WHICH?

Pigment Characteristics

In the elitist Art Pigment Club, all members, whether pigments or lake pigments, belong to two categories. The idea being, probably, that you don’t mix with the wrong crowd, as these refer specifically to the pigment’s origin, regardless of its structure or chemistry.

You are either Organic or Inorganic and either Synthetic or Natural. The fun bit is that they combine! So that you can be Organic/Inorganic and Synthetic or Organic/Inorganic and Natural. On the whole, these nerdy classifications add more confusion than they are helpful, I find1, but still I need to tackle these definitions as you will see them on members’ lapels in the Club every time you meet (i.e. on every reputable paint and pigment label.)

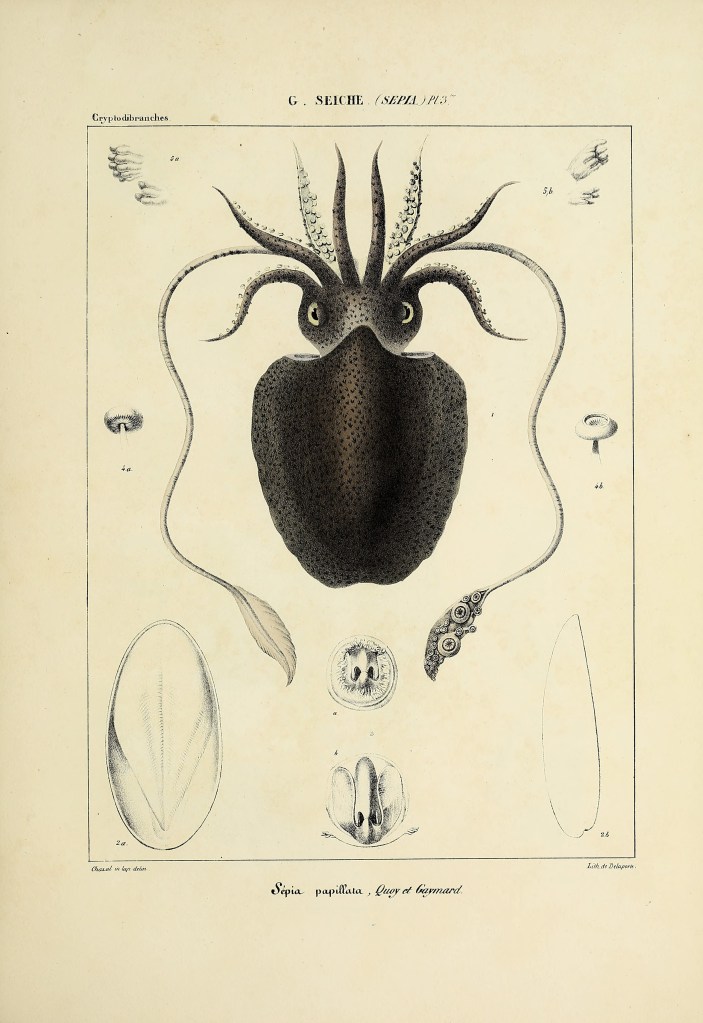

When Linnaeus devised his landmark classification system, he divided nature into three kingdoms: two living (plants and animals) and one nonliving (minerals). Organic pigments belong to the first two kingdoms and are made with something that was once alive and… if you think we haven’t tried it all, think again! Men have crushed mummified bodies (good in oils for shading apparently but not great in watercolours); macerated, then mixed with urine, wood, ash and water to extract a few precious drops of dibromo indigo from the hypobranchial gland of 250 000 carnivorous murex branders or murex trunculus (these are small marine snails) to create one ounce of purple dye; picked tonnes of tiny parasite bugs on cacti then shipped them to the other side of the world to be turned into a dye as well, then a lake paint; extracted pearl essence from the scales of fish (mostly herring and sardines); forced-fed poor Indian cows (and strangely in that case not sacred) nothing but mango leaves to collect their orange urine and turn that into a pigment too; charred ivory and other bones; extracted litres of sepia ink from the cuttlefish’s ink sacs, black ink from the octopus’ and blue ink from the squid’s… If this reads like a list of horror stories, please rest assured that not all organic provenance was that bad by any means. Many fruits, berries, nuts and other bits of plants (roots, bark, leaves and stems, seeds and blossoms) have/are also used to produce colour more gently.

