WHEN?

Pigments in History

The third circle

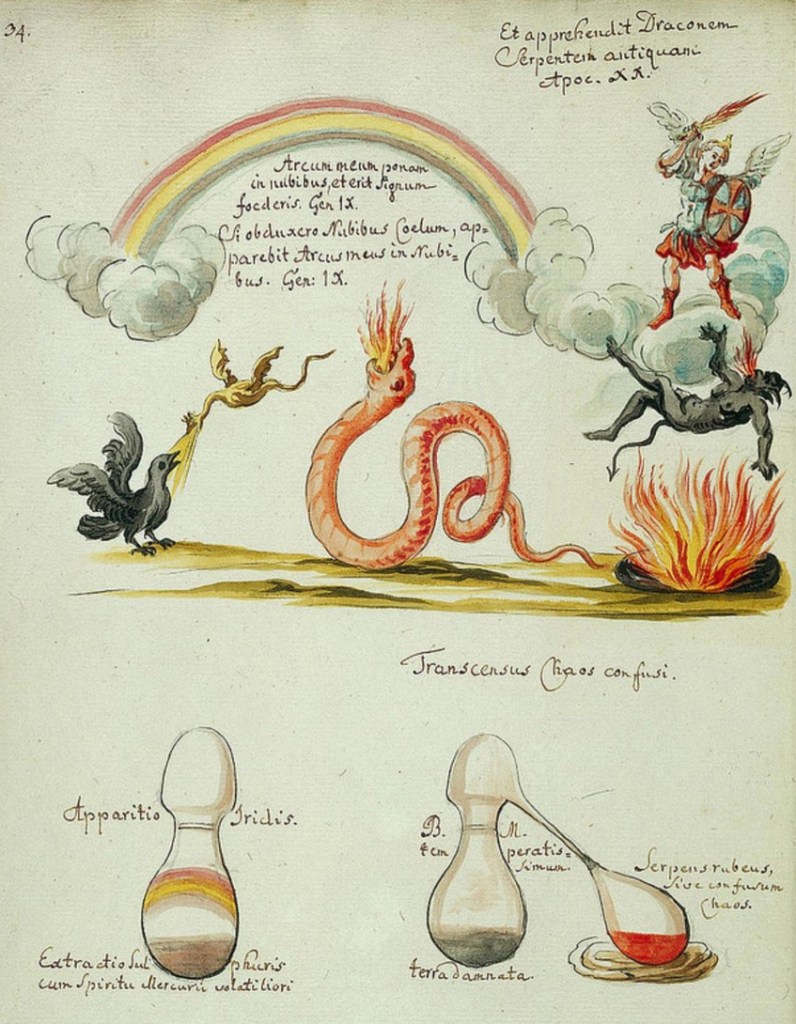

Some would argue that the innovation most critical to medieval painting in Europe was the synthesis of Vermillion—a truly alchemical affair! Imagine combining mercury and sulphur to create a black form of mercury sulphide, which, once pulverised and sublimated by intense heating, turns into a divine red that could be sold for its weight in gold… you might even believe you’ve found the philosophical stone itself! Apparently, the finer you ground this black, the more powerful the red would become; how entrancing.

In the Far East, Cinnabar, natural Vermillion, had been on artists’ palettes since the Neolithic, so that, most probably, Vermillion was first produced there too, long before it was understood in Europe how to make it—and then probably only thanks to the brilliant Arabic alchemist Jābir ibn Hayyān (although his existence is still debated and his name perhaps a pseudonym used by an anonymous school of Shiite alchemists writing in the late 9th and early 10th centuries.)

Today the name Vermillion remains, but what’s in your tube is not the toxic red of old. Red could be debated, too, as the size of genuine Vermillion’s particles is particularly important vs its hue—a range from an orange to a dark red—which is why Cennino Cennini, artist and author of the Renaissance artists’ bible The Craftsman’s Handbook even suggested that “were you to grind it every day, even for 20 years, it would keep getting better and more perfect.”1 (I’ve also noticed in old phials of genuine Vermillion that, probably due to the mercury component, it has a tendency to go on shifting!) Keith Edwards, pigment maker extraordinaire who produces many of the historical pigments for Cornelissen, apparently finds the mercury he needs in old thermometers and barometers. Still, I wouldn’t recommend you give it a go at home!

The pigment became an instant hit, yet it was used sparingly until more sophisticated forms of manufacture, the less laborious wet process with ammonium, rather than the so-called Dutch dry method described above, made it affordable. “If the Middle Ages had not had this brilliant red, they could hardly have developed the standards of colouring which they upheld; and there would have been less use for the inventions of the other brilliant colours which came on the scene in and after the twelfth century.” reckons art historian Daniel Thompson.

