WHICH?

Pigment Characteristics

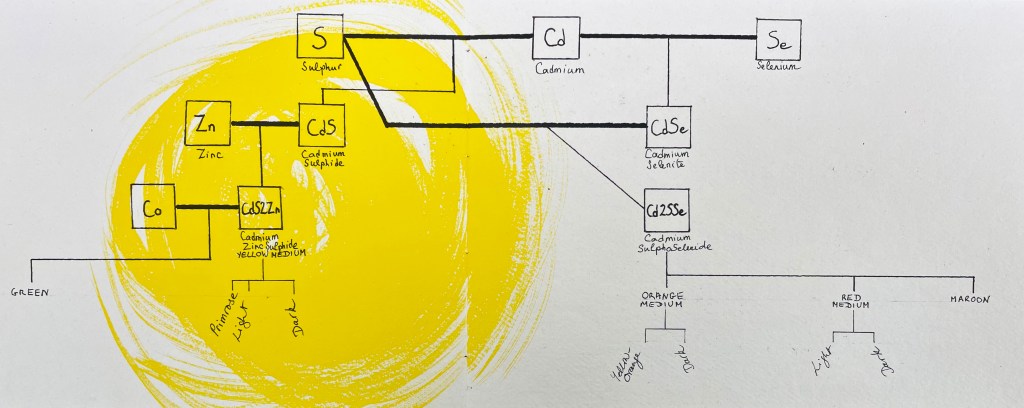

As promised, now is the time to dive into the pigments we play with on our palettes that get their hues from their chemical composition. The Cadmium family is a most interesting, if confounding, example of this. Establishing the family tree of the primo-genitor, Cadmium Yellow, was quite epic, I can tell you, and it revealed to me how much more complex things are, in actual fact, than what I had understood previously. Sulphur seems to have married both Cadmium and his daughter-in-law Cadmium Selenite. From his first marriage was born Cadmium Sulphide, who married Zinc, and their union gave us Yellow Medium and, eventually, Yellow Primrose, Light and Dark too. (The union of Cadmium Zinc Sulphide to Cobalt Blue also gave us Cadmium Green, but that’s just a yellow/blue mix, so it doesn’t count, really). On the other hand, Cadmium Selenite (the daughter of Cadmium’s union to Selenium), after meeting Sulphur, produced a charming little compound, Cadmium SulphoSelenite, who defiantly needed no partner whatsoever to produce Orange, Red and Maroon in all their variable hues (all that is required is to replace the sulphur in the lattice with increasing amounts of selenium, a totally transparent stuff which broadens the spectrum which the pigment can absorb.) Gosh!

Today, it is usually the crystalline structures of pigments that send variations of reflected or transmitted light, and offer us variations of hues with the same chemical component. As we understood how to alter the crystal lattice of structures, we produced distinct pigments under one family/umbrella name (same-same chemical constitution). These became known as polymorphic pigments. Good examples, you might know, are Phthalo Blue, a nearly perfect ‘in the middle’ blue, often found in red and green shades corresponding to two structural formations or the tantalising Quinacridones—these golds, oranges, reds, pinks and purples also the result of slight variations in the lattice of their crystal.

I can nearly hear you say: that’s a lot of chemistry!1 And yes, it is. But the word “structure” should have rung a bell and alerted you that it’s also a lot of… physics! And BTW, don’t imagine I really understand any of this for one minute, so neither do you need to, probably. But I love this stuff… Still, I’d better emphasise once and for all that Paint—all of its components: pigments, binders, additives, fillers, extenders, etc.—is, however charming an end product, actually the result of many centuries of passionate research, persistence and ingeniosity from generations of art-chemists and other lab rats. If this is not your cup of tea, maybe humbly thank Hermes Trismegistus, the central figure in the mythology of Greek alchemy and alleged author of Hermetica (my point precisely), that some have come into this world willing to understand these things, for those dedicated ones have created and refined the wonderful colours. While all you need to do really is keep on breathing and… painting.

This said, what might be helpful to grasp is that most modern pigments, the structures of which could be tweaked come, as a result, in families. So the above list goes on… Meet the Azos a very large family indeed (80% of all organic pigments) mainly in the yellow to red range: the Hansas, Arylides and Diarylides are all in the yellows; the Perylenes in crimson, red, maroon, green, and even black and the Pyrroles which offer the toxic-wary bold alternatives to the Cadmiums in the orange/red colour spaces. Anthraquinones are a large family of pigments, too, but they are usually only available in deep blue or red in art stores.

As for all the other pigments? Well, these, usually Historical ones, are lone wolves, quite happy and proud of their uniqueness, I suppose. But, where once pigments were all such individuals roaming the planet, not unlike wolves come to think of it, there are hardly any left these days… endangered species, really.

Jump to the next section of the book by clicking here

Alternatively click on the Table of Contents to browse the sections.

You can also subscribe to my blog at the bottom of this page,

and you’ll receive Hues in Tubes in your inbox… as it gets published!

- An amusing example of this is the French paint company Pébéo. Initally they produced lead-based house paints and their name was Pb0, i.e. lead oxide, the element! ↩︎

Discover more from in bed with mona lisa

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Dear Sabine,Thank you for including a pic of Cornelissen pigments.Lucy has a pigment book out

It is my absolute pleasure to be able to use some of the pictures from your wonderful collection (as it was to clean and catalogue that treasure trove!) and, yes, I know about Lucy’s book. I have preordered it and am now patiently waiting for it…