waterproof, thick applications are not recommended, etc.) were mostly the end of that binder. As far as I know, only a couple of brands still offer limited colour ranges in tubes (Sennelier and Richardson) and some artists do love them, but they hardly fly off the shelves.

Oils

A vast variety of natural oils can be obtained from pressing seeds, nuts, olives, etc. or are even found in weird places like a cod’s liver but only a handful are commonly used as binders in paint. Why? The others never dry. (To be fair, no oil ever dries; it slowly oxidises, some faster than others, and these, which we use, are often grouped under the annoying/incorrect label of drying oils.)

Eventually, and most presumably after having tried everything that grows under the sun, painters and, later, paintmakers, have stuck with linseed, poppyseed, walnut and, more recently, safflower oil. The overall favourite is linseed, obtained from the seeds of a plant belonging to the Linaceae family (Linum usitatissimum), and we’ve quite inventive with variations of that product. It can be used raw, and the golden cold-pressed extraction is considered the best quality due to its higher linolenic acid content, which improves wettability and dries to a hard, durable film. However, the drying time is particularly effective in boiled linseed oil. In the good old days of The Great Masters, a sun-thickened painting oil was also used as a painting medium, during which a fatty oil (oleum crassum) was formed by the slow absorption of oxygen in sunlight. This gave the painter a fantastic tool to move the paint around and yet still ‘dried’ relatively fast. (They were obviously just as impatient back then as we are now!) Linseed Stand Oil, on the other hand, is heated without oxygen. The process prevents oxidation yet produces a slower-drying oil. One, however, that is very weather-resistant and dries to a pleasant gloss. Refined Linseed oil (not often called Alkali-Refined Linseed, as it should be) is a more recent addition to the options in which the oil is extracted from the flax seed using solvents and a steam-heated pressing method, then treated with alkalis and washed in water to remove the precipitated salts.

Apart from drying time, another concern of linseed oil is that it yellows with age (Stand Oil somewhat less). To limit that adverse effect, slow-drying walnut oil was also used, sometimes only in the lighter parts of a painting. Today, many paintmakers use poppyseed, safflower or walnut oil for the lighter pigments (whites and yellows), where the yellowing might be more noticeable, but still linseed for all other colours (it’s a bit cheaper and won’t be noticeable). However, all these other oils don’t produce as strong a paint film as linseed, which transforms into linoxin during oxidisation, giving the pigment-binder structure more stability and strength.

Castor oil? Yep, that one was used too. Bocour, the company that later turned into Golden, survived the war—lean years with virtually no materials and no one playing with them—thanks to the new “Paint-by-Number” craze that hit the country early in the 50s! By then, Leonard’s cousin, Sam Golden, was fully on board as a paint maker, and he devised this oil paint based on castor oil that would stay wet in very small plastic pots. This minor achievement (produced by the tens of thousands of little pots per day) finally allowed Leonard and Sam Golden to buy real mixing and milling equipment for their factory. Apart from that success story, I know not of castor oil used in paintmaking anymore!

Natural Resins

Natural resins—soluble in numerous organic liquids but not in water—such as amber, copal, dammar, mastic, Venice turpentine and shellac, are still used in today’s paint world. Most of these are extracted from plants such as pine, spruce, cedar, and juniper, save for shellac secreted by a female bug. Shellac is the binder of Indian ink; you can also make a fixative for your pastels and other drawings with it, and it is used as a varnish but mainly for precious furniture or violins. (Outside of the studio, it has many other surprising uses, however, from the coating of jelly beans and Braille sheets to the making of ballet dancers’ pointe shoes or even, until vinyl came along, gramophone records… check it out, it’s a fabulous material.)

All the others are not binders, per se, but used in conjunction with other binders to harden them (e.g. Dammar in wax) and, to my knowledge, only one line of paints uses Dammar, Schmincke’s Mussini, combining natural oils such as linseed, safflower or walnut oil with the dissolved resin.

Most resins are used to produce varnishes or as mediums in the oil painting process. Some give body to the paint (copal and Venice turpentine), and all dry fast, so are perfect glazing mediums, especially Dammar, by itself, combined with a drying oil or in a 50/50 mastic/Dammar medium. The semi-precious amber offered until recently only by Blockx… seems to have vanished from their catalogue, which is a shame as it was a luscious medium, if expensive, and spared you the varnishing process, but… I get it!

