WHEN?

Pigments in History

The fifth circle

“Nothing is perhaps more peculiar than the process by which one obtains Prussian Blue, and it must be owned that, if chance had not taken a hand, a profound theory would be necessary to invent it”

humbly admitted in 1762, the chemist Jean Hellot.1 If we discard then the discovery of Prussian blue, c.1705, as it was something of an accident, certainly from the synthesis of Cobalt Blue by Thénard, a century later, most colours would see the light of day in a lab rather than any chance discovery in nature. One of the first achievements of the so-called long Nineteenth century was the improvement of lake pigments, thanks to the use of metals, and possibly the most instrumental person in helping make madder and other lake colours that didn’t fade over time was George Field (1777-1854), an outstanding colourman and chemist. He found a process to turn the madder extraction not only into a solid pigment—this had been achieved thousands of years earlier— but in one that had longer-lasting colour and… what a colour! In truth, he made a whole range of madder reds from rose to scarlet, crimson, even purple and brown using, instead of alum, other metal salts containing iron, chromium or tin. His Rose Madder Genuine was so beautiful that Winsor & Newton (who bought his ten volumes of notes and experiments on improving pigment quality) still uses Field’s methods to make the pigment today. They tell you a bit about it on their website, but not enough so that you can reproduce it… it’s a well-guarded secret that pink!

The next step was to find out what, in a plant, precisely gives it its colour and manage to extract this element. When Pierre-Jean Robiquet achieved this in 1826, he discovered that madder had not only one but two colourants: purpurin, which would quickly fade, and alizarin. Later the same year, Otto Unverdorben managed to extract from heated indigo another substance he would name aniline, from anil, indigo in Spanish. Research to synthetically reproduce these most important dyeing colours could begin! However, it was trying to synthesise quinine—a most vital drug for malaria—which opened the colour door wide. Perhaps chance rather than experience (he was only 15!) landed in the hands of the young chemist William Perkin towards mid-century, a rich purple with promising possibilities as a dye.

But he most certainly recognised those immediately, and aniline purple, mauveine, was an instant hit. Fuchsin came next, aka our intriguing Magenta, then aniline yellow, then many other synthetic dyes followed suit, offering the fashion industry colours never dreamt of before. However, the brilliant lakes made from these were far too impermanent for artists. They would have to wait quite a bit longer. In fact, until the 1930s when Phthalo Blue and Green, both synthetic organic ‘lake’ pigments, were found to be also reliably lightfast. By then, dye manufacturers had become huge chemicals industries that had diversified into pharmaceuticals, would soon venture into plastics, and, for obvious reasons, had become pigment makers too.

