WHICH?

Pigment Characteristics

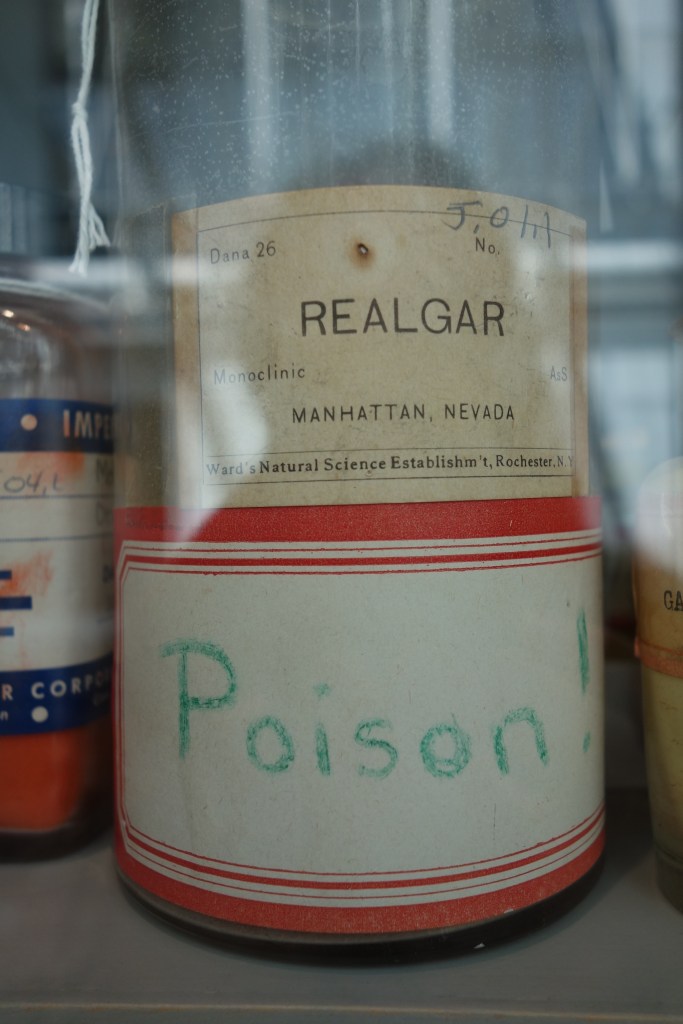

Some pigments are toxic, even today, and when I mocked requests for “natural” pigments, I honestly didn’t mean to trivialise the efforts of those who carefully advise us that Cadmiums, Cobalts or lead-based paints can be dangerous to ingest—possibly even to touch. If paints based on these pigments are still around, despite their shortcomings, again, it’s because they possess unrivalled qualities. However, generations of painters have manipulated them and much worse ingredients on their palettes without dying prematurely, so proper caution and care should do the trick. (It must also be added that these chemicals are very low-risk when sealed within a pigment particle because of their insolubility.) If they freak you out or you have a tendency to chew your paintbrushes, simply opt out. In my opinion, though, there are probably more risks involved in inhaling pigments if you play with these in their powder form, and certainly a lot more yet in inhaling invisible or dangerous substances in varnishes and solvents than from anything contained in a tube of paint.

If I were cheeky again (I am!), I would now mention the annoying: “This product contains a chemical known to the State of California to cause cancer”, which worries and confuses people more than it helps, I believe, while, too, seemingly implying California knows something other states and countries don’t. What they have in Cal. are stricter labelling laws than anywhere on the planet, and chemicals on their Prop 65 List (including cobalt, nickel compounds, cadmium compounds, carbon black, chromium, lead and crystalline silica) require that mention—whether there is any real risk linked to the use of the product or not. We are talking more than 2.5 parts per million cadmium or 10 parts per million lead, for example, so you’re probably much more at risk drinking a glass of tap water in Flint, Michigan, or merely breathing in Beijing on any given day than using any of the products with the warning—but of course, companies have to protect themselves too!

Shifting the risks from you to the environment, please be wary of polluting your wastewater with heavy metals and use rags to dispose of leftover paint safely. Also, even if you are not using these pigments but using acrylic paint, do wipe off your brushes, palette, etc., before you wash them, as plastic down the drain is not a great idea either. If an option where you live, you can even decant your happy mess at the end of the day in buckets and later throw these dry plastic ‘cakes’ in the recycling bin.

