HOW?

At last (and thanks for your patience)… Paintmaking!!

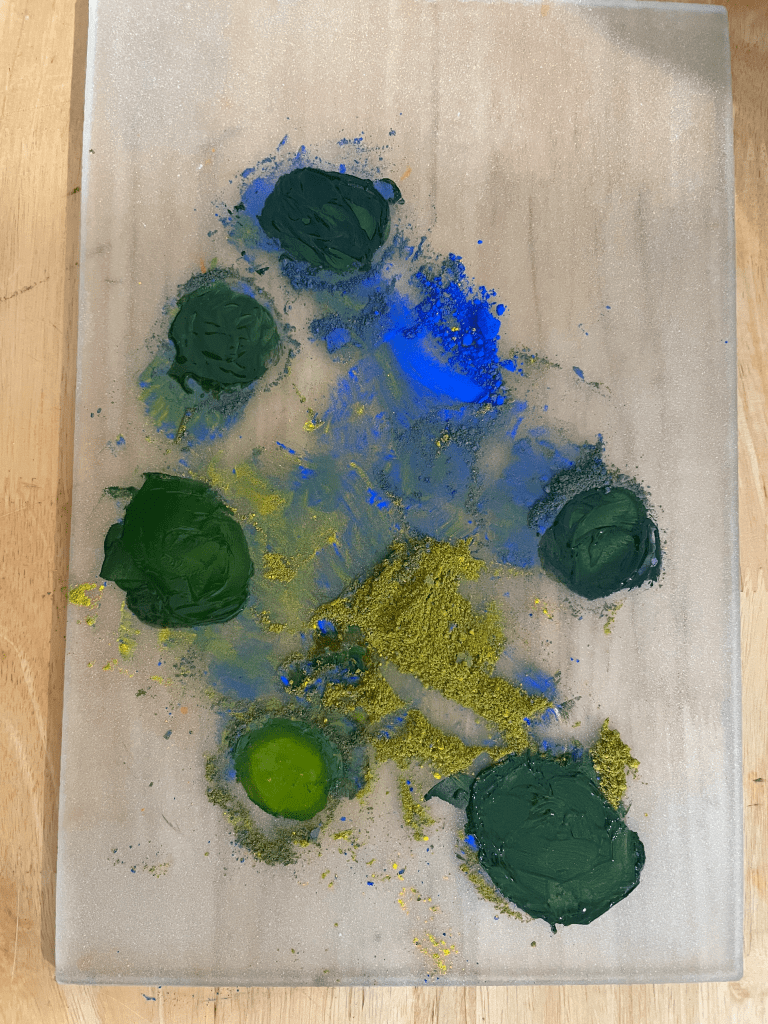

Whether you buy your pigments in an art store or produce them yourself, making paint by hand is definitely an option, especially with certain binders, and, in my opinion, one of the most satisfying steps is actually pre-mixing your pigments. As the title of a good book on colour mixing, Blue and Yellow Don’t Make Green1, challengingly (daringly?) emphasises, mixing blue and yellow paints will only give you a ‘sensation’ of green, not ‘really’ green. It’s hard to belive, I know, but I’ve noticed how mixing pigments rather than paints makes that so much easier to understand.2 It might not do the trick for you, but it makes the obvious more obvious to me.

I would give oil a go any day, it’s so sexy yet straightforward. Premix on an etched slab of glass (which helps pull apart the particles) a little oil3 in your pigment with a palette knife, then mill it with a dedicated muller, also sandblasted to create a fine tooth. Add more oil and repeat. Nothing dries. You can take your time until you reach the consistency you like, so that’s a bonus. That’s the theory, and it does work for most pigments, but (as we’ve already heavily hinted at) not all are happy to be turned into paint, and these have a trick up their sleeve to let you know. Ultramarine, for example, will rapidly turn into this seemingly perfect paste, but if you turn your back, come back a couple of hours later, it has separated and returned to a liquid state. Add more pigment… mill… wait… repeat. Add oil to Alizarin Crimson, on the other hand, follow the recipe and admire how nothing happens, no paste. Add more oil, repeat and…. repeat and…. repeat! When you cannot blend no more to save your life, give up and decide it’s a good enough paint paste. (If you’re the sort of cook who likes to follow a recipe, take notes of your process with each pigment, but if, like most creatives, you’re actually quite annoyed by them, I’d say that’s fine, there really are too many variables, make paint by observation and stop when the sauce is to your taste!)4

(If the videos don’t work in your email please go to my website.)

Whenever that time comes, for all the paints you have been making, mind you, and however much heart and elbow grease you’ll have put into the milling, I sadly have to inform you that your paint still won’t compete with the perfection of paint after a trip in the triple mill roll. (They even say a hand can only do half the job!) There, the heavy rolls tightened at every pass of the paint, will literally tear apart any pigment cluster left after the premixing—usually performed in large blenders—and ensure all and every facet of every micro-particle is coated with the binder in a way you couldn’t ever. In the profession, that step in the production is often called grinding, yet neither muller nor mill alters the particle in any way, shape or size. That grinding has happened before it all started. What happens under the muller is milling, coating, mixing, blending, and, confusingly, you can call it grinding, too, as one of its meanings is “the action of rubbing things together gratingly” but understand this stage does not alter your pigment size anymore.

