WHICH?

Pigment Characteristics

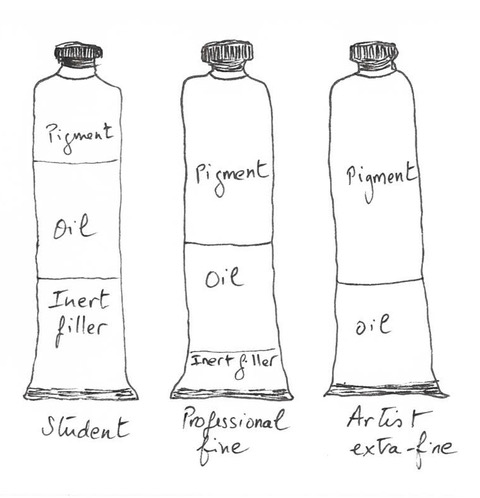

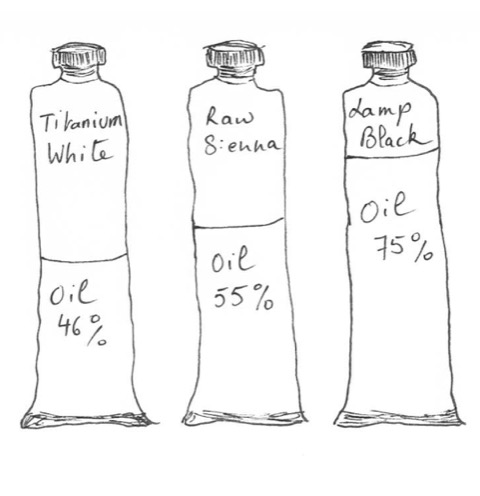

Some pigments are thirsty, they are not going to turn into paint before they’ve had their fill of oil… and some. Lamp Black might be the worst offender if offence there is. This is why comparing quality between brands, as is often suggested you do by comparing pigment concentration like so,

could give a confusing impression or is, at the very least, an incomplete picture. Of course, the more you add filler, the more you add nothing, as we’ve just said, but let’s now take paint with no filler whatsoever as a premise. It is still quite possible that the Artist tube above correctly represents the amount of pigment in a tube of Titanium White or Prussian Blue. Nevertheless see what happens with Raw Sienna (could be others, like Alizarin Crimson) and how little pigment content is left in the last tube; could be Raw Umber or, with even less pigment, Lamp Black. Because, well, because… some like it oily! (Which is why, further down the track and in the places where you have used a lot of Raw Umber or Lamp Black, you might find some ‘sinking in’, a dullness of the area. This is the way those pigments are letting you know they are, in fact, still thirsty, begging you visually to give them more and “oil them out.” Do that, Raw Umber lovers, but in between layers, not on the last layer of your painting!)

Every reputable brand claiming their paints are “highly pigmented”—as they do, and I’m not disputing that—is talking of adding only the minimum oil needed to coat every single pigment perfectly and filling every little space between those particles. That Critical Pigment Volume Concentration, CPVC, could be much oil and not much pigment because that’s what’s needed. A friend of mine interfered with my technical explanation to her husband one day (I was obviously not quite reaching him) by making an analogy to pesto. Some nuts she uses, such as macadamia, need a huge amount of olive oil to turn into paste, and some, such as the classic piñon, very little. But in the end, apart from taste, had he noticed a difference in the pestos’ paste consistency? No, not really, he admitted. Same-same here…

If you make your own paint, you can see and feel quite easily when you get to that perfect paste stage, usually reached after a two-step dance of a bit more oil, a bit more pigment… just right! You might not be into this, but the beauty of the DIY approach is that you end up with your paint. A paste with the consistency/texture required for the job at hand—for centuries, the painter’s reward after all that grinding and mulling.

