WHEN?

Pigments in history

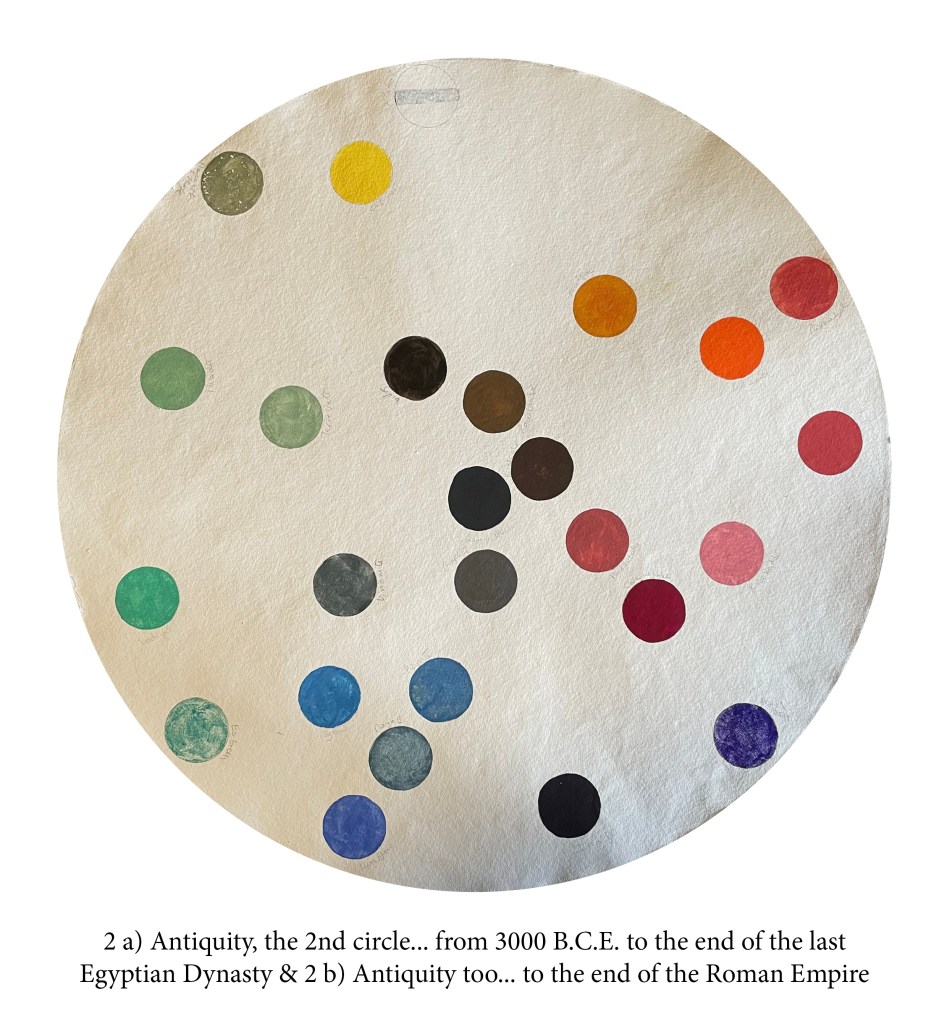

The second circle

a) From 3000 B.C.E. to the end of the last Egyptian Dynasty

Eventually, many centuries + the 3000 years of Egyptian rule later, well… it might seem that not much has changed at first glance! An inspection of the colours available to a pharaoh or his grand vizier shows pigments not that different from those used in cave art worldwide. With the noticeable difference of a green1 and Egypt’s famous blue, the 18th dynasty palette of Amenemope, Amenhotep II’s P.M., offers only a red ochre and two charcoal blacks. While in the ‘watercolour’ pans found in Tutankhamun’s tomb, presumably so he could go on enjoying the pleasure of painting in his afterlife, we find ochres, again Orpiment and the green mineral Malachite.

In fact, besides these, quite a few other pigments were used by Egyptian artists, such as the blue Azurite (a mineral found alongside Malachite), Realgar, another red-orange arsenic sulphide and, possibly as inks, Indigo and Madder.

