WHEN?

Pigments in History

The sixth circle

Some pigments are coined Historical, some Modern, and some should be (in my humble opinion) called Contemporary or Post-Modern. Historical is a term that is definitely given to pigments known before 1704—when perhaps the first ‘modern’ synthetic mineral pigment, Prussian Blue, was created entirely in a lab (and entirely by accident too it must be said.) After that, the crossing line into Modern seems somewhat vague, to say the least. Some books and companies talk of Modern pigments thereafter, but most others seem to draw the line a bit later when the true chemical revolution happened and synthetic organic aniline dyes—and lake pigments made from those coal tar-based dyes—hit the textile and paint markets.

If inclined to agree, we could choose the turning point date of 1856, when William Perkin discovered his purple dye and promptly commercialised it under the ravishing name of Mauve, French for mallow, which sounded fashionable to Perkin’s ears. This first “unnatural” colour, as it was derogatorily coined, quickly spread an addiction, violettomania, which, according to the fashion critics of the times, could soon turn into a full-on disease: mauve measles! (Please note that this was not the first time purple rose to the level of a frenzy… In the first century AD, there was such a thirst for purple that the author and naval commander Pliny the Elder, whose recipe for making Tyrian purple survives, dubbed the craze for the colour purpurae insania, i.e. purple madness!)

I’m happy to pick either of these dates, both linked to important/exciting colour revolutions but what I find a bit odd is that there is yet another ‘modern’ boundary to be found—it seems mainly in the blurbs of paintmakers. There, Modern is used for pigments developed and used roughly since WWII.

I think we are missing a word! Just as Modern Art began more or less in the wake of these first industrial pigments, I suggest keeping the “Modern” term for these (as radically different from their predecessors as were the artworks of that time) while “Contemporary” or even better “Post-Modern” could be the one used for those pigments developed in the last 60 years… but will I convince you to start using that helpful distinction?

Today, thousands of pigments are duly analysed and categorised, and most of these, created in labs, end up colouring objects, from plastics to red apples, precisely.1 Post WWII, as markets and the demand for pigments lightfast enough to stand up to the most severe standards grew (imagine a paint for a plane which can be flying at -50c and, ten minutes later, land on a desert’s hot tarmac or one which will let the wood breathe, stand up to the vibrations of an electric guitar yet look impeccably glossy and cool!), tremendous efforts were poured—still are—and incredible results obtained in the development of permanent and brilliant colours. Quite a few of these have landed on our palettes too!

Still, pigments suitable for art paints are much fewer, of course. A standard range of acrylics or oils hardly supports more than 200, if that, as many mixes can be found there, and many indeed have been around for a century or more. So that I wouldn’t have bothered with a “Post-Modern” pigment section to simply emphasise the crazy colours we’ve come up with recently—Klein’s zingy ultra-saturated blue, phosphorescents, fluorescents, iridescents, pearlescents, pure structural, the blackest black and the pinkest pink, etc.—if, during those years too, a plethora of simply useful, stable everyday colours, ya’ know yellows, reds and blues, had not also come to be. Some have proven to be quite successful with artists, and some, being heavy-metal-free, might even slowly supplant older pigments, but the true reason they need a separate section is that contrary to previous ones which were usually mineral-based pigments, these are the babies of organic chemistry (as any hydro-carbon-containing materials of biological origin.) That revolution began circa 1858 when the structure of molecules and the links that form those molecular structures (a carbon atom must be linked to four neighbouring atoms) began to be understood. A few years later, the structure of benzene-based compounds, which we now call aromatics, was correctly mapped by Friedrich August Kekulé and unleashed the raft of synthetic dyes in all colours we just mentioned. At first, these struggled to produce interesting results on cotton (silk and wool, no problem), but slowly, towards the turn of the century, they conquered all supports… save the support of artists. The lake pigments produced from them were unstable and not lightfast until the first half of the 20th century when new organic pigments with these qualities emerged.