Tempera paint is also an easy one to make. There are many variations on this emulsion recipe, sometimes using the whole egg, only the white, only the yolk, sometimes some oil is added, and sometimes it’s even emulsified in beeswax. The simplest? Crack an egg, discard the white, remove the little membrane over the yellow, and store the yoke obtained in a drop bottle. Mix a little pigment with water in a shallow dish, then add the egg to taste. As mentioned, many criteria over the centuries have been found for choosing those eggs over these eggs, yet freshness seems to really be the number one. Freshness of paint, once made, was/is a problematic issue too. Make too little, and you must repeat the procedure; make too much, and over the next few days, your egg starts to rot and stink!

The other waterborne paints know similar problems. If it’s also pretty straightforward to make your own watercolour or gouache with gum Arabic and the addition of glycerine/honey to improve handling, don’t forget, however, if you wish to store them, to add a drop or two of preservative, an anti-mould agent of a kind or another—clove oil is a good one for home-made paint but not sure it will be enough to deter the mice… Often, I found that little nibbles had been taken from a pan in my store, and a client even shared that she had found multi-coloured droppings next to her paint box!

For gouache, add blanc fixe, whiting chalk or some white pigment as a load to give the paint opacity and, in all cases, first create the aqueous dispersion before adding the other ingredients. As we have seen earlier, when pigments are hydrophobic, that’s the hard part. These and a few pigments with very fine particles sometimes can benefit from adding a dispersant, such as ox gall, but may your wrist be light because too much dispersant and your paint, later, will go on dispersing like crazy, which is hardly desirable.

As mentioned earlier, I would not suggest you make acrylic paint from scratch and for a simple reason: quantity. Tempera is a leaner paint. And despite there being a painting technique called “petit lac”, which consists of making little pools of colour which, when joined, create a large flat area, usually, due to its non-flexible nature, egg tempera will only allow short strokes and no kind of impasto or gesture that would require a considerable amount of colour. The quantity of watercolour and gouache paint you use is up to you (and a bit more the better, as we’ve seen), yet they don’t come in the smallest tubes on the market for nothing, as these paints go a long way. In all these aqueous paints, and maybe for different reasons, you will usually make small batches, which implies processing only so much pigment in water. But, even if you are a lean artist, in acrylic, let’s face it, you’ll usually work larger, make bigger strokes, and waste some which has dried; in short need much more paint.

And that’s when things get a bit trickier. Even putting aside pigment dispersion issues, as you could buy ready-made ones, we are still left with a range of options and problems inherent to polymer emulsions (including the fact they dry so damn fast!) that make the whole thing just a notch or two more complicated than deciding on the colour of the egg.

I once had the privilege of visiting the Golden factory and chatting with Jim Hayes, director of the lab and Master Chef there, I had asked him for their recipe. He seemed a bit thrown back by what appeared to him an obvious thing, but kindly walked me through it all. (Acrylics suitable for artists are not old, and the original polymer emulsion only goes back to 1953. Paint at first cracked, hardened, moulded, stank and dried, and so endless trial and error, formulating, reformulating, adding a touch more of this, less of that, has been required to achieve the suave paint we now know. Quite a process in truth, and one I personally don’t feel the need to repeat in my studio at all, but then you might be more adventurous than I. Acrylics have come a long way since Sam Golden’s pioneering years, but the attitude in that excellent factory has been the same all along. Not just aiming for good paint, but an exceptional one, which will still be around in five centuries and… so far, so good!)

Vinyl and acrylic paint may not reflect the ‘personality’ of the person who creates it as much as oil paint does, but you need to get your formula spot on. And let me tell you, it’s a careful balance of requirements and ingredients that will make a happy paint. Too much of this, and that happens; too little of this, and that happens. At Golden, the recipes have been perfected; for every colour/binder, it’s an elaborate and distinct one. (Not only because each pigment is different but because Golden produces, in virtually every colour, up to 5 different viscosities of paint: heavy body, matte heavy body, slow drying, fluid and high flow.) If you’re game for a big batch, you will find here the ingredients and the steps.

Obviously, while I talk of recipes, paintmakers would probably talk of formulations, and yet there is something about a colour plant that always reminds me of a kitchen. Yes, the food processor is enormous, the spoons, scoops, ladles and icing knives would probably be best suited for the production of a Gargantuan cake and the pasta machine big enough to churn out lasagne for the entire Roman army (that’s the triple mill roll by the way) but should you downsize the whole affair, all the implements needed to make paint would look perfectly normal in your home.