You might also choose to eliminate some colours entirely on environmental grounds. Any massive disruption of soil is really not a good idea as, in truth, “green extractivism” does not, cannot exist. It’s sadly only extractivism with the word green in front, a linguistic lure from the mining industries, the World Bank, etc. You might be compelled, too, on humanitarian grounds. According to the UNICEF, around 40 000 girls and boys work in ‘illegal’ cobalt mines in the southeast of the Democratic Republic of Congo. Earning a pittance, these young ones put their lives and health at risk every day. I know this cobalt is destined for lithium batteries, electric cars, etc., not a ravishing blue or teal on our palettes or in such tiny amounts that it would hardly create such situations, but the reality is there: nothing much has changed from the time men were slaving away in the Almadén Cinnabar mines or workers suffering from the acute symptoms of lead poisoning.

Now, as for the pigments you can eat, perhaps even should eat regularly? You can eat/drink cochineal and probably do so more often than you realise, as this powerful natural colourant is used in many cocktails, lollies, sauces, cakes, ice creams, etc. But even if harmless, it’s tasteless, and really no reason one should eat it… except with the eyes. In truth, only a few I know of fit the should.

Zinc supplements can be a good idea (the same can be said of it as sunscreen.) But, far more exciting… are you old enough to remember that black mouthful of crunchy granules with a slight vanilla taste? It was given to me back then for all stomach aches and worked fantastically well (just sticking your tongue out in the mirror already made you feel better) but seems to have been altogether forgotten… only to reappear recently, having graduated from digestive remedy to super-effective internal detox agent + teeth brightener + facial mask + + + = meet our humble charcoal, now fully ‘activated’ of course! (Not being the girl to shy away from the call of duty and in-depth research, I actually bought some activated charcoal toothpaste. Spitting black is… weird! (Such is our relationship with black and white; it feels dirty, not clean.) But the biggest shock came a few days later, when seeing myself accidentally in the mirror turned into an Ohaguro geisha!

While we’re on activated charcoal, you might remember me mentioning a pigment called Peach Black. I’ve also just reminded you of the dangers of breathing in your pigment powder. Well, this one is different. Produced from the calcination of peach stones, the pigment is virtually non-existent nowadays in art stores—even if the name still lingers on some paint tubes. No paintmaking in view then, so what were all these young American ladies doing proudly on that pile of pits? A serious contribution to the war effort, that’s what!

Possibly the worse on the list of WWI’s horrid inventions was the practice introduced by the Germans of releasing chlorine gas in the direction of their enemies. (A practice promptly used by the other side, too, it must be added.) When the wind was in their favour, the invisible gas would infiltrate the trenches and lungs, killing the men in exactly four breaths. Trained to hold their breaths for six while adjusting their face masks, it was nevertheless not the mask that saved soldiers even if it pinched their noses. Forced to use their mouthpieces only, the air—which passed through a chamber of activated charcoal mixed with other anti-gas chemicals—would then enter free of poison into their lungs. And so it came to be that a pigment saved the lives of thousands. Of course, other pits could be used, but peach stones, certainly from one day to the next in incredible demand, seem to have become the rallying cry of both Red Cross and Government. “Throwing your peach stones away is like throwing the lives of our soldiers” or “Do your bit – Save your pit” posters flourished while patriotic collections were organised everywhere by the women and children of the U.S.A.

My second example of ‘good’ pigment (in fact, a diversity of Earth pigments) is far more ancien, and had over sixty references in the Hippocratic corpus. Descriptions of their respective medicinal virtues followed, the most reputable one being a specific red clay found on Lemnos. The Greek island was then known as the homeland of the Amazons and where the god of fire and volcanoes, Hephaestus, landed after being hurled from Mt Olympus by his father, Zeus. Unfortunately for us all, Hephaestus survived and would eventually open Pandora’s box and be responsible for all our earthly miseries but—maybe a slight redeeming factor?—the place he fell on this island was also the alleged source of this Sacred Earth.