We will see how precise and complex the making of Egyptian Blue was, but the brilliant chemists of the Egyptian people didn’t stop at that pigment. They also eventually understood how a process could turn their kermes and madder dyes into lakes and usable paints and, around 3500B.C.E., discovered how to win copper from its ores—which opened the door to chemical manufacturing. Lead Antimonate Yellow, a pigment that would return later under the misnomer of Naples Yellow, was also well known to them if only used for glazes and in glass making.

They were probably quite content with these few pigments because, as ever and with everything in Egyptian life, colours were symbolic and limited to a regulated six—an exquisite Natural Colour System2 based on three pairs of elementary colours, mind you (white/black, red/green, yellow/blue)—so no need for much more. You could mix these in profane scenes from daily life but only use them next to one another in funeral and other sacred uses. And indeed, no need to crush the beautiful lapis to turn that precious one into a pigment. Not that they did not import it from Afghanistan nor embed the stone in sculptures, funeral masks, or carve it into amulets, but the gold streaks in lapis (fool’s gold but then…) established a connection for them between the stone and the sun, their highest divinity of course. Newb, gold, represented the flesh of the Gods. To get rid of Ra and turn the rest of the mineral into a blue paint was not a cultural option! (Plus, understanding how to get that celestial blue would take another few centuries.3)

Meanwhile, others over the seas… The time is 1500B.C.E., and via a series of independent cities located along the coast, the thriving island city-state of Tyre trades all over the Mediterranean and beyond. Its people, the “princes of the sea” as the Bible refers to them, not surprisingly perhaps, get from the Greeks, according to Herodotus, another name who jests them the Phoinikes or “purple people”—thanks to their most lucrative trade, a rich purple dye equal to no other at the time… and without competition for centuries to come! Produced one drop at a time with the purpura juices of an interesting little sea snail called murex, Tyrian Purple eventually got its name from the city while staining the skins of its inhabitants indelibly. The nickname stuck too, and in good time, the purple colour of the Tyrian people gave the Phoinikes the name by which we know them today… Phoenicians!

