WHICH?

Pigment Characteristics

This being said… there’s indigo! As you might know, indigo is a plant, but there are more than 750 species of indigofera shrubs, herbs, and even trees, so it might be just a little challenging to identify, although, of course, if you crush a few leaves in your hands, these will turn… blue! Local varieties were used all over the planet to produce the colour (alongside its most ardent competitor, isatis tinctoria, aka woad), yet for centuries, the one that interested us the most was indigofera tinctoria, dubbed ‘true indigo’. Perhaps because it was the most colourfast dye, it became the most popular one, used the world over. Possibly, too, there was that little bit of magic about it that made it so attractive.

Despite its undeniable colouring properties in the vat and most of us knowing indigo as a dye, it is, in fact, a pigment. Oh, a lake pigment, then? No, a real pigment. You can grind indigo cakes into particles fine enough to be milled in oil or dispersed in water and turn these into paint without the need for further processing. The paint produced thus is a rather poor one, which was often used as an alternative to more expensive blues. (Don’t worry, the one in your “Indigo” tube today is not indigo!) In the 15th century, Cennino Cennini already suggested using indigo only to “ imitate […] azzurro della magna” (azurite) or to “ counterfeit ultramarine […] when painting in fresco.”

Still confused, I was. But that’s because indigo is a rare one, a babe that, indeed, cannot be dissolved into oils, resins or water, so it’s correctly labelled a pigment. Yet, when some magical ingredients are added to a vat of indigo (there are quite a few recipes), it does not entirely dissolve but releases an amber or yellowish-green colour, which will impregnate your wares. Sometime later (again, depending on the methods), when what was soaking in the pot hits the air, an oxidation process happens, and mere seconds will turn it under your eyes into one of the most divine blue possible… further dips, will ensure endless variations of the blues.

So, do we need to reassess the official definition of pigment when some can be used to dye fabric? Possibly, yes. Possibly, too, it follows the rule of Pigment, that there are no rules… generalities, yes, but exceptions, always.

P.S. To be fair to indigo, it must be added that it can make wonderful paint if you improve the recipe. It also requires a somewhat rare ingredient, but once you find it, indigo can be turned into one of the most durable and lightfast pigment existing. For centuries that technique was lost (or was it?), but the stunning blue in question had survived in the humid and hot Chiapas jungle unaltered, waiting for further scrutiny. Blue fragments were first found, and it had seemed a totally new colour promptly baptised Maya(n) Blue, but… what was it? That question remained unanswered for quite a while.

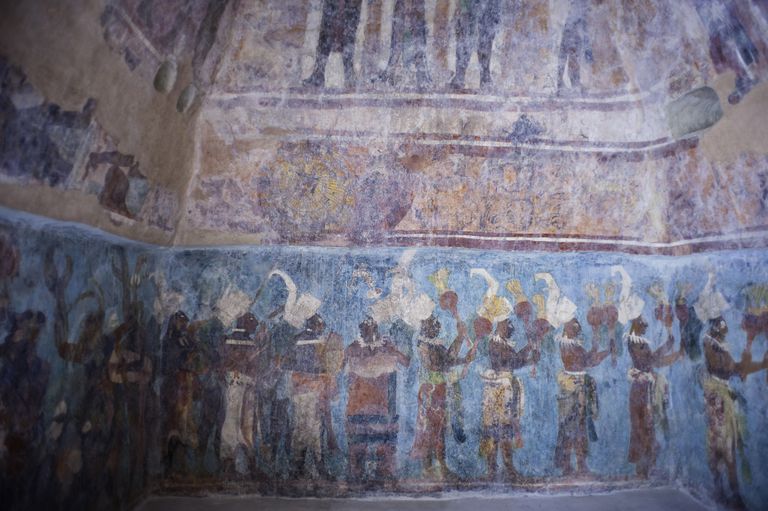

The first analyses deemed it clay, a blue clay, perhaps? Maybe not, and yet it wasn’t until 1946 when an entire fresco of a procession of dignitaries around King Chan Muán was discovered inside a Mayan temple, that its blue background stirred enough interest for further research. Again clay was found, attapulgite, a very white type of palygorskite clay. As for the blue… it kept its secret. (Indigo, being a pigment, is virtually insoluble in almost all liquids and solvents, remember, so pretty hard to analyse.) In fact, it took almost another sixty years and more sophisticated investigation equipment to understand the unique chemical bond of indigo-dyed-clays fully and… the right temperature for our recipe! A temperature of above 150c is needed. Under that heat, indigo only attaches itself to the clay’s surface. On its way to 300c, however, the indigo molecules dissociate and can then enter the nanotubes of this particular clay and bond with them. This is also possible because the water in the fibrous channel-containing structure has evaporated, and indigo can take its place. Only then is the reaction irreversible, and indigo, protected in these little casings, can now survive centuries of rain and shine happily. Nano-technology in action, so many centuries ago, how about that?

Scanned electron microscopy (SEM) of three types of clays taken from different websites.

It’s easy, really. Once you know how. And yet some dark magic (perhaps not compulsory if you want to try the above recipe) might still have been needed, as it seems copal incense played a part in the mix while the pigment was made during sacrificial rituals in which men were then covered with this blue and thrown into a sacred well to appeases the provider of corn, aka the rain god Chaak. When that Cenote Sagrado well was dredged some years ago, along with bells, rings, masks and many human bones, a five-metre layer of blue pigment was found at the bottom of it… told you pigment was insoluble, didn’t I?

P.P.S. The Mayas perhaps didn’t invent Maya blue, as it has also been found on artefacts of earlier neighbouring civilisations, such as the Zapotec. Also, it was still around when the Spaniards arrived, and literally kilometres of their churches’ heavens were eventually painted with it. However, and this is most baffling again, despite, for example, cochineal being so massively exported to Spain and the fact that they produced tonnes of indigo for their use in conquered Guatemala, the conquistadors never put two and two together apparently and thought to export the celestial Maya Blue to Europe.1

Baltasar de Echave Ibia, The Immaculate Conception, c.1620. Museo Nacional de Arte de Mexico, Mexico

Jump to the next section of the book by clicking here

Alternatively click on the Table of Contents to browse the sections.

You can also subscribe to my blog at the bottom of this page,

and you’ll receive Hues in Tubes in your inbox… as it gets published!

Additional information and references

- If you have an interest not only in Maya(n) Blue but the other Mayan colours we can now see on some paint stands, you might enjoy my M.A. research about them. How are green, red and yellow produced? Do they also use palygorskite clay? And then, which colourant? Indigo’s role is exceptional in the production of Mayan blue… [Online]. [Accessed 29th January 2025]. Available at: https://cp652001082.wordpress.com/ ↩︎

Discover more from in bed with mona lisa

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

One Comment Add yours