WHEN?

PIgments in History

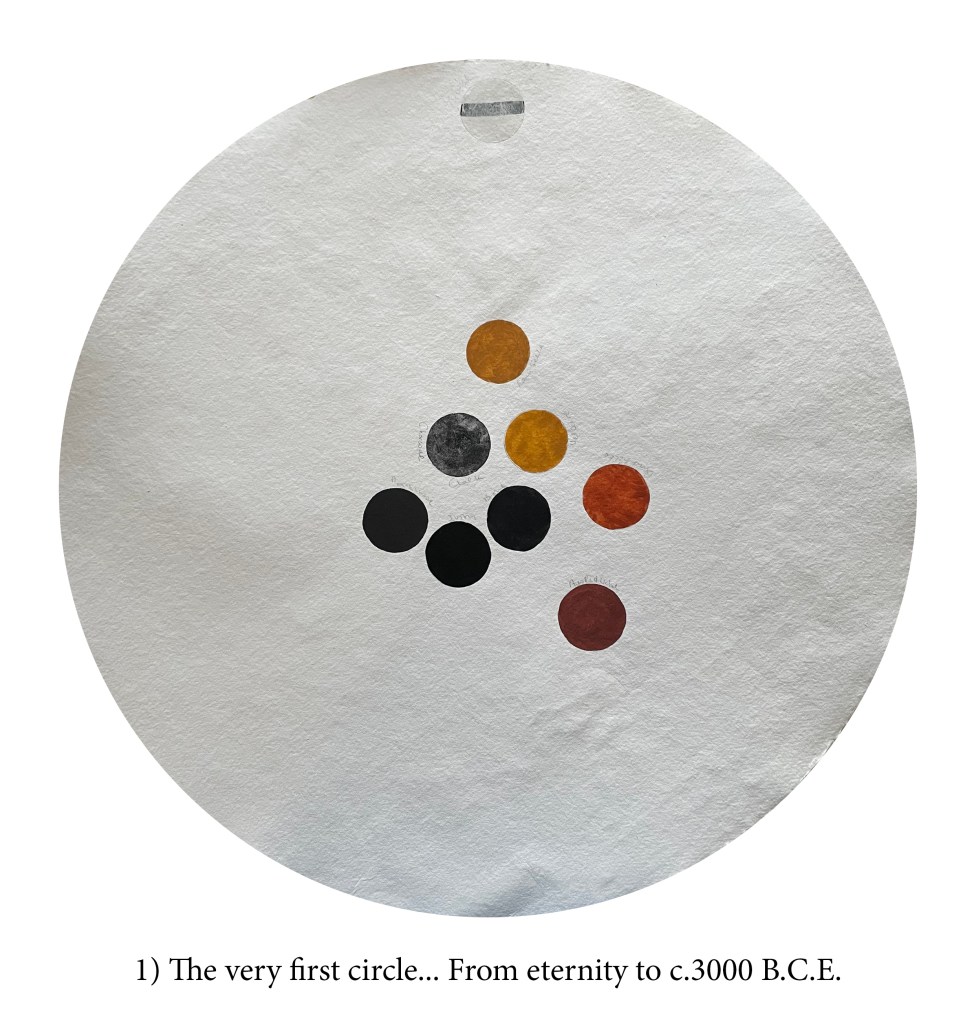

The very first circle

A timeline of pigments, such as the elegant one produced by Vivien Martineau here, should, in truth, begin like hers million upon million of years ago, in deep, deep time. My timeline unfolds from when those I have termed Art Pigments arrived in human hands. However, I am well aware that art is a lazy term, fraught at the best of times, and even more so probably when describing these first tens of thousands of years. Intentional marks, for sure. Created in contexts we cannot fathom, yet I doubt there is the slightest chance those who made them thought they were making ‘Art’—even if they sometimes applied themselves to producing extremely beautiful works.