Whether they even believed the story at the time or not, what is certain is that the therapeutic Lemnian Earth was held in high esteem by all the famous physicians of Antiquity who recommended it both for internal and external uses and for a variety of ailments, including as an antidote to viper bites and poison. When needed and “coming in contact with liquid, [the tablet] immediately dissolves and becomes clay.”1 As a result, the dried clay was shipped all over in the form of little tablets stamped with a seal bearing the sacrificial symbol of the goddess Artemis, the goat. Why was her well-known chastity, hunting skills and connection to the moon chosen as symbols for our first-ever pills and not something relating to our brave Asclepius, god of medicine and patrons of doctors? Only the gods know the answer to that one, but it must have been a good marketing idea as this sealed ‘trademark’ and the popularity of Lemnos’ terra sigillata never ceased. Yet, where once Hellenic priestesses had been in charge of the yearly ritual of collecting, washing the clay and blessing the dried tablets, later the seal was changed to the Grand Efendi’s one (as witnessed by Jacopo Salerno, emissary of Venice to the Ottoman Sultan in 1581) before receiving the Christian blessings of the local clergy until the end of the 19th century when production stopped.

Such was Lemnian Earth’s reputation—it could even prevent the plague!—that many fakes circulated on markets in the East and Western Europe from the 16th to the 19th centuries. This is a shame because there is no way for us to analyse with certainty a genuine Lemnian pill, despite some tablets still being around. Nevertheless, field research, doctors’ testimonies of its benefits and eye-witnessed written accounts over the centuries seem to point to what was so special about it. Clay is known to absorb toxins, dry wounds and soothe inflammations, but the (estimated) combination of 40% montmorillonite, 35% kaolin, 20% alum and 5% hematite present in Lemnian clay apparently gave it, on top of these properties, particularly potent anti-bacterial ones. What is fascinating about this composite “pigment”2 is that it was not just found in nature ready-made. (Sorry, Hephaestus but it seems us mortals also had a hand in it!) The sacred earth was the result of a rather banal pit of clay—undoubtedly suitable for potting and maybe rich enough in montmorillonite to provide a good fabric detergent—being filled up intentionally with the waters of a nearby spring, diverted for a few months of the year, and which seems to have been rich in alum. Absorbed by the clay, alum’s astringent and haemostat properties would have added the final curative ingredient. Many accounts also remark on the different qualities extracted. The red clay, the uppermost one, was of higher symbolic value and deemed superior quality.3 The effect of its colour increasing, no doubt, its potency: placebo or richer iron content is up to you to decide.

Nowadays, maybe only a “Communion with the Earth” workshop might require ochre ingestion because if clays are still used externally for face masks or cleansing purposes, internal use seems to have few followers and is suggested only in rather alternative medicine. Yet there are some serious studies that, combined with seafood, red ochre boosted early humans’ supply of docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), iodine, and, potentially, iron and other nutrients essential for brain development. Furthermore, adding some iron supplements to your diet when pregnant or suffering from anaemia is just the thing isn’t it? Other researchers dismiss these theories but nevertheless acknowledge that geophagy, aka intentionally consuming earth, is a well-recognised practice in many cultures whose people ingest specific soils medicinally to prevent diarrhoea or increase iron intake. Geophagy might not be your cup of tea much but now you know… there should be no harm in tasting a little red ochre from time to time, either!

P.S. Just sharing one recipe I came across, which really appealed to me. Easy too. Cover your freshly caught fish with coarse sea salt and red ochre, then marinate. Fishermen on the Iranian island of Hormuz say this Sooragh is a grilled delicacy that “combines not only the taste of the soil and fish but also the soul of our beloved island.” Perhaps worth a try with some ochre from your favourite spot?4

P.P.S. Make sure it’s ochre, OK?