b) Antiquity too… to the end of the Roman Empire

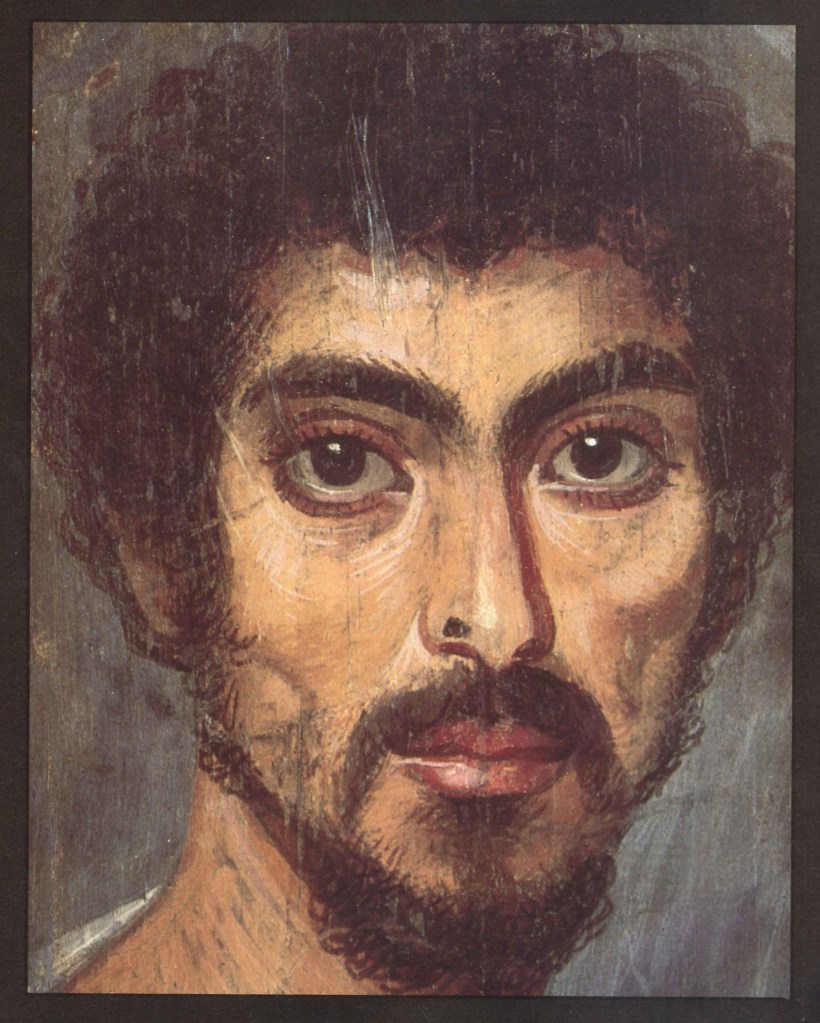

Amazingly enough, by the time Cleopatra—remembered as the colour drama queen par excellence who had already turned Julius Caesar into the first all-purple toga purpurea emperor—appeared to Marcus Antonius on her royal barge draped, as well as her entire retinue and the sails of her boat in the same extravagantly expensive Tyrian Purple to make his conquest (Plutarch only mentions the sails but… that’s already a mighty lot of little murex!) many of the pigments and techniques which would be used for centuries to come had been understood and routinely used by the Egyptians. Their time was over, but by then, the admirable Greek painters were in full swing and, presumably to their delight, the list of colours available to them had somewhat expanded. Ceramics apart, hardly any of their painted works have survived except for the Fayum “Mummy Series”. Produced from c.30B.C.E. to the 3rd century during the Roman rule over Egypt, these are believed to be from the hands of Greek artists, perhaps from the Greek Fayum community itself. The talented painters behind these encaustic and sometimes tempera-on-wood portraits used materials both local and from across the Roman Empire, giving us many precious clues as to their materials.

In the case of the more refined ones, the faces affixed to the coffins were rarely painted on local Egyptian sycomore fig, apparently only good enough for the more basic caskets, but on “imported” boards made of more durable woods from all over Europe: oak, lime, fir, yew, as well as cedar from Lebanon. Painters still used quite a few Earth colours, of course, as well as Madder Lake, Indigo, Chrysocolla, copper-based greens, gold leaf, Egyptian Blue (named Caeruleus by the Romans) with the most useful Lead White, and its fiery counterpart, Red Lead. Bound in a beeswax-based binder, applied with a combination of tool and brush, these ‘face-masks’ display a rich array of colour combinations and variations—perhaps thanks to the binder, coating the pigments in a way no earlier binder had, allowing artists to dare mix those of dangerous company with one another. Over one thousand of these unforgettably striking portraits are still in existence, endowed with life, expressions, and attitude… a far cry from the Pharaonic representations of humankind. In truth, every time I discover a new one, I am moved anew by the freshness and modernity of these Fayum beauties.

The advantage of having an empire, especially one as vast as the Roman one, is that you can grow wheat where it grows best, mine raw materials where there are some, manufacture where it is most convenient and then build beautiful straight roads and strong boats to take all these conveniences where you need them most… all roads leading to Rome, of course! Nevertheless, some obviously also led to Pompeii, another rich city of the empire, delivering not only colouring goods but fashion styles and artists. Enough to justify a pigmentarium, the first recorded art store in the world! There, what has been found under the ashes is of unparalleled importance to us. We can analyse the artworks anywhere, of course, but we can only see a store’s wares as they were at the time in Pompeii. Elsewhere, too, a group of painters abandoned the tools of their trade: paint pots, mixing bowls and compasses, as they fled from a villa in the doomed year of A.D.79. There is also a very useful inscription in Charcoal, which has helped historians set a new date for the eruption (more about that later… can’t tell you all my good Pompeii stories at once!)

So, which pigments were available to these artists? In the reds, you could find Cinnabar (natural Vermillion, which probably came from the Almadén Caves in Spain), Sinopia (the best ochre from Sinop in Turkey, a Greek colony on the Black Sea ), Hematite in various tones and some burnt Yellow Ochre. In the yellows, more ochres, of course (Limonite and Goethite), a reddish yellow pigment resulting from the calcination of Litharge—which also goes under the name of Massicot—while Minium/Red Lead would have contributed a purer orange.