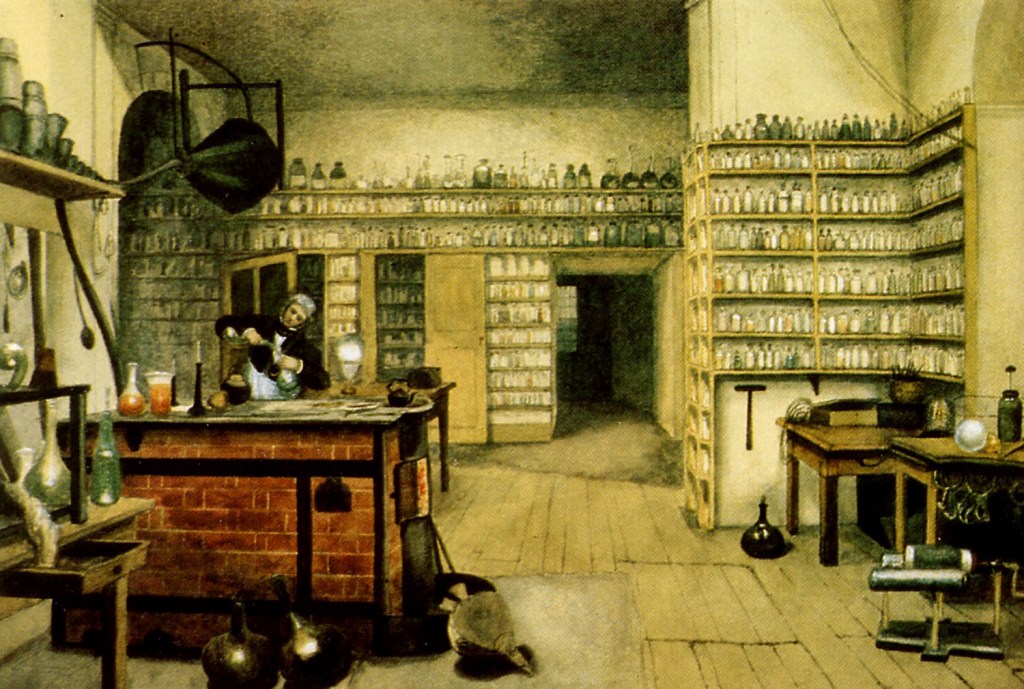

The rise of the Colourmen

If you look at the ingredients of an Alchemist’s cupboard in Medieval times (yes, you can find that on the internet!), it actually reads like a pigment manufacturer’s one: Alkaline salt, Alum, Antimony, Arsenic, Auripigmentum (that’s Orpiment), Bismuth ore, Chalk, Cinnabar, Saffron of Mars (that’s Hematite aka Red Ochre), etc. Yet what precipitated the demise of these more philosophically-minded gents in the 19th century was the growing understanding and nomenclature of The Elements. With this new Table, a more ‘respectable’, theory-based discipline emerged: chemistry. Yet, although these chemists understood the potential of newly discovered elements in the production of colour, these were often not exploited immediately and for other industries in which, let’s say, drying time or transparency was of little to no importance. As a result, some understood the necessity to bridge the gap between Science and Art, and another profession saw the light of day: colourmen. Often chemists themselves, not always colour-makers (i.e. those who made pigments vs colourmen, those who sell or make paint), these quickly become the artists’ go-to person. Today, even if some historical pigments are still made especially for them, the last colourmen usually only make paint.

I started this book with that assertion and would genuinely love to think of myself as a colourwoman (the title has a nice ring to it!) Still, their understanding goes way beyond today’s art store owners, who mainly open boxes of ready-made and sourced by someone else’s goodies. Sifting through Cornelissen’s archives of art materials, I chanced upon a correspondence between the firm and a paintbox maker, which involved serious discussions on the quality of the wood used for it, as well as for the included palette (had to be birch plywood with a mahogany veneer and stained edges) and the one used for the brush box (which had to be either oak or mahogany, with attention to the oak grain when possible, and with grooves precisely the size of an assortment of sable brushes provided) not to mention the screws which had to be of good quality but were not provided by the company which produced the leather handles. Another one, found at the bottom of a file containing a whole bunch of caviar producer catalogues (quite thought some Xmas order had made it weirdly into the things kept by Nicholas Walt, the owner), was, in fact, a very serious enquiry as to whether they could provide some inner membranes of sturgeons’ air bladders (to make Isinglass, an excellent fish glue, sometimes used as a varnish too!) These findings, and many others more directly relevant to pigments, made me realise how vital these highly inventive colourmen were in England’s 19th century. Winsor, Robertson, Reeves, Rowney, Middleton… so many of them made discoveries into Pigment’s possibilities and improvements to paint / art materials in general, some of their discoveries are still in use today. Their books and catalogues also better-informed artists… up to a point, as we shall see.

Later, I realised that colourmen had existed in England for much longer than that. Even if most are now entirely forgotten, their purpose seems to have changed very little from the first one we know of, artist and teacher Alexander Browne, who advertised himself via the 1675 edition of his book, Art Pictoria, thus:

“Because it is very difficult to procure the Colours for Limning rightly prepared, of the best and briskest Colours, I have made it part of my business any time these 16 Years, to collect as many of them as were exceedingly good, not onely here, but beyond the Seas. And for those Colours that I could not meet with all to my mind, I have taken the care and pains to make them my self. Out of which Collection I have prepared a sufficient Quantity, not onley for my own use, but being resolved not to be Niggardly of the same, am willing to supply any Ingenious Persons that have occasion for the same at a reasonable rate, and all other Materials useful for Limning, which are to be had at my Lodging in Long-acre, at the Sign of the Pestel and Mortar, an Apothecary’s Shop; and at Mr. Tooker’s Shop, at the Sign on the Globe, over against Ivie Bridge in the Strand.”2

Funny how I can imagine that Pestel & Mortar sign, swinging in the wind like so many of the pubs of old, all bright and coloured against the grey skies of London… a cheerful sight, promise not of a good beer but of a beautiful colour. And how I wish I could enter that little shoppe and rummage through all the treasures of this artist-turned-apothecarist. No more than I can resist entering any art store that comes my way today, can I resist pushing that shop’s door… in my imagination at least!