So far, I hope that’s pretty straightforward, but now I must introduce you to the most challenging organic pigments to wrap your head around. These are synthetically produced from petroleum, tar or coal. In short, everything we group nowadays under the name of fossil fuels—which helps remind us of their origin, I suppose. Think more decomposed vegetable matter and microscopic organisms such as plankton rather than mammoths or dinosaurs but still, whatever they were millions of years ago, these were quite alive. As a result, most modern pigments produced in labs being fossil fuel-based are… organic! And, just as the Historical ones mentioned earlier, many are akin to dyes and often combined with inorganic substances to create pigments.

A true revival of ‘gentle’ organic pigment-making is happening right now in people’s kitchens and sheds. In art stores, however, if you dismiss these fossil fuel pigments, there are virtually no organic pigments left at all… and not only because we’ve run out of murex2 and mummies (as we have!) but, again, because these were mainly fugitive colours which more lightfast ones have replaced.

Inorganic pigments go under the names of Mineral or Earth pigments and range from precious metals like gold to semi-precious stones like malachite or lapis lazuli to abundant, inexpensive Earth pigments: iron oxides, ochres, clays and chalks, offering a palette ranging from browns to reds to yellows to white, and, less frequently, some natural violets or greens.

Many inorganic pigments were synthesised at some stage. These, although structurally and chemically similar to the natural ones, came to be known under another name as we saw3 but, sometimes… not! Minium’s name, for example, stuck to its synthesised alter-ego, Red Lead, and to those miniaturists using it so lavishly in their works (nothing to do with the ‘mini’ size of their paintings!) On the other hand, Vermillion was often used to name its mineral counterpart Cinnabar and Red Lead sometimes too, so… they were confused back then and no wonder we are too today when we try to navigate old references and texts. More recently, the industrial revolution brought on the palette an impressive range of artificial inorganic pigments, such as the Cadmiums, Cobalts, Mars, etc. which also could be mined but are much more cheaply produced synthetically. These sometimes offer advantages, too, such as finer particles. Whether natural or synthetic, they usually have just one name, and we shall dive into them in the next section.

There are (of course!) quite a few pigments that are both. Historical lakes, which are, by composition, organic and inorganic, being a combo of an animal/vegetal extract and an inert material, are sometimes called hybrid pigments but classified as organic as the main ingredient in any given pigment—its colour component—will win the classification.

This is the rule but (of course!) one that can’t apply to DPP hybrid pigments. Have you, by any chance, noticed this reference on some of your tubes? At first, I thought the abbreviation was for “deep” until I noticed the two Ps! What these letters stand for are DiketoPyrroloPyrrole pigments (you now probably agree it’s a good idea they didn’t write them in full on your tube and other companies sell them under the abbreviated name of Pyrrole Orange/Red/Scarlet.) These relatively recent hybrid pigments are blends of an organic and inorganic pigment (don’t ask, please don’t). The idea behind producing them was to get the best of both worlds: organics’ high chroma and tinting strength, inorganics’ lightfastness and opacity… but that’s as much as I know about them; I don’t know why they are labelled as organic only, and I don’t even know if they are worth the price you pay for them (nice non-toxic colours, though) but they are now available in some ranges.

Finally, and yet again, there could be more of them out there I haven’t come across or realised were naturally hybrid pigments, but I’ll tell you the tales of a couple of Historical ones, just… because.

Blue Babe, one of the main attractions of The University of Alaska Museum of the North, Fairbanks, AK, U.S.A.