Paint out of a tube is more standardised, although, obviously, most artists wouldn’t want it too oily/liquid, nor too stiff/dry for that matter. Still, the ‘perfect’ consistency doesn’t exist, and every paintmaker makes a choice of where that CPVC sits for each of the pigments he works with, at the size he has chosen to grind them, and in each binder of course, as their delightful idiosyncrasies will actually mean a different recipe per pigment, per size and per binder is needed. And that’s where the chef gets to make a difference! “Each recipe is as natural and true as possible, made with a ‘lighter touch’ to preserve and reveal the beauty of individual pigments,” says Cranfield, a British oil paint maker, adding that “It’s the alchemy of Artist’s Oil manufacture: the higher pigment content, the further milling and ‘sweating’ of each batch that shows each pigment in its true colour.”1 For David Coles, master paintmaker at Langridge, paints under his formulations are “following my philosophy of what the paint should be… which is not only, obviously, the highest pigment load possible so that the artists can get as much colour out of that paint as possible, but also that it has a certain feel. That the paint is going to be reflective and honest about the way the pigment actually is and creates certain qualities. You have some colours that are naturally soft and quite fluid. Some which are quite buttery. Some are quite stiff, some clotted. It’s the pigments’ action upon the vehicle used creating that.”2 Robert Gamblin sums it up beautifully: “[A color] reaches its maximum when the pigment has been developed to the highest emotional resonance for that color.”3 And look, I don’t know about you, but if we’re going to wax lyrical about a CPVC, how about swapping it for HER, i.e. Highest Emotional Resonance… much more poetic, in my opinion!

You must also understand that pigments and oil have a long-standing love affair, a natural affinity and desire for one another. (Most of them are just that: lipophilic!) When it comes to water, however… it’s another story. In fact, quite a few of these kids are totally hydrophobic. Literally. Add water. Admire layer of water on pigment. Wait (hours or days, if you will.) Admire that water again. So pretty on top. Mix and enjoy the clotted goo. And you haven’t even added your binder…

The same above-mentioned oil-thirsty Lamp Black pigment will quite refuse your offer of a glass of water, for example. To coax it into accepting it anyway, should you wish to make ink from it, sweeten its beverage! Add some gum Arabic (a trick the Egyptians had already discovered) and the sugar molecules will attach themselves to the fine particles, keep them apart and prevent the clustering.

On the other hand, should you dream of making your own acrylic paint from scratch, trust me, don’t. (Especially not with modern pigments, which are on the whole incredibly fine and love to agglomerate.) Dispersing some of these pigments in water, which is the first step, can take up to 10 takes of shear force on a triple roll mill at Golden’s factory, while Art Guerra uses a bomb mill to produce his pigment dispersions. At a certain speed, the hard ceramic ball-bombs cascade on the side of the mixing bowl, then hit the pigment and eventually tear apart the clumps of aggregating particles. Sometimes it takes 8 hours of this treatment, sometimes up to 5 days if you play with extremely fine particles. Wetting agents help as they create little hooks around the pigments, which the binder can attach to. While dispersing agents help, too, but in a different way. They are a wetting agent of sorts but also act as a suspending agent, basically making the whole dispersion happen. Art makes his own agents but admits that it’s difficult industrial chemistry: “We’ve really suffered on that one” is his take on that stage of the process.

Sometimes it gets even worse, and these rebels become real trouble with all of the above not even enough to disperse them. That’s when they discover the special grinding or acidifying treatment during manufacturing or immediately after. As I said, pigments happy to be here? I don’t really think so. But at least, when that process is over, pigments have been so tamed that accepting the polymer medium you want them in, usually only takes one more mill pass. Or yourself churning the dispersion into the binder of your choice.

You might have wondered why you would want to first disperse the pigment in water. Because you need that water in your acrylic paint anyway and because, apparently, if you add your binder first, there is a good chance it will turn into a cottage cheese of the lumpiest variety… Even worse than clotted goo!

Jump to the next section of the book by clicking here

Alternatively click on the Table of Contents to browse the sections.

You can also subscribe to my blog at the bottom of this page,

and you’ll receive Hues in Tubes in your inbox… as it gets published!

Additional information and references

- From The Cranfield website [Online]. [Accessed 2 February 2025]. Available at: https://www.cranfield-colours.co.uk ↩︎

- From my interview with David Coles. [Online]. [Accessed 2 February 2025]. Available at: https://inbedwithmonalisa.com/2017/05/26/in-bed-with-master-paint-maker-david-coles/ ↩︎

- Interview with Robert Gamblin [Online]. [Accessed 2 February 2025]. Available at: https://www.jacksonsart.com/blog/2014/04/09/gamblin-oil-colours-painting-med ↩︎

Discover more from in bed with mona lisa

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

One Comment Add yours