Others came up with ingenious new machines, such as Pierre-Louis Bouvier’s grinding mill and James Rawlinson’s improved one, which was immediately grabbed by Middleton, the most famous colourman of the era. The list of talented chemists who experimented with and discovered new chemical elements and compounds and personally got involved in commercialising pigments and dyes is too long to share here. But of course, too, industrial/chemical advances all over Europe and the US were instrumental in bringing on the colour stage by-products of their industries and research. We owe them not only the synthesis of Indigo and Alizarin but also the isolation of barium, cadmium, chromium, zinc, and titanium, which gave us entire families of pigments that you probably know well enough from your tubes for me not to have to spell them out.

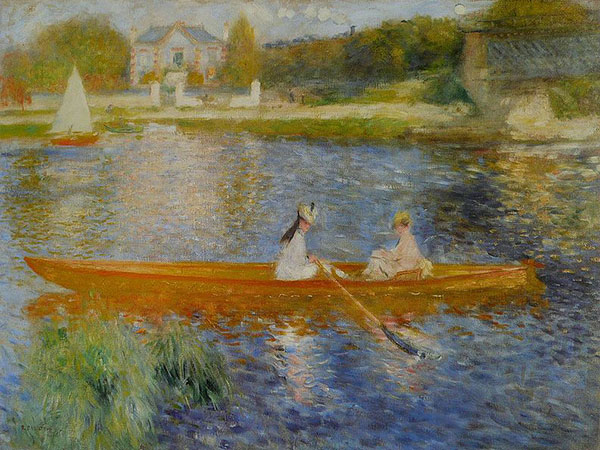

Although many elements were discovered around the late 18th century, it often took a long time, sometimes more than a century, for these to be used in the production and commercialisation of pigments and even longer for painters to give them a go. Amusingly, and although some avidly applied all the flashy new pigments straight out of the testing tube unto their canvases, most painters were quite reluctant, in fact, and probably correct in their caution as their original versions often came with issues. “I used chrome yellow which is a superb colour but which apparently plays nasty tricks.” lamented Renoir as his vibrant yellow darkened upon exposure to light. (These issues with the Chrome colours you will not encounter today, as their recipe has been rectified.) Also, despite the century seeing the rise of dedicated colourmen, the workshop tradition and production of paint was still initially strong, and it took perhaps a bit of time for artists to trust this new and improved version of vendecolori, again quite rightly so in some cases, as charlatans abounded too!

In my understanding, Winsor & Newton were the first to publish, in 1892, a complete list of their paints detailing their composition and permanence. Reading the Statement of Policy which accompanied the list, you get the feeling this was done under the pressure of their customers rather than their enthusiasm at transparency, and also to clear their reputation of deliberately keeping artists ignorant of their colours and potential shortcomings. Indeed, they quite squarely begin so:

“Manufacturing businesses exist, as a rule, not for the enforcement of moral laws on their customers, but for the satisfaction of the demands which those customers make; and while, for instance, we continue to be asked for Carmine and Geranium Lake, so long shall we continue to supply them. The artist is, in our opinion, the sole judge of his right to employ such pigments; and we, who use our best efforts to supply him with all he requires, have no intention of excluding them from our list of manufactures. We do not assert that such colours are durable; all we do assert is that they are as durable as they can be made.”3

It seems the ball was and (still is) in your ballpark. Do you hear that artists out there?