Nevertheless, as you probably won’t invest in a triple-mill roll, your paintmaking setup will differ significantly from theirs. In a corner, you might have a few decanting jars and a pestle and mortar if you process some raw pigments from scratch. In another, probably no more than a muller and a slab on a sturdy table and the few ingredients needed to make your paint. (Don’t forget the mask! Especially if you intend to play with historical pigments such as Verdigris, Lead White, Vermillion, etc. But all dry pigments are hazardous and should not be inhaled.) Muller, slab, pigments, pigment dispersions, if you feel inclined (not as common, but they can be ordered), and all mediums are usually available in good art stores. Some ready-made binders for gouache, watercolour, casein, etc., with all the necessary additives, also exist. (These are great, if a bit of a cheat, and will save you no money but a fair bit of time if you are making paint… to paint with.) You can also reinvent the wheel and your own recipe(s). You will need a bit of patience and wrist grease too, but the exhilaration of actually making your paint is beyond belief, and, mostly, especially if you want to use your colour fresh, you should be fine.

PS: I feel like adding one more thing: Don’t do it to save money! Rudolph Ackermann, author and colourman, wrote back in 1801: “The time, the trouble, the expense attending their preparation will never compensate the small saving gained by it”, and nothing much has changed there. Do it for technical reasons, if you will. I know an artist who usually paints a series of large canvases with the same background colour. He premixes the colour of his choice using pigments and an acrylic binder, then undercoats all his canvases at once—using his whole batch of paint… fresh! (You could also premix your pigments and keep that mix for future use.) Yes, it saves him money because he needs a considerable quantity of the same colour, but, more so, it makes his life easier, giving him the consistency he craves. After that initial burst, he slowly paints his intricate paintings with colours out of branded tubes.

PPS This is a disclaimer that IF you catch the pigment/paintmaking virus, as many do, your studio/garage/kitchen might soon look not so pristine, not even like an industrial kitchen but more like an alchemist’s den with shelves cluttered with vials, tubes, jars, ‘interesting’ plastic bags filled with… ?? Probably bits of planet dreaming/decanting and a few other most useful and precious items (in your eyes at least), BUT that none of this is my fault… blame them irresistible and colourful beauties!

Jump to the next section of the book by clicking here

Alternatively click on the Table of Contents to browse the sections.

You can also subscribe to my blog at the bottom of this page,

and you’ll receive Hues in Tubes in your inbox… as it gets published!

Additional information and references

- Wilcox, M. (2001) Blue and Yellow Don’t Make Green, How to mix the colour you really want want—every time. Second Edition. School of Colour Publications, Bristol, UK ↩︎

- May I remind you that mixing two pigments rather than going for a monopigmented (green in this case) pigment will, in the material/subtractive Colour world, ‘substract’, precisely, more colour and that, should you continue adding more pigments it will turn the whole thing into a muddy/muted mess quite quickly. ↩︎

- All that is needed for oil paint are those two ingredients. You can choose your oil. A variation on linseed oil is usual, while some companies swear that poppy seed, walnut or safflower oil should be used for the lighter colours as these are less yellowing. But, let’s face it, all oils yellow somewhat eventually, so not entirely sure it makes such a difference, and neither makes as strong a paint film as linseed. (I’ve witnessed once Flake White paint being made with walnut oil. How it slips off the last roll of the mill and down the chute… must be pretty unusual to paint with that one!) ↩︎

- I am only giving you, here, basic recipes. There are others involving casein, gum Arabic, etc., and you can find some in the remarkable book by Michael Price, Renaissance Mysteries, Vol I: Natural Colours, Michael Price Inc, New York, NY, U.S.A. There, you will also find recipes for specific historical pigments, such as Azurite, Cinnabar, or Lapis…There are othersbooks but I can recommend these below specifically about pigment making and paint making

Delamare, F. ( 2000) Colour: Making and Using Dyes and Pigments. London: Thames and Hudson

Gustafson, H. (2023) Book of Earth: A Guide to Ochre, Pigment, and Raw Colour. Abrams, New York, NY, U.S.A.

Kremer Pigmente Recipe Book (2023), is a self-published paintmaking recipe book by the German Pigment company Kremer, which you can order on their website: https://www.kremer-pigmente.com/en/shop/books-color-charts/english-books/992101-kremer-pigmente-recipe-book.html

Logan, J. (2018) Make Ink: A Forager’s Guide to Natural Inkmaking. Abrams, New York, NY, U.S.A.

Mayes, L. (2025) The Natural Pigment Handbook, A Maker’s Guide to the Art, Stories and Recipes for Creating Paint.

Ross, C. (2023) Found and Ground: A practical guide to making your own foraged paints. Search Press, Tunbridge Wells, UK

Webster, S. (2012) Earthen Pigments: Hand-Gathering Natural Colours in Art. Schiffer Publishing Ltd, Atglen, PA, U.S.A. ↩︎

Discover more from in bed with mona lisa

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

I learn a lot from you!

super glad to hear that!!!