WHYEVER?

Hues in Tubes… and how they made a name for themselves

Should I, before we get sidetracked, state the obvious? Never a great idea but the title of this book being what it is, I must at least clarify that there were many centuries in which, obviously, hues were not in tubes. For that to happen, first a

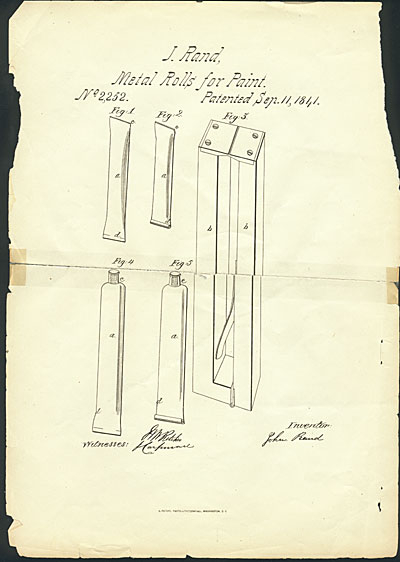

“metallic vessel [had to be] so constructed, as to collapse with slight pressure and thus force out the paint or fluid confined therein through proper openings for that purpose and which openings may be afterwards closed airtight, and thus preserving the paint or other fluid remaining in the vessel from being injuriously acted on by the atmosphere.”1

We owe the above description, and the invention of the mighty collapsible tube, to John Rand, an American painter—even if a few adjustments were subsequently made to this initial 1841 patent which consisted of a mere hollow tin cylinder crimped on both ends. The idea came to him from his frustration at learning from his tutor nothing else, it seemed, than how to mull pigments in oils.

For millennia, shells were used as virtually indestructible, readily available vessels for pigment paste to the point that it seems unclear if paint could have existed without them! It is rare, perhaps unique, for the container of a material—something used only for the practical purpose of preparing, carrying, and storing—to be the reason we know about and can trace the presence of that material.

One of the two abalone shells containing an ochre-rich mixture that were found at Blombos Cave in Capetown, South Africa. c.100,000B.C.E.

And, yet, this is the case in the Blombos caves as, if it was not for the shell in which it was made, what would be left? Grains of red earth pigment, perhaps surprising in a place that does not have red ochre, or, most likely, nothing. Just dust returned to dust, a bit of red earth mixed with other soil, buried and compacted by millennia. But paint paste we did find, in abalone shells, and it helps us connect with our ancestors in such a meaningful way that we should have immense gratitude for that vessel, consider it a ‘treasure’ on par with its contents.