Reflecting their origins, these usually bear the most complicated of names. In the Azo family (it should correctly be called the Hydrazone family as these do not, in fact, contain an azo group) meet the Arylides and the Diarylides (OK, with a bit of imagination, these could sound like Greek goddesses) but how about the Napthols and the Benzimidazolones? While in the Polycyclic pigments, you might come across the Anthraquinones, Dioxazine, Isoindoline and Isoindolinone (will I ever tell those last two apart?), Perinones, Perylenes, Phthalocyanines, Pyrolles and Quinacridones! One has to laugh and… learn. What choice have we when all these names are on our tubes now? All are the result of high-tech chemical tweaking of crystal structures, and most of these, the so-called (by me) Post-Modern and (by paintmakers) Modern pigments, are, in fact, and as far as I’ve understood, dyes, laked pigments—sometimes also referred to as ‘toners.’ (You might have grasped this intuitively when you tried to wash out, let’s say, some Phthalo Blue, which is very high tinting, from your brush, skin or slab as this one is ever so hard to get rid of, having, seeped into the hairs of your brush, the pores of your skin or the crevices of your slab, in actual fact entered and dyed all these surfaces as no pigment ever would.) While not precipitated onto alum, as the historical ones were, the precipitation still happens, but onto a monohydrazone compound containing sulphur and/or carboy groups. Varying the coupling component in the reaction will give you what seems like an infinity of hues.

I’ll give you just one example, Benzimidazolone. Let’s admit it, I can hardly spell, let alone truly comprehend any of this. Benzi pigments, which cover the spectrum from greenish yellow to orange, are obtained through coupling to 5-acetoacetylaminobenzimidazolone, while those that produce medium reds to carmine, maroon or even brown shades are coupled to 5-(2-hydroxy-3-naphthoylamino)benzimidazolone… Wonderful! How exciting! Perhaps to some who understand, yes, and even to me when I try to wrap my head around how vast the comprehension of our complex world we have come to, while how mysterious it all remains, in a strange way. For example, hardly one question about gum Arabic has been solved. This ancient and modest amphiphilic binder (it likes both water and oil) is so complex we are nowhere near reproducing it synthetically, nor even close to totally understanding the structure of its molecule and how it interacts with other substances… So there is room for more research and exciting discoveries (possibly new colours too), and yet I hope you will agree that, despite being extracted from a compilation of essays from The Artist, published in 1810, the following quote is most appropriate not only still today but right now:

“Chemistry is to painting what anatomy is to drawing. The artist should be acquainted with them, but not bestow too much time on either.”

(Isn’t that a clever way to get out of a tight pigment spot?)

I feel this Post-Modern section cannot be ended without a word about Post-Industrial pigments if you will call them thus. There is a trend among many artists today to veer away from all ‘unnatural’ pigments, just as there is a weariness around solvents or even fossil-fuel-based binders paints, and, frankly, I get it. However, it’s hard to get high chroma paint out of pigments collected from the side of the road. And, if you only use these, you might also be missing substantial colour spaces or even the flexibility of an acrylic binder. But nothing and no one has been harmed in making your paint, and the loss of some ‘qualities’ might be the gain of a more sustainable art practice plus your peace of mind, so I can only applaud. Yet, although the practice might possibly be coined post-industrial, the pigments are quite the same as they ever were, beautiful Earth pigments or lakes from flowers and barks, and I don’t know that these deserve a new appellation.