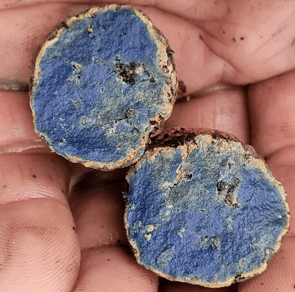

The first is Vivianite, a most curious one belonging to the group of magnetic pigments that, under your brush, will interestingly shift from grey to blue to green. It often goes by the name of Blue Ochre, and although it is an Earth pigment, this is a misnomer as it is not an ochre. It’s an aqueous iron phosphate that looks almost like transparent glass… until it takes on its blue colour. I had encountered a few nodules of it unearthed by some Insta enthusiasts, but, one day, I came across Blue Babe. The babe in question was found in Alaska in 1979, a nearly complete mummy of a bison covered with a blue chalky substance. That mineral coating is Vivianite, produced when phosphorus from the animal tissue reacted with iron and water in the soil, gaining the pigment an entirely new category, that of a “biotic” mineral—at least that’s how Melonie Ancheta, a Vivianite specialist, described it to me!4 Because, if the end product is indeed a mineral, it has needed life forces, has had a life span and somehow expired into another chemical state with… a different colour—as the pigment, when exposed to air, turns to blue. (Any chance that reminds you of Indigo?)

You rarely find a Vivianite bison, though. Usually, this is what the nodules look like. Photo provided kindly by Scott Sutton (aka #Pigmenthunter), talented artist and enthusiastic pigment collector.

The second one is found in specific places in the world and has been used by the Mesopotamians, the Indians, the Japanese, the Egyptians, the Greeks, the Romans and the Aztecs to caulk boats, waterproof baths and tunnels, consolidate fortifications, cast statuettes, set jewellery, create pavements and as paint too of course, or I wouldn’t mention it. In 312B.C.E., the Seleucids and Nabateans fought hard for the place where it occurred naturally. The first oil war not quite, although… Have you guessed what it is? I’ll give you a hint. It was used to soak the shrouds wrapped around bodies and eventually gave its Persian name, mum or mumiya, to the embalmed corpses themselves. This elusive dark brown glazing friend, annoyingly sticky and beautifully transparent, is known as Bitumen (or Asphalt.) Tar sands are natural occurrences of bitumen, and that name precisely sums up its two components: organic crude oil, tar, and non-organic sand. (And if that doesn’t sound too sexy, look at what Bitumen can become in the hands of an artist!)

Jump to the next section of the book by clicking here

Alternatively click on the Table of Contents to browse the sections.

You can also subscribe to my blog at the bottom of this page,

and you’ll receive Hues in Tubes in your inbox… as it gets published!

Additional information & references

- You’ll soon understand why in the I had picked black, part II, post. ↩︎

- Extinct would be something of an exaggeration, but still, they have become rare in the Mediterranean and the dyeing trade even more. In Mexico, the Mixtec community still dyes in purple, however, but with another variety of molluscs, the purpura patula. They don’t kill them in the process but delicately put them back into the little nooks of the cliffs, with a dangerous drop into the ocean, where they reside. Milking the marine snails is a laborious process. After finding a shell, gatherers release the urine, then the precious few drops of pintura directly onto wool or cotton thread. The white secretion soon turns the yarns yellow with air, then green, and the sun will give it its finishing touch of purple… yet another bit of oxidisation magic! (Picture by Eric Mindling and Ana Paula Fuentes, Traditions Mexico) ↩︎

- Malachite/Green Verditer, Azurite/Blue Verditer, Minium/Red Lead, Cinnabar/Vermillion, Orpiment/King’s Yellow, etc. ↩︎

- If Vivianite has titillated your curiosity, I suggest you read the excellent article by Melonie Ancheta: Revealing Blue on the Northern Northwest Coast (2017) in the American Indian Culture and Research Journal 43(1) [Online]. [Accessed 29 January 2025]. Available at: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8s75k7jn ↩︎

Discover more from in bed with mona lisa

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

One Comment Add yours