WHICH?

Pigment Characteristics

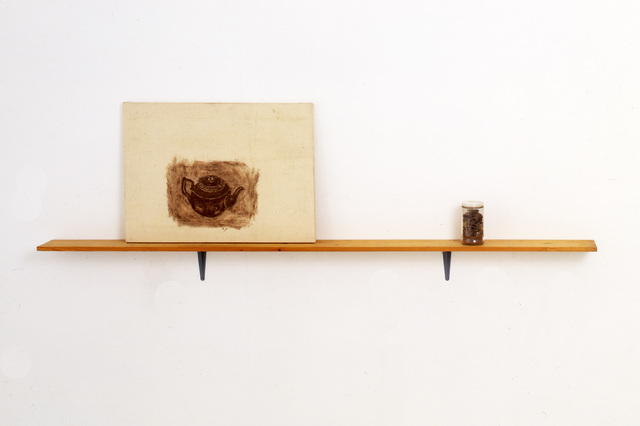

Firstly some pigments are pigments we can use, and some pigments are pigments we cannot use (to make paint.) This being said, I am not here to restrict your creativity or imagination. If, in the steps of artist Amikam Toren, you wanted to make a statement, pulverise your teapot to shards, mix the ‘pigment’ thus produced with a glue of sorts to paint… a teapot (or reduce your chair to sawdust and paint a chair with that) I have nothing against it. I was brought up with Magrittes on the walls and totally get (now that I’m grown-up) that a pipe you cannot smoke is not much of a pipe, nor is Neither a teapot nor a Painting much of a teapot anymore—to a tea drinker at least. And as for the “nor a Painting” bit, I will leave that to your judgment and clever mind to figure out… too dangerous to venture on that one. (Had no idea I could tread a fine artistic line and perhaps find myself in a politically incorrect situation around a simple statement about pigments, but these days you have to be ever so careful… as you will see.)

I’m liking these works and happy the artist is forcing us to notice and look at this amazing material component of paint, pigment. But still, I must defend my point of view. When I say, “some pigments are pigments we can use, and some pigments are pigments we cannot use”, I mean we shouldn’t use them if we want to make ‘proper’ paint… (full definition of proper pigment for paint coming soon.) Past those pigments which will never be turned into anything material, even so many of those that we somehow manage to extract from their original surface do not meet the basic requirements. For example, if in spinach you might find two kinds of chlorophyll pigments that give it a deep green colour and two accessory pigments, beta-carotene and lutein, both yellowish-red pigments, try as you might, you will never extract these biological pigments and make a useful paint out of them. Shame when you think how much artists have wanted to paint verdant landscapes and how few green options there were for all those centuries past but above pigments, like most, are not suitable for an artist’s purpose, even if they’re impossible to get out of your kid’s bib. (The price you pay for even trying to feed him spinach, of course.)

Pigmentum, with which you can pingere, is the king of that castle and proudly looks down from its tower onto dyes and lakes (pigments made from dyes), as these are primarily fugitive—while I’ve noticed with amusement another ring of contempt/condescension even dyers frown upon: stains! (Think weird things like coffee, blood or… spinach in art materials’ world.) Pigments, dyes and stains nevertheless share that they are all made from an incredible array of primary materials and processes, but rules to be admitted to the elite Material Pigment Club are, in fact, quite strict. You must be a solid particulate (practically) insoluble in, and essentially physically and chemically unaffected by, the vehicle in which you might be incorporated (essentially oils, resins or water.) Today’s internationally accepted definition is hardly more romantic than my ‘surface’ approach. It seems to define one somewhat by what one cannot do rather than clearly explain what one does or is. But I suppose it’s, at least, a rope to hold in this otherwise choppy sea of words.

To use pigments, even turned into a paint paste, doesn’t imply you are making art, of course. For millennia, I presume that, if indeed we were using paint, our field of expertise was more in the body painting department than any representational cave art… and today’s cosmetic industry, which raves and boasts about highly pigmented lipsticks, foundations and whatnot, seems to have taken the relay!

But, at any rate, should one hope to be admitted to the even more posh and exclusive circle of the Art Pigment Club, then the entry conditions are radically more stringent, as the other considerations just mentioned become essential too: colouring power, lightfastness, mixing permanence, siccativity, fineness, compatibility with different pigments and binders, etc.

So, if not as hard as splitting atoms, and on the whole not as dangerous either (if somewhat toxic at times), you must understand that it took forceful, sometimes even disruptive methods to ‘extract’ colour from the raw ingredients of our planet and turn these into usable art pigments. It’s not all bad either, as ingenuity and sophistication were needed—whether the colour was born in a crucible or a landscape. Nevertheless, Il faut souffrir pour être belle is (of course!) a French saying that could be translated: “To be beautiful, one must suffer” and applies perfectly to our relentless colour/pigment pursuit. Processed by extracting, washing, precipitating, heating, burning, calcining, fermenting, adulterating, acidifying, subliming, hydrating, filtering, levigating, grinding, digesting, sophisticating, sieving, decocting, distilling, decanting, precipitating, filtering, hammering, pounding, straining, smelting, scaring, evaporating, crushing, roasting, etc. pigments somehow, and under no little duress, came and come into existence. Beautiful they were, they are, but suffering to get there? Sure too. As for willingness… (But then again, who knows, there might be some awful exhibitionists in Pigment World who think all of the above is perfectly justified to display their tantalising colour and have the privilege of ending up as Botticelli’s Venus!)

Jump to the next section of the book by clicking here

Alternatively click on the Table of Contents to browse the sections.

You can also subscribe to my blog at the bottom of this page,

and you’ll receive Hues in Tubes in your inbox… as it gets published!

Additional information & references

- Talking of Ceci n’est pas une pipe… the above clay pipe fragments are a pigment… to some anyway! And certainly, in the hands of my friend Lucy Mayes, the creative force behind London Pigment, a company dedicated to making pigments “from London”: wildflowers growing on sidewalks, mudlarked clay pipes or Thames spuds (so-called as the tides of the river have worn these old bricks thrown in the river… round), Victorian copper pipes (can’t smoke these), burnt

mopeds and the ilk. Lucy’s work proves that you can probably make a pigment/lake from almost everything. Yet are they lightfast? Probably only some. Useable? Beautiful? Most certainly… ↩︎

Discover more from in bed with mona lisa

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

One Comment Add yours