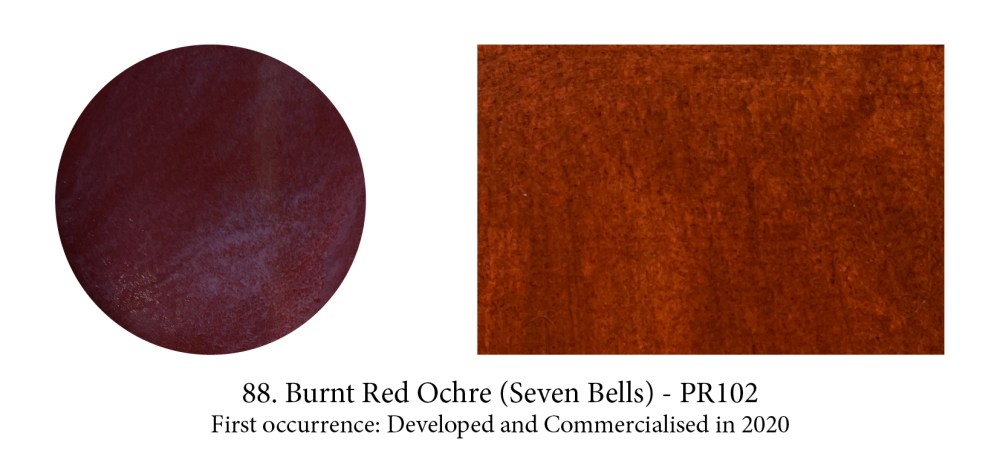

The last in my timeline does, yet it’s… the first one in it too! Red Ochre, a pigment we know for sure was in human hands around 70,000 years ago (probably long before), and 6 Bells Red Ochre, a pigment ‘born’ in 2020. Representing here both a circular continuity which enchants me—6 Bells is not a synthetic ochre— and a discontinuity—6 Bells is not quite as ‘natural’ an ochre as one you would gather from the ground. I enjoy the subtle dissonance… the same, but not quite. Do you remember me telling you that mines nearly always end up flooded? Well, England, which has been coal-mined for centuries, is more like Gruyere cheese than Cheddar, I can assure you. In some areas, nearly every village had a mine, or perhaps every mine ended up with a village, I’m unsure (probably both must have happened.) These are all long disused, closed, maybe even forgotten. Nevertheless, water gets in there, and after all the excavating and disruption inside the belly of Mother Earth, there’s much loose iron in there, too. When eventually the water overflows and the iron encounters oxygen… ochre is produced. And when that sludge hits the mainstream, as it will, and the stream enters the system, as it will, it clogs the pipes and creates all sorts of issues. Millions are spent in preventing this by the creation of decanting basins. Yet, after that process, something must happen to the sludge in question.

That’s when artist Onia McCausland comes in and suggests to the British Coal Board that, rather than disposing of it, somehow, this orange slime could be turned into beautiful, useful paint… but of course, my dear Watson! However, to do so and recycle these ochre residues into a luscious material artists will desire, many processes will be needed, including roasting it to the beautiful colour it is (not to mention Onia’s labour of love.) Yet this singular one, the result of an unlikely collaboration between Art and Industry, has not only become, in the hands of Michael Harding, a high-quality artist paint but also a luscious, non-toxic house paint.2 To be sustainable (economically), the operation will need to be scaled up, of course. Yet not excavating more ochres from the ground, plus saving tax-payers money from, literally, going down the drain, seems to make the whole endeavour not such an impossible dream, and I truly hope this complex/modest post-industrial pigment is opening a way for us to go in the future…

Would you be interested in having a look at

and read a little story about the thirteen pigments in my sixth circle?

Click here

Jump to the next section of the book by clicking here

Alternatively click on the Table of Contents to browse the sections.

You can also subscribe to my blog at the bottom of this page,

and you’ll receive Hues in Tubes in your inbox… as it gets published!

Additional information & references

- The market research company Ceresana analysed the entire pigment market for the fifth time in 2017 (the latest data I could find), and 10 million tonnes were sold worldwide that year. The production of paints and coatings accounted for 45% of total global demand (95% being Titanium White!) and only 1% was used in producing art materials. Processing of pigments in plastics ranked second at a considerable distance, followed by the application areas of construction material, printing inks, and paper. Source: https://www.european-coatings.com. ↩︎

- For more information on Onya McCausland’s 6 Bells project, go to: https://turninglandscape.com/ ↩︎

Discover more from in bed with mona lisa

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

One Comment Add yours