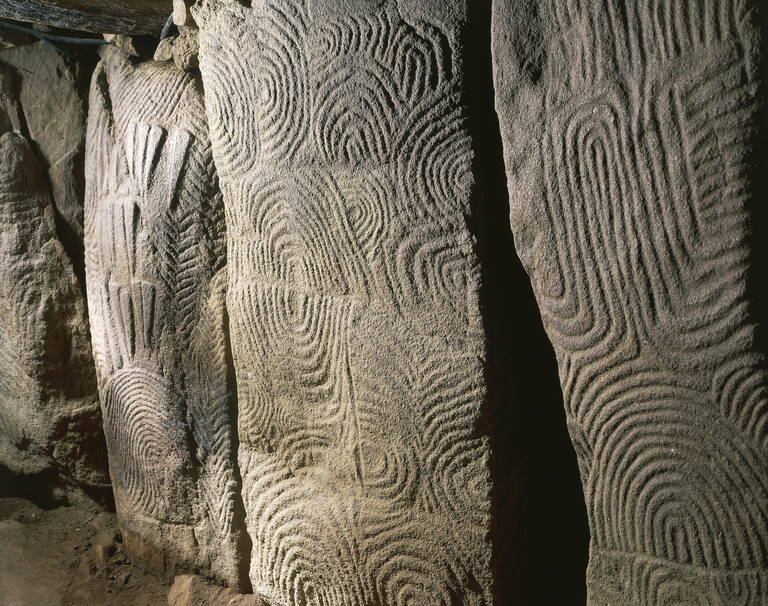

The Blombos cave’s raw pastels perhaps display our oldest marks (for now), but over time, and it seems the world over, more shapes appeared—circles, dots, wheels, arrows, spirals, infinity loops—and, eventually, these early pictograms became more sophisticated ones, iconic images we can understand better as they seem so symbolic to us: hands, beasts, hunts… These early mythopoetic doodles—necessary to us it appears, as they are replicated everywhere—usually do not represent some ‘thing’ we can so easily read. Nevertheless, I cannot help but muse these early marks could be the premises of written language, a shorthand for stories, an ever-growing abstract lexicon which, in time, turned into letters and characters, combining ad infinitum our narratives and dreams.

An early palette would have looked somewhat like Vivien’s geological one: mainly subdued earthy colours, complemented by the whites of calcium carbonates, chalk and charred blacks of all ilk. These were in resonance with the natural world, in which high chroma colours are few and far between. Nothing much has changed today, and every time my eyes are attracted to a little bit of vivid blue or ultra-bright yellow in nature, it’s usually, to my despair, a half-buried wrapper or a bottle top rather than any natural occurrence… and one more dirty thing in my pocket for the whole walk! It’s not that bright blues or yellows don’t exist in the natural world; it’s just that they are indeed rare and usually perched on a branch or attached to the branch rather than on the ground. Yet soil is not dull, far from it! But occurrences of intensely coloured earths are rare and always were precious. (Traces have been found of foraging for red ochre in the most back-breaking places, such as the Subterranean caves of the Yucatan peninsula or at the top of mountains in the Highveld of Eswatini.3)

Many animals change their body colour, using their altered egos to seduce, camouflage or deter depending on circumstances. Surely us, humans, did too, and for the same reasons. Yet one can safely venture that our ancestors went a few steps further and discovered some of ochre’s medicinal (when ingested) and siccative (most useful for wounds, corpses, and to preserve hides) properties and how it could be used as skin protection against the sun and mosquitoes, possibly even see it as psychic protection. My hope is that these men and women also had pleasure painting their hair, the bodies of their lovers, of their sons and daughters before initiation, the space on the ground where they held circle and ceremony, and, if those still practising some of these rituals are anything to go by, there is a fair chance pigment was also present back then—even if, as Australia’s First Nations practices today show for example, they would also widely differ from group to group.

Ochres—iron oxides in the browns, yellows, oranges, reds, even violet—and other Earth/Terre/Terra hues available for parietal creators to play with remain useful hues for artists today, yet our attitude towards them Series 1 Earth colours has changed. Dirt, as it’s even called, says it all about how some see Earth—a shift probably needed so we could exploit her bounty shamelessly, as we do. The mining of ochres, understood by some as “our co-evolutionary partners,” sadly mirrors how we treat our planet. In lieu of what was once sacred, expressions of the revered Gaia, Ceres, Demeter, of the potent Mother’s “womb” and “tomb” of all material things, we see an indifferent matter, worthless dust. I would encourage you to take another look…

Personally, I am extremely moved by these pigments. I enjoy their company on my shelves and cannot have enough earth tones in my toolbox. In reverence of their ongoing power as well as a gesture of goodwill to shells, I perhaps belittled earlier on, I painted one (of sorts!) with all the 33 earth pigments in my possession that day. This hommage is a contemporary one, however, as at my disposal were Ochres and Earths from England, Italy, Cyprus, the United States, France, Germany and Australia—a range never available in times past to any painter evidently. Nevertheless, people all over the planet and from prehistoric times have used these… somewhere.