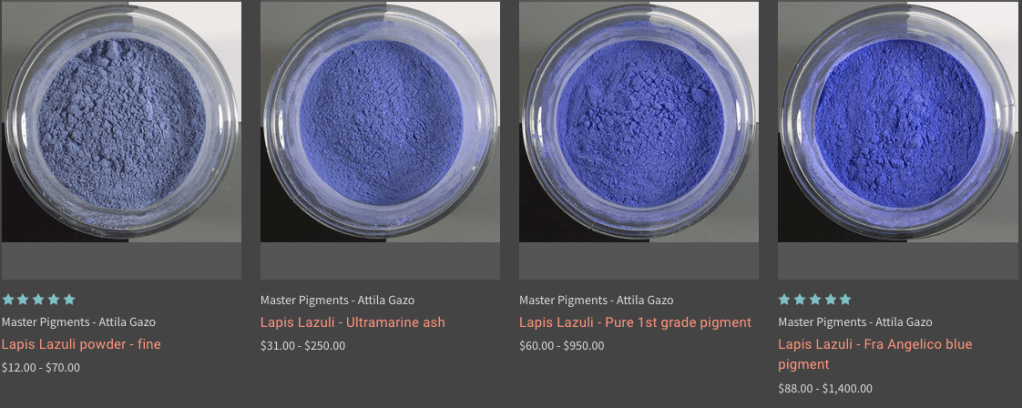

And, in competition for a brilliant colour of the times, one must most certainly now mention Lapis Lazuli, aka Ultramarine genuine, as just as important a pigment—when finally we understood the unusual process needed to turn the stone into a delectable blue, as simple grinding delivers only a pale dull one, as can be witnessed in Afghanistan’s 6th century Bamiyan caves on the Silk Road (its first occurrence but not as the blue we came to adore!) To extract the celestial hue from lazurite, it must first be separated from the other minerals surrounding it: calcite, sodalite, pyrite, etc. Crushed to gravel, then ground and further milled in water to a fine powder, the pigment is now ready to be dispersed into a hot bath of melted beeswax, gum rosin and mastic. The heavy blue sauce is then poured onto a non-stick surface where it can cool until it is set enough to be kneaded thoroughly and shaped into little loaves, oops, sorry, today they are called extraction sticks. These will be left to harden for a few days, then, warmed up in water, the kneading process will be repeated. Pulled and stretched into long flexible strips, the pigment paste reminds me at this stage of the colourful sugary drippings in fairs from which they make berlingots in France, these variegated, pyramid-shaped, irresistibly beautiful and utterly tasteless rock candies. But back to business as extraction can now begin: a most tedious process of twisting, squeezing and playing with the dough in a container of water treated with soda ash which will, in due time (around four hours!), deliver the powerful blue. What is happening is a release of the pigment from the blob you are kneading, which retains all the impurities. Eventually, the particles at the bottom of the recipient will be sieved and then are ready to use. Repeat the process, and you get 2nd rate Lapis, 3rd rate… and finally, Blue Ash, a pale ghost of the precious blue. Certainly not quality Ultramarine anymore, yet painters used all stages of release as ready-made blue variations. (Check out the price difference between them though!)