The green palette consisted of Malachite, Green Earth (from either Verona or Cyprus) and Egyptian Green, presumably produced along Egyptian Blue/frit/Caeruleus in Puteoli. That synthetic pigment was, if not mass-produced, still manufactured in four different locations in the empire to answer the need for blue skies… everywhere, I suppose. The closest source from Pompeii was Puteoli (now Pozzuoli), a town close to Naples, whose name comes from putèoli, “little wells” in Latin, referring to the many sulphur fumaroles in the area. (I read somewhere that its modern name could come from puzzare, to “stink”, as the smell of sulphur, still today is quite intense there.) If you dismiss the smell, you have to give the town that it manufactured the highest quality of Egyptian Blue in Roman times, so much so that theirs was given the special name of Alexandrian Blue. The browns also seem to result from Litharge calcination at very high temperatures or mixes of Ocre, Hematite, and Charcoal, while blacks were charcoaled powders from mixed vegetal sources.

But that’s not all you could find in The Antique Art Store… Did you notice that a few years ago, paintmakers began adding to their ranges some pale blues, oranges, greens, and pinks? (Which, quite frankly, left us retailers a bit sceptical.) What was wrong with adding white to all the above colours to get the same result? Well, for one—and possibly only valid reason—consistency! And as unbelievable as it seems, that same reason might have prevailed back then, as the pigmentarium also sold some of these ready-made mixes! You could get them in three pale colours: pink, blue and purple (and this purpurissum, must have been a welcomed alternative to the real and highly dear Tyrian Purple), while the whites in the mixes varied: Asbestite, Dolomite, Chalk, or sometimes Smithite.4 This said, Roman artists, expert at extending expensive pigments by mixing them with cheaper ones, were also adept at mixing colours to produce secondary and tertiary colours.5

By the end of the Roman period, the idea that art for its own sake was a valid pursuit and that supporting and sponsoring artists was not only cool but a reflection of one’s cultural sophistication was firmly implanted. Moreover, art was not hidden in palaces or majestic tombs anymore, but could be seen everywhere. It became accessible and eventually popular (in both senses of the word.) This approach would have a lasting effect in the centuries to come…

Would you be interested in having a look at

and read a little story about the twenty-two pigments in my second circle?

Click here

Jump to the next section of the book by clicking here

Alternatively click on the Table of Contents to browse the sections.

You can also subscribe to my blog at the bottom of this page,

and you’ll receive Hues in Tubes in your inbox… as it gets published!

Additional information & references

- A mixture of Yellow Ochre, Orpiment and the same Egyptian Blue ↩︎

- “The Natural Colour System (NCS) is a proprietary perceptual color model. It is based on the color opponency hypothesis of color vision, first proposed by German physiologist Ewald Hering.(Or perhaps by the Egyptians?!!) The current version of the NCS was developed by the Swedish Colour Centre Foundation from 1964 onwards. The NCS states that there are six elementary color percepts of human vision—which might coincide with the psychological primaries—as proposed by the hypothesis of color opponency: white, black, red, yellow, green and blue. In the NCS all six are defined as elementary colors, irreducible qualia, each of which would be impossible to define in terms of the other elementary colors. All other experienced colors are considered composite perceptions, i.e. experiences that can be defined in terms of similarity to the six elementary colors.” [Online]. [Accessed 8 January 2025]. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Natural_Color_System ↩︎

- Gambardella, A. et al. (2020) How did the old masters make ultramarine? University of Amsterdam. [Online]. [Accessed 8 January 2025]. Available at: https://phys.org/news/2020-05-masters-ultramarine.html ↩︎

- Documentation on Pompeii abounds and is easily found online. Less so, strictly about pigments and paints, but I found these valuable and interesting, so share them with you if you want to read more.

Kapetanidis, N. Les Peintures de Pompeii [Accessed 8 January 2025]. Available at: http://www.vesuvioweb.com/it/wp-content/uploads/Kapetanidis-Niko-LES-PEINTURES-DE-POMPEII.pdf

Roman commerce in pigments [Accessed 8 January 2025]. Available at: https://edu.rsc.org/resources/roman-commerce-in-pigments/1959.article

The Temple of Venus (Pompeii): a study of the pigments and painting techniques [Accessed 8 January 2025]. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0305440311001816

Process: Materials and Making, Uncovering the painters’ methods, tools and pigments. [Accessed 8 January 2025]. Available at: https://www.pompeiiincolor.com/theme/process-materials-and-making ↩︎ - Archaeologists Uncover Rare Blue Frescoes of an Ancient Sanctuary and Servant Quarters in Pompeii. [Accessed 8 January 2025]. Available at: https://www.thisiscolossal.com/2024/06/pompeii-blue-frescoes/ ↩︎

Discover more from in bed with mona lisa

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.