One of the very first colour tricks we learned was to ‘roast’ our ochres under our fire pits. Unchanged from around the Middle Palaeolithic, when it is believed we understood how to do this, the air-free process alters Yellow Ochre by eliminating the water content in it and offers precious variations of orange and, especially, red tones. The practice, it seems, was performed even in places where Red Ochre was, in fact, available, and so could have had more spiritual than chromatic motives, but there is no evidence either way. The huge ovens in the ochre processing plant of Roussillon are reddened forever by this operation, so the practice not only continued but was extended later to Earth Siennas and Umbers (as you can see in the entrance of the Blockx paint-making factory, where you can still notice the little ovens.) However, no paintmaker I know of does his own roasting today.

Not all pigments change colour under fire either. Once our barn in Provence was caught in a tremendous fire that burnt all the trees and bushes around us to the ground. We had evacuated, of course, but the next day, could not believe our eyes. The house was standing, the horse and donkey too in the middle of their field, but the large corrugated iron shed had simply dissolved! Gone everything, including all of my mother’s possessions. She was moving to the area a few weeks later and had forwarded her furniture, books, etc. Weirdly a couple of ceramic vases were standing (triple cooked yet fused to the cement floor!), but even the cast iron radiators had melted to a puddle while all the rest had simply disappeared as if it had never existed. That’s when I remembered all my father-in-law’s paintings had been stacked against the back wall. They, too, evaporated, of course. The canvases, the wooden boards he favoured, gone up in smoke and, in their stead, beautiful little lines of coloured rocks on the ground. A little bit of yellow, of red but mostly blue, all his beautiful blues… Yep, pigments can make you cry, too.

This early palette lasted for millennia. Not that ochres and minerals can be dated, and we have had some surprises too, such as the already mentioned Manganese Black on the snout of the auroch in the main Lascaux cave, a pigment not so readily available. One day soon, we might know for sure its origin nonetheless because, if we can’t certify dates, we are now beginning to be able to track ochres geographically. The people behind this forensic archeological scene, researchers from Flinders University in Australia, are using microbial DNA profiling to identify which impurities and trace elements are present and in what amounts to accurately locate back to their sources the ochres used on Aboriginal artefacts. We know that indigenous people travelled around the Australian continent for centuries and that ochres were exchanged and offered, but this microbial information, if matching the data of a known geological site, will become a precise signature for the specific soil in which it was collected. Fascinating, isn’t it? Over the centuries, pigments’ roamings on the planet are fairly well documented, but I am not so sure ochres originally went ‘walkabout’ elsewhere as much. Melonie Ancheta, who researches the use of Vivianite along the Northern Northwest coast of the American continent, seems to think not:

“Like with all other resources, pigment deposits would have been “owned” by a family or clan and they would have had direct relationships with the places at which pigments were locally available. Landscapes were often imbued with some kind of importance which made, in turn, the pigments particularly special. Sourcing materials from distant regions or through trade would decrease the significance of those materials and reduce the likelihood for use on ceremonial or spiritual objects.”4

Ochres, these fragments of place, relate more strongly to us if that place is ‘ours’ it seems… it seems they might even define us. Hear the Himba women—known for smearing their bodies red and matting their hair into braids with the same mixture of animal fat, ash and ground ochre—justify this ancestral daily ritual: “It is our culture and our tradition. It makes us look and feel beautiful. And all can see that we are real Himba women. There are no Himba women who are not red. They do not exist.”5

Would you be interested in having a look at

and read a little story about the seven pigments in my first circle?

Click here

Jump to the next section of the book by clicking here

Alternatively click on the Table of Contents to browse the sections.

You can also subscribe to my blog at the bottom of this page,

and you’ll receive Hues in Tubes in your inbox… as it gets published!

Additional information & references

- Available for purchase at: https://www.vmartineau.com/ ↩︎

- [Accessed 29 December 2024] Available at: https://www.liberation.fr/sciences/archeologie/sixtine-du-neolithique-les-lignes-du-cairn-de-gavrinis-entre-interpretations-et-archeologie-20241227_WLZBKX7ODZDRBKM2L2CHIHNEX4/) ↩︎

- MacDonald B.L. (2024) Global Insights into Ancient Ochre Mining. Pigments Revealed International Talk. Available at: https://www.pigmentsrevealed.com/member-videos (It’s member access only, but you might consider becoming a member! It’s truly a wonderful non-profit sharing so much about pigments.) ↩︎

- Ancheta, M. (2019) Revealing Blue on the Northern Northwest Coast, p.23. American Indian Culture and Research Journal, vol 43, no 1, American Indian Studies Center, UCLA. © Regents of the University of California ↩︎

- Vandyke, I. (2021) My Wanderings with the Himba [Accessed 12 November 2021] Available at: http://ingervandyke.com/2017/03/my-wanderings-with-the-himba/ ↩︎

Discover more from in bed with mona lisa

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.