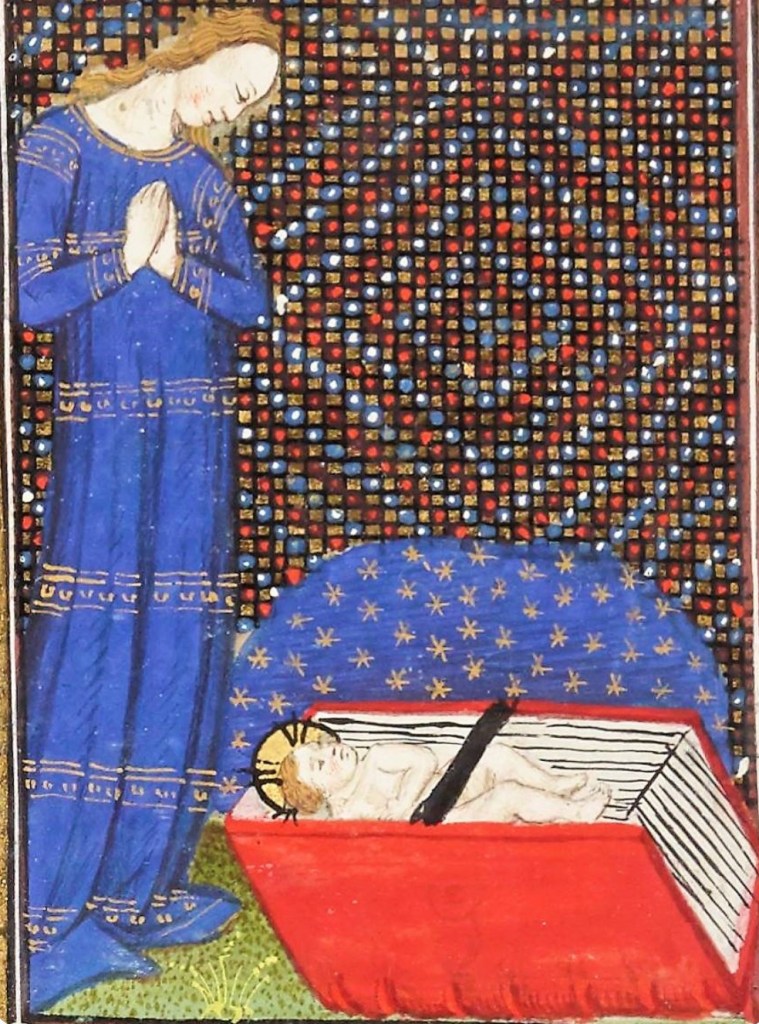

Blue, which had been all but ignored for centuries, suddenly crashed onto the colour stage around the 11th century, the overnight favourite it was destined to become. (And earlier than we previously thought.2) Around then, the stained glass windows of cathedrals suddenly offered a new bold blue thanks to cobalt, the making of an intense blue from Lapis was understood, and, more importantly, woad dyeing techniques improved so that suddenly wearing blue became not only a possibility but a pleasant and interesting new one (as opposed to the previous greyish, blackish blues.) Alternatively, maybe it was answering the demand for blue clothes, which prompted improved techniques, and once everyone started wearing blue, the least a Madonna could do was follow suit… which made producing a superior blue pigment to paint her all the more desperate to find. Who knows? No one really but blue was there to stay, becoming the attribute of the kings of France—soon followed by other royals—and pretty much all of us these days in corporate suits or jeans!

What is certain, too, is that medieval European times saw the recognition and importance of colours change in a way they hadn’t since the beginning of times, from the eternal trio of black-red-white to a suite of six colours with the addition of yellow, green and blue. In this new pecking order, blue and red became the regal opposite pair and would remain the complementary two until other laws decided… it had to be green!

Still, Ultramarine and Vermillion were the two champion pigments of the times, and, truth is, they both go so very well with gold. In scriptoriums all over Europe, illustrators couldn’t lavish enough of the three in their Bibles, while on the other side of the Mediterranean sea, miniature artists depicting the mythic adventures of Persia with a plethora of colourful characters on saturated backgrounds were indulging in the same pigments (more often Red Lead than Vermillion, it must be noted.)

Not all patrons were wealthy enough to afford Gold, though; a poor man’s gold, Mosaic Gold, often replaced the brilliant one. That alchemical pigment was produced by the fusion of tin and sublimated sulphur in the presence of mercury but was hardly competition for the real stuff. On the other hand, Mosaic Gold was said to be an aphrodisiac and an essential ingredient in Ayurvedic medicine against impotence. It could “generate semen of high quality”, give great vigour, clear your complexion, be used as a brain tonic, anti-psychotic and last but not least, even cure gonorrhoea! Another source gives it as useful “in most chronic and nervous cases, and particularly convulsions of children.” One can only hope that Mosaic Gold was more efficient in the body than on the palette!

Cheaper substitutes for blue and red were also needed, and, of course, yellow flowers and green grass must be painted too, so what should be used for these? Greens can be mixed, of course, but yellows were just as scarce. Also, strangely, colour mixing was not encouraged or supported by the times—layering was OK, especially coloured glazes to create transparency, slight colour shifts and brilliance.3 When there’s a will but not much else, first, you look around and see what’s available in your surroundings. You remember your hands stained brown from shelling the walnuts in autumn and your children’s mouths from stuffing them with summer berries. You notice the remarkable orange of that fungus growing on the fallen tree. You wonder how to extract those colours, and despite guilds guarding their secrets closely, you have noticed, too, that dyers have improved and diversified their hues thanks to local plants such as weld or woad.

Observational skills and millennia of trial and error have brought us here. Still, to find what in the natural world that surrounds is happy to yield colour must have been quite a process, especially since some recipes for dyes are… to die for! The Egyptians had already understood how to turn a liquid into a solid by precipitating it into an inert material, yet Medieval times truly expanded the list of these laked pigments, and favoured alum—which converts into insoluble white aluminium hydroxide—for the making of lakes. I doubt they knew that, but what they did understand is which dye makes a good pigment. Lichens work, yes, but also shavings of logwood, sappan/brazilwood; barks of black and yellow oak, walnut and apple trees; madder and curcuma roots; lily pollen; cosmos and columbine flowers; buckthorn and honeysuckle berries; the leaves of indigo and woad of course, but also those of elderberry, mulberry and Solanum dulcamara, a woody nightshade; the petals of safflower; the stamens of saffron; the pistils and stamens of the Sophora japonica flower; the grains of the turnsole/sunsikeel seed and the seed-capsule of Gentiana lutea, the great yellow gentian; while the generous weld—the most universally used yellow dye in medieval Europe, also known as ‘fuller’s weed’ or ‘dyer’s weed’—was happy for you to use its flowers, stems and all. Ruskin describes his beloved Gothic architecture as: “[…]an art never perfect, never simply pretty but always strange, bold and rooted in an understanding of nature”, buildings reflecting the workers’ freedom of expression, their “profound sympathy with the fullness and wealth of the material universe.”4 When I came across those lines, they expressed my admiration for Medieval lake pigment makers so well that I had to steal them!