To be fair to colourmen, I can see two good reasons they were somewhat reluctant. In order to keep their commercial recipes proprietary, and that’s fair enough as the competition was quite acute at the time. (Still is, even if I can’t come up with more than a couple of handfuls of excellent paintmakers; in the end, one either buys their paint or… someone else’s.) Also, following in the footsteps of alchemists, most prone to cabalistic stealth, and painters’ workshops where materials, tricks and techniques were as secretly guarded as core values, I would venture it can’t have been easy to give up the mystique which detaining the so-called Secrets of The Old Masters would have conferred…

But the times were changing… fast! Boston, a thriving city at the heart of the American industrial revolution, is a good example of that. The Massachusetts Normal Art School, as it was then amusingly called (normal art?), was established in 1876 to support the Massachusetts Drawing Act of 1870, and it aimed to provide drawing teachers for the public schools and train professional artists, designers, and architects. You might exclaim: “Oh delight! A publicly funded university (which it still is, and now the only free art school standing in the United States) offering everyone drawing skills!” The truth had a more business-oriented flavour, however. Boston’s textile manufacturing, railroads and retailing boomed, but skills were lacking, especially in technology and draftsmanship. Civic and business leaders got together, founded the now world-renowned Massachusetts Institute of Technology, as well as the art school and, to be fair to them, the not-so-business-orientated excellent Boston Museum of Fine Arts too which meant art could now be enjoyed by all… a revolution in itself that one! (The Vatican had opened its doors to the public a century earlier, but the Louvre is only 77 years older than Boston’s museum, the Prado 51, London’s National Gallery 46, the Germanisches Nationalmuseum 18 while New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art was inaugurated the same year as Boston Museum of Fine Arts, in 1870.)