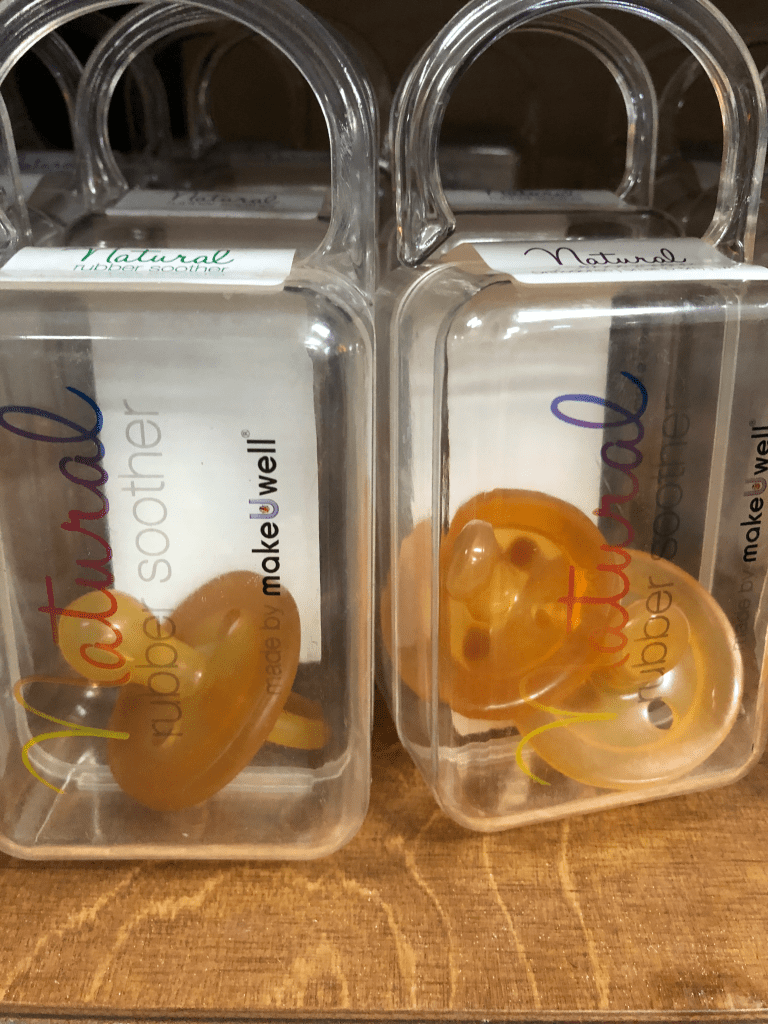

P.P.P.S. Ochre is so safe that it was used for a long time as a firming agent to natural latex—which is very runny. This also explains why our rubber rings around jars were orange! Today, the formula has been revived for natural baby pacifiers, but not much more I know of. Nevertheless, I must point out that eating ochre before processing it is not a good idea! In the Roussillon ochre mines, I understood that, before digging a new tunnel at great human expense, they would have someone ‘taste’ the ochre. (Less than 20% ochre to sand was not worth the effort, and, it seems, women were better tasters than men. Unfortunately for them, swallowing large amounts of sand (the other 80%) is not an excellent idea for the gut!)

Jump to the next section of the book by clicking here

Alternatively click on the Table of Contents to browse the sections.

You can also subscribe to my blog at the bottom of this page,

and you’ll receive Hues in Tubes in your inbox… as it gets published!

Additional information and references

- Pliny the Elder, The Natural History [Online]. [Accessed 2 March 2021]. Available at: https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/textdoc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.02.0137%3Abook%3D35%3Achapter%3D14 ↩︎

- Spyros Retsas, Geotherapeutics: the medicinal use of earths, minerals and metals from antiquity to the twenty-first century, 2016. [Online]. [Accessed 2 February 2025]. Available at: https://www.lyellcollection.org/doi/abs/10.1144/sp452.5 ↩︎

- Ha, but you might ask, are clays and pigments the same thing? The ones that do count as ochres are in fact hard to define as that term does not correspond to a precise mineral and has widely varied over the centuries. Moreover, you can both read that ochres are clays, which take their colour from iron oxides, as well as iron oxides found in clayey soils, which is not quite the same thing. ↩︎

- For more recipes go to: https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/red-soil-gelak-hormuz-rainbow-island ↩︎

Discover more from in bed with mona lisa

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Another informative and entertaining read – thanks for posting!

Reading about Kanemizu there, I was reminded of traditional iron gall inks (still around, though in less acidic forms for modern fountain pens), with the iron and oak gall tannic acids (as in tea above) oxidising on the page to a dark black some time after writing with it.

And as for “carbonated” toothpaste – I’d never heard of it until I inadvertantly bought a tube of typical-looking Colgate on a recent holiday to Portugal. Once I opened it though, I was horrified to see it was black! Thankfully, once it’s brushed on, it reverts to a familiar white froth, and avoids any involuntary gagging reflex.

Thanks for all your comments on my posts! It’s truly fun for me to get feedback and your stories are great too! Coming soon is the story behind all the names of paints/pigments and you should enjoy that (I’m hoping!) all the best Sabine