By now, are you dying to know why these are called lakes? Hear the tale of Lac, then. Used as a dye as early as c.1500 B.C.E., it was first imported around 1220 into Europe as a dyestuff by the Catalans and Provençals. Lac (or Lack) could also be turned into a vibrant, transparent, deep red-violet pigment known under Indian Lake or Indian Red—most politically correct as Lac came from India. (It also has no family ties with the Indian Red in your tube, which is usually an Earth pigment.) Co-created with the host tree so that different species of fig trees gave different dyeing reds, it was not understood for a long time that Lac resulted from a sting from a female scale insect and the reaction from the tree. By the time they reached the other side of the world, the clusters of insects and their larvae trapped in the resin that protected them had turned into hard brown lumps and were believed to be some mineral or solidified sap. The insects, which gave the dark red exudation its colour, were harvested with the branch they had colonised, and Lac was often sold thus, in its raw resinous state on twigs, under the name of stick Lac. To complicate matters, however, when the same insect was left to hatch and fly away, only the resin remained on the branch; a blond substance turned into a lacquer known as shellac. But, of course, artists were more interested in the red variety! Most probably again indifferent to its animal origins, Indian Lake, infinitely cheaper than Vermillion, took the art world by storm. So much so that, by the 15th century, it had become Italy’s most-used red lake for easel painting. Eventually, its popularity extended its name to all the other insect-based red lake pigments, such as kermes and cochineal, and then to all pigments produced from a dye.

Would you be interested in having a look at

and read a little story about the twelve pigments in my third circle?

Click here

Jump to the next section of the book by clicking here

Alternatively click on the Table of Contents to browse the sections.

You can also subscribe to my blog at the bottom of this page,

and you’ll receive Hues in Tubes in your inbox… as it gets published!

Additional information & references

- Cennini C., artist and author of the Renaissance artists’ bible Il Libro dell’Arte (1437), translated as The Craftsman’s Handbook by Thompson, D.V. Dover, New York, U.S.A. ↩︎

- Did you ever realise Dentition is such a good friend of Datation? (Ivory is pretty strong stuff and often survives when all or near all is gone, so has secrets to reveal… Hear this lovely story.) Until recently, it was thought genuine Ultramarine was available later in Europe yet the most amazing find—the skeleton of an aged woman in the cemetery of what had obviously been a flourishing nunnery in Germany—forced us recently to revise our datation somewhat. The lady died around 1000-1200AD but left behind the most unusual evidence of what her contemplative life had been all about. Embedded in the dental plaque of her teeth, more than a hundred tiny flecks of the blue pigment told the tale of a paintbrush repeatedly humected and shaped back into the fine point needed for the detailing work and embellishments of manuscripts… a labour of love no doubt!) ↩︎

- Could it also be colour mixing was not encouraged because so many pigments used then were not permanent? Or used with great caution as they would chemically alter other colours when mixed with them? (This would explain why a touch of Arabic gum was often added to the glazes to ‘seal’ the colours…) ↩︎

- As quoted by Fagence Cooper S. (2019) To see clearly; Why Ruskin Matters, p.86&170. Quercus Editions Ltd, London, UK ↩︎

Discover more from in bed with mona lisa

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

I don’t understand what is the difference between the” blocks” so I simply choose the first…

I am always happy to recieve another episode of your book, that is not a book… and I’m still pondering over this issue…and it is interesting because the need to know the answer, explains something of me. I want to categorisize what I’m reading.So it confuses me, the selfconfidence in the way you describe the facts let us believe that you know what you are describing, and I absolutely believe everything, because I love to follow your associations…and at the same time I keep thinking” how does she knows that and where can I find the source”

Hello dear Katinka

I believe the comment box exists at the end of each posts (you have to hover and it appears in the bottom right… not very obvious!) but I did receive your message anyway… As you understood, I do give the references to the quotes or articles I actually use at the bottom of each section. But too, there will be a full bibliography, which I will post shortly (and perhaps enrich as I go) and I apologise for not making it available yet but I want to make it as complete as possible and… it’s a big job. So, apologies, but you will have to trust me a bit longer (trust my research, in truth, as I found all this information in as serious and reliable books as I could find.)