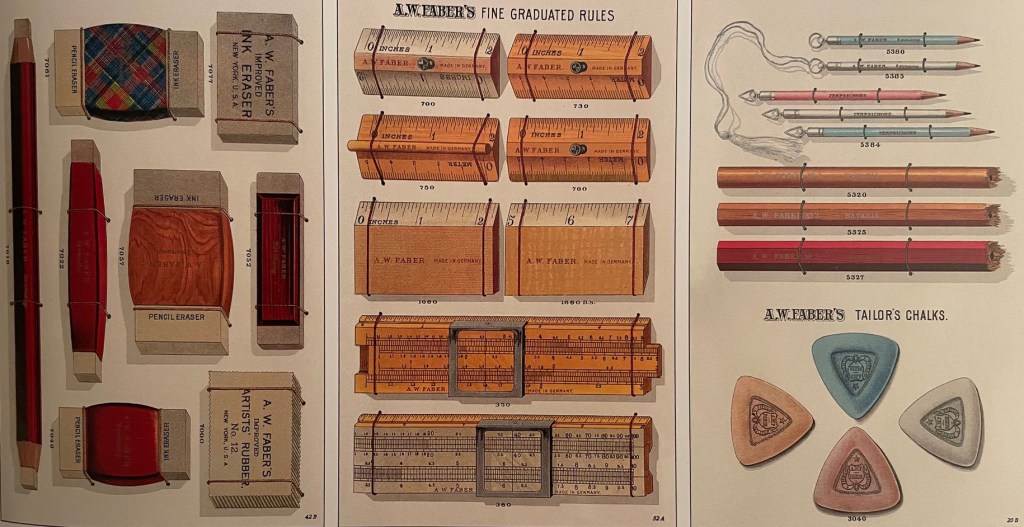

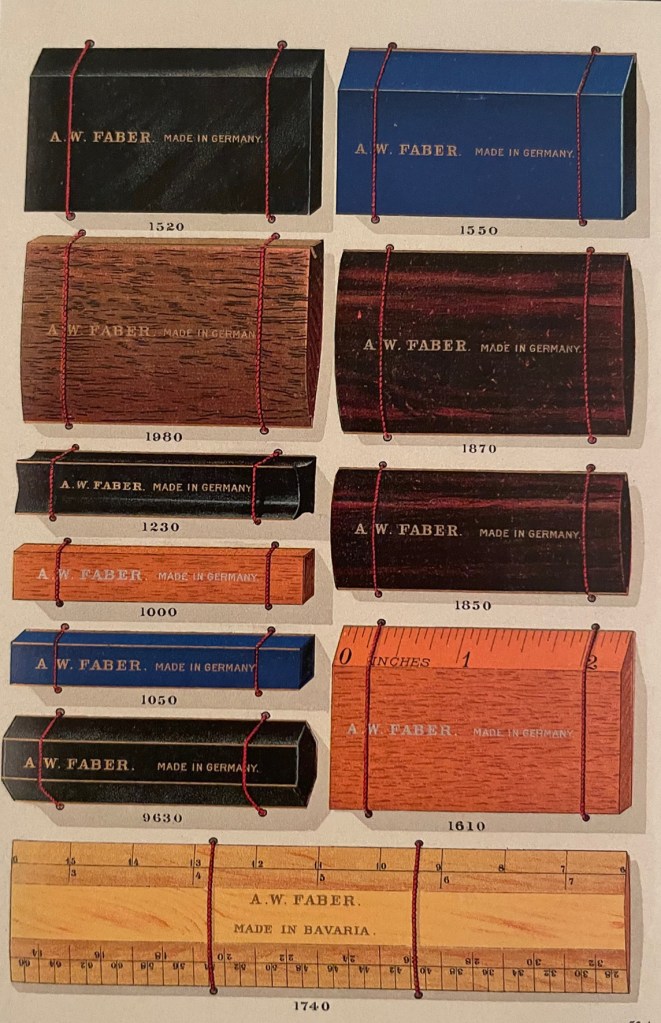

While some were trying to improve drawing skills, others were improving… the pencil! When one reads the chronicles of the Faber und Castell pencil-making family (they also made rulers, compasses and all sorts of technical drawing implements), one soon gets the feeling that it was not so much a business that grew during the Industrial Revolution as one enacting the revolution. Each of their inventions needed to design the next invention… It’s pretty thrilling to see the contribution of the modest pencil to this expansion/explosion of ideas and techniques. And to understand how, for better, for worst, each new branch of the company was a step towards building a multinational empire (sourcing here, planting trees there, manufacturing in factories all over the globe, etc.) Suddenly the modest pencil’s wood and rubber came from different countries in South America, the ‘lead’ from perhaps England or Hungary and the ferrule… who knows? But, again for better or for worse, this humble tool, in turn, allowing better tools and new techniques.

Would you be interested in having a look at

and read a little story about the twenty-five pigments in my fifth circle?

Click here

Jump to the next section of the book by clicking here

Alternatively click on the Table of Contents to browse the sections.

You can also subscribe to my blog at the bottom of this page,

and you’ll receive Hues in Tubes in your inbox… as it gets published!

Additional information & references

- quoted by Ball P. (2003) Bright Earth: Art and the Invention of Color, p. 274, University of Chicago Press, U.S.A. ↩︎

- Browne A. (1675) Ars Pictoria or an Academy treating of Drawing, Limning, Painting, Etching to which are added XXXI. Copper Plates expressing the Choicest, Nearest, and Most Exact Grounds and Rules of Symmetry Collected out of the most Eminent Italian, German and Netherland Authors ↩︎

- Winsor & Newton (1892), Statement of Policy. A commercial publication I found in the Cornelissen archive. ↩︎

Discover more from in bed with mona lisa

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

hi, I wanted to say how much I am enjoying these emails. I was employed at Vision Australia years ago when a French Impressionist exhibition was on at the NGV. We assisted in making the exhibition accessible for people with vision impairment. While organising audio tours a source we used (which I found fascinating) “Art and the Disordered Eye” (online) there has been scientific updates since it was written so there would be different articles. It explains why with age and eye conditions artists such as Monet and Van Gogh’s colours changed in tone. I thought if you have not seen it already that it may be of interest to you.

Warm regards,

Lynne Kells

Sent from Gmail Mobile

HI Lynne and thanks for such very interesting feedback… I had not heard of the film (and it seems it’s not available online anymore), but I took some time to answer as I wanted to know more and have found some great reviews of it… this subject and all the subsubjects of colour & vision are endlessly fascinating, aren’t they? I might be able to insert that info later in the book or I’ll revise the colour chapter because I find it too intersteting to not give it a mention so… thanks again! Sabine