Synthetic resins

“Synthetic resins used as adhesives provide a wider range of properties than natural-based adhesives. Examples are 1) Thermoplastic resins: Cellulose nitrate, Polyvinyl acetate, Ethylene vinyl acetate copolymer, Polyethylene, Polypropylene, polyamides, polyesters, acrylics, and cyanoacrylics. 2) Thermoset resins: phenol formaldehyde, urea formaldehyde, unsaturated polyesters, epoxies and polyurethanes. 3) Elastomers: natural rubber, Butyl rubber, Polybutadiene, Styrene-butadienne rubber, Nitrile rubber, silicone and Neoprene.”11

Ha, the wonderful (and terrifying) world of plastics! Right. Breathe. Admit. Yes, I researched as best I could. Yes, above is a Wiki definition. Obviously, a list like that also tests not only the limits of my knowledge but also my possible understanding. I recognise certain words from labels on varnishes (and acrylics are part of the list) but, but, but… I am no chemist, and I don’t speak that language—it seems to be English, but I wouldn’t know. So please, if you’re chemically inclined, do your research because all I can tell you is that, yes, many, if not most, varnishes today use synthetic resins but which and why those rather than these and what’s the difference between them… I would rather not say since I will probably make a fool of myself.12

However, if that helps with your total disappointment in me at this stage, I can tell you a little story about one specific synthetic fixative resin, a polyvinyl acetate developed in the 1950s by the French pharmaceutical company Rhône-Poulenc, called Rhodopas M60A and how it was used as a binder. At that time, the artist Yves Klein was desperate to find a binder that wouldn’t alter the raw pigments’ intense gorgeousness when mixed—a consequence of how the light gets transmitted and refracted (much more about that soon.) To his end, Klein collaborated with Edouard Adam, a Parisian chemical manufacturer and retailer of artists’ materials, to develop a recipe for binding ultramarine (he was pretty obsessed with blue) in this Rhodopas M60A resin. Thinned and mixed with other solvents, eventually… it worked! The paint would keep the chromatic strength of the pigment and give the surface an ultra-matt, vibrant texture (yet the binder is not the only reason it worked… more on that later.)

That one is a bit of a one-off synthetic resin used as a binder (I know of no other pigment used with this binder), but IF you bothered to read the above synthetic resin list, you’ll see PVA and acrylics in there, also Polyvinyl acetate and polyesters. All synthetic resins. (Not in the way Dammar is a resin: “Synthetic resins comprise a large class of synthetic products that have some of the physical properties of natural resins but are different chemically. Synthetic resins are not clearly differentiated from plastics.”13) Yet, it seems, for lack of a new and perhaps better word, the term now applies to a wide variety of synthetic adhesives, so must be accepted. How annoying! Nevertheless… onwards to the most important synthetic resin paints.

Acrylic paints are known as polymer emulsions, and so they are, as their binder combines acrylic resin particles and water in an emulsion. The water prevents the acrylic resin from drying and hardening immediately. And, in the case of vinyl paint, vinyl resin and acetate make the emulsion even harder.

It all began when PVA, aka polyvinyl acetate, aka your happy school glue, was invented! Acrylics being so quintessentially American, you might think that it began in the US of A, but in fact, no, a bit further south in Mexico and, prior to that, in Germany (PVA was discovered in 1924 by German Nobel Laureate Dr. Hermann Staudinger). Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, and José Clemente Orozco were the first to soon after experiment with turning PVA into acrylic paint in their monumental paintings indoors and on the facades of buildings. Why? Because our happy school glue seemed to super-stick and… endure! Lo and behold, the first acrylic paint, diluting solid polymer resins with solvents, gave birth to the first acrylic paint co. Politec Acrylic Artists’ Colors, in Mexico in 1953. Yet the recipe using organic solvents did not, in fact, stand the test of time, so more research was needed.

I am not familiar with the process the Liquitex company went through to get there (they were the first to produce a good acrylic paint) but heard a lot about the Golden issues to create this fantastic new product, comparable to no pre-existing one. If you want to read the whole story go to my blog.

The reason they all struggled to try and perfect this? Polymer emulsions are simply the most durable and flexible paint binders ever. (Check out the knot above, which I made just with paint binder at Golden a decade ago and… you can still twist it!) For obvious reasons, as in old age, flexibility in paint is the quality you strive for. It is also an easy paint to use; it needs no solvent, dries quickly, and colours maintain their high chroma. Just add water (not too much), and off you go. Later, it was eventually reformulated in fluid and high flow ranges, and—beyond the usual extender or retarder (opposite issue to oils!)—myriad mediums offer the most extensive range of options any paint has.

Less well known, is another ‘plastic’ paint I have a soft spot for (as I used to play with it when I was a kid… a looooong time ago). It’s a vinyl resin in emulsion paint that combines the velvety mattness and opacity of gouache with the durability of an acrylic. Vinyl is even more adherent than acrylic so you can use it directly on all non-greasy surfaces. Flashe is its well deserved name, as it comes in a really unique range of colours, and to my knowledge, it’s also the only vinyl art paint around.

