WHICH?

Pigment Characteristics

I need to address permanence here, a term not entirely synonymous with lightfastness in the paint world, although UV deterioration is an aspect of it. But, permanence needs a minute’s attention because if some pigments are friendly to other pigments, some are dangerous company…

To and by itself, a permanent paint should experience no significant shift of colour, and that’s the least you can count on. That your green remains… green. Verdigris, the pure product of a copper corrosion process, does not. Not only does its colour change in the first months (normally from a teal colour to a green hue), but it keeps doing its ‘thing’, dramatically darkening in the process. There were ways around that, of course, or it would not have become such a common pigment, but if you still see “Permanent Green” on your tubes, it’s because for many centuries, green was all but. It also didn’t enjoy the company of sulphur (which, in truth, none do as sulphur pigments are quite acrid.)

Today, of course, one takes permanence for granted, and, for sure, this is not something you should worry about too much as pigments pretty much all behave in society now. (Which is why permanence is hardly ever rated on tubes anymore.) But that certainly was not the case in the past. 1Naples Yellow genuine would change colour when in contact with iron. Orpiment and Realgar were incompatible with other commonly used lead and copper-based pigments such as Flake White, Verdigris or Malachite. Cadmium Orange and Red, quite happy to mix with Lead White in oil paint, used to react nevertheless to the lead the first tubes were made in—until tin was found a better option. The tubes’ surface darkened from the inside formation of lead sulphide. Cadmium Yellow, which, on the other hand, actually prevents Lead White from darkening in paintings, used to be very reactive in the presence of most heavy metal paints such as Emerald Green and darkened mixtures of Naples Yellow genuine or Chrome Yellow and on…

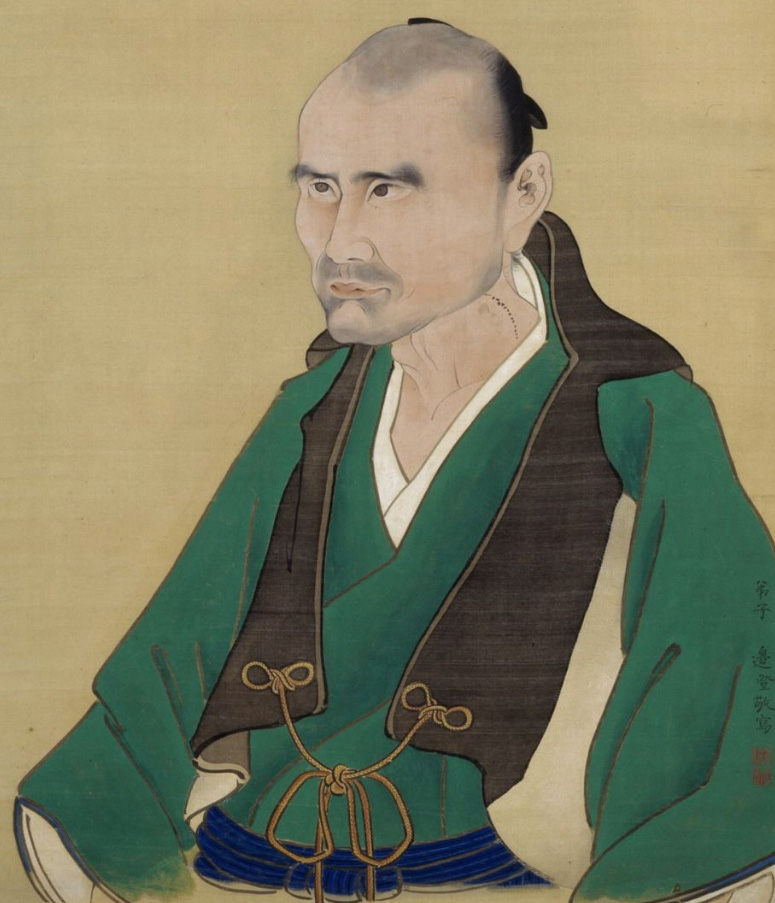

But if you exclude the tricky Verdigris and the reaction of pigments when in presence of other pigments, there are still some, such as Smalt (often used in stead of the more expensive Lapis), that simply shift over time. It’s not that they are not lightfast, they don’t fade, but they change colour! When Velázquez painted his Immaculate Conception (above), the blue must have been Immaculate indeed and he wouldn’t have known that, eventually, the chemical components of Smalt have a tendency to migrate… It’s a bit odd to even imagine that, quite frankly, but it happens and so, nowadays when Light hits Smalt its altered chemical composition give us, instead of a luminous blue, something of a dark bluish grey. (That’s why so many of the skies in paintings do look much sadder than when these were painted.)

In short, artists nowadays have it pretty easy because imagine that, on top of the quest for that elusive hue you have in mind, you had to take into consideration every time what not to mix with what, what might turn pale or dark with this or react to that. Or that you needed to add an isolating coat between layers of paint just because you’ve used Verdigris or another copper-based green. It might not sound like much, said like that, but what the above really means is that generations of painters, having no alternative pigments, could not add white to their yellow and orange, nor to any kind of green virtually… How would you feel if you were told not to do so today? Would you still envy the limited and ever-so-tricky palette of the Old Masters?

P.S.: Smalt is still around in your tubes today but… it’s a hue, a ‘permanent’ fake you need not worry about.

Jump to the next section of the book by clicking here

Alternatively click on the Table of Contents to browse the sections.

You can also subscribe to my blog at the bottom of this page,

and you’ll receive Hues in Tubes in your inbox… as it gets published!

- Remember, too, that pigments were hand-coated in their binder back then, and so not as well as is the case now with triple roll machines, and that this could explain in good part that. ↩︎

Discover more from in bed with mona lisa

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

One Comment Add yours