Finally, alkyd resin, a synthetic resin binder, is now added to traditional oil in some paint ranges. As these “oil paints” dry much faster, impasto or glazing can be done in a single session—which is why you also come across alkyd resin in oil mediums such as Liquin, Galkyd gels and many others.14

That’s it for binders for now, but do not worry; we shall tackle later the two questions now uppermost in your mind surely: “Do binders affect our perception of pigments?” (spoiler alert… they do!) and “How do pigments behave in different binders?” some don’t (behave, that is, but then they rarely all do!) So, many more fascinating tech answers are coming, but now I need to introduce you to the one who will always steal the show in any pigment-binder duo-tango, the colour partner… naturally! (Brace yourselves for the long haul!)

Jump to the next section of the book by clicking here

Alternatively click on the Table of Contents to browse the sections.

You can also subscribe to my blog at the bottom of this page,

and you’ll receive Hues in Tubes in your inbox… as it gets published!

Additional information & references

- Saitzyk. S. ( 1987) Art Hardware: The Definitive Guide to Artists’ Material, p.32 revised 1998 [Online]. [Accessed 13 November 2024]. Available at: http://www.trueart.info/ ↩︎

- At some stage in your painting life, indeed, you will need to understand how to turn your greasy dead bird into an exquisite diner, but I will not go into painting mediums in this book because there are just too many (virtually all good paint companies make some AND give you extensive knowledge of the very diverse options they offer. ↩︎

- This distinction is not always used and some art books and suppliers do call mediums, including binder mediums, vehicles. I chose, here, to employ ‘vehicle’ for non-adhesive liquids that perhaps dissolve some of your material and take it for a ride but do not bind and stick. I will use the term ‘binder medium’ for the ingredient(s) in your paint that do the trick of coating the pigments and ensuring they adhere to your surface. And, finally, when referring to ‘mediums’, I mean the recipes of two or more ingredients an artist uses to move around the paint or alter its consistency, drying time, etc. ↩︎

- van Dalen, D. (2019) Gum Arabic, The Golden Tears of the Acacia Tree, p9. Leiden, Leiden University Press. Definitely a good read in its entirety if the subject excites you. ↩︎

- ibid, p14 ↩︎

- I’m not sure diluted is the exact word, but hopefully, you’ll understand what I mean. There are other reasons for that loss of brilliance we will get into later. ↩︎

- If you think this might be the right paint for you, you can watch a presentation video [Online]. [Accessed 13 November 2024]. Available at: https://www.naturalpigments.com/paints.html ↩︎

- [Online]. [Accessed 13 November 2024]. Available at: https://www.rfpaints.com/encaustic) ↩︎

- Kassabova K., ((2023) Elixir, In the Valley of the End of Time, p. 202. Jonathan Cape, London. ↩︎

- I don’t know of a book but Melanie Jackson actually made a really interesting film about milk. If you care to see it go to: https://www.weareprimary.org/projects-archive/melanie-jackson-deeper-in-the-pyramid ↩︎

- [Online]. [Accessed 13 November 2024]. https://cameo.mfa.org/wiki/Synthetic_adhesive ↩︎

- I am glad to report I am not the only writer on art materials who found this an impossible task. Hear this from Kaye Reed, author of The Painters Guide to Studio Methods and Materials, 1983. Englewood Cliffs, Prentice-Hall, Inc., NJ, U.S.A. “Within each large group of synthetic resins [acrylic, alkyd, polyvinyl, styrene] there exist literally dozens of specific resin products, each produced in many grades, each manufactured to have different viscosity, adhesive properties, color stability, toxicity, and acidity, among other variable characteristics. Then, for each resin, there are many auxiliary solvents, plasticizers, retarders, and other modifying agents, each of which is likely to affect the binder, the pigments, and the brushing and storaging quality of the paint. In many cases because the ingredients are poisonous or highly flammable, they require safety measures which are well known to industrial users but not to artists. Research in this field is often easier for the manufacturers of artists’ materials and their staffs of chemists and technicians.” Pffuuu… I’m not alone! ↩︎

- [Online]. [Accessed 13 November 2024]. https://www.britannica.com/science/resin ↩︎

- If you might have an interest in an alkyd paint vs a traditional oil, maybe go to this site for a comprehensive review of the advantages and disadvantages of one over the other. [Online]. [Accessed 13 November 2024]. https://jonathan-brier.com/alkyd-oil-paints/ Also this good article https://paintingbestpractices.com/alkyd-vs-oil-paints-differences-and-best-practices/ ↩︎

Discover more from in bed with mona lisa

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Sabine….wonderful! I’m going to share this with my painting students!

Love, Ed

I will be honoured… thanks for doing so (that’s the whole point of putting it online and for free!) xox Sabine