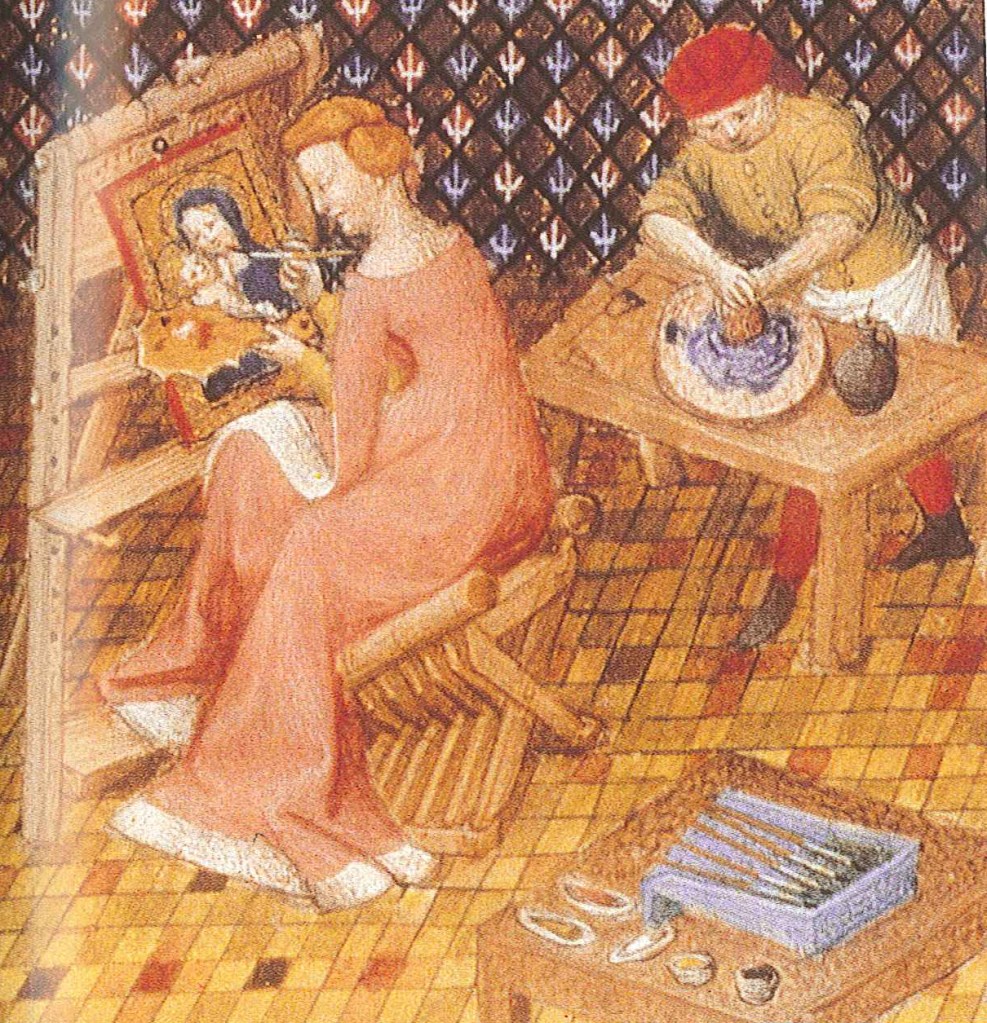

Maitre du Couronnement de la Vierge, Timarété painting, c.1403. Miniature from Boccace’s Livre des Clères Femmes, Fr.12420. Bibliothéque Nationale de France, Paris, France.

We still come across sweet cockle or mussel ‘pans’ from the Victorian era holding watercolours, similar to the clam ones on a table near this Medieval artist. (Would you believe there’s even a species of medium-sized freshwater mussel called Unio pictorum, aka the painter’s mussel?) Amusingly, even more sophisticated pigment holders sometimes imitated shell shapes. One can admire, for example, an Egyptian pigment holder carved in ivory in the form of a hand holding a stylised mussel at the Boston Fine Arts Museum.

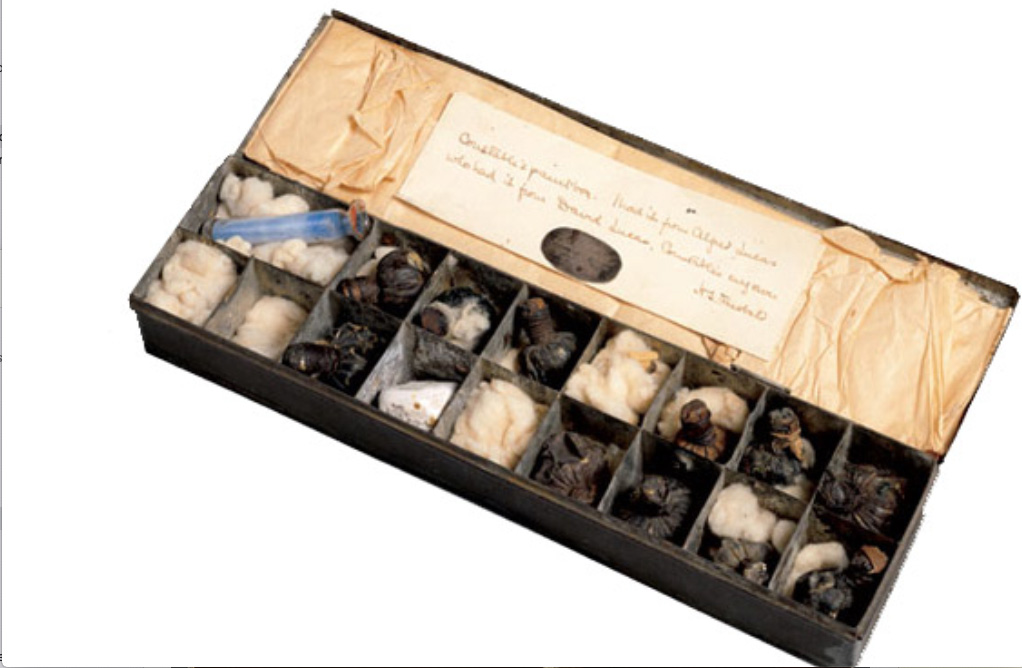

However, and even if all of these containers were doing their job well enough for water-borne mediums, when it came to the more tacky oil paint—which does not dry but oxidises when in contact with air—what was found most appropriate were little pockets of pig’s bladder skins sealed with a knot…. a sausage of sorts! (A spike bone stopper could pierce the skin and act as a plug when needed.) The whole business was a messy one “[…] a bladder of Prussian Blue bursts over one’s arms, and paints one’s fingers and cloth”2 complains one artist, while all of them could have concurred that paint, stored thus, had a tendency to grow fat and unusable which, in truth, did not entice making big batches of paint, hence the endless mulling!

Constable’s metal paint box containing eleven paint bladders, a piece of white stone and a glass phial of blue pigment, c.1837. Estate of Sir Edwin A.G. Manton, Tate Britain, London, UK

Although painters understood quite a few laws of perspective, physics, optics, etc. way before any of these disciplines even existed, Rand’s tube was most probably sadly the first and maybe only time the visual arts would provide a technical invention to become a bestseller in all fields, from tomato paste to toothpaste when, usually, it had been Industry which had needed, researched and developed new techniques for their much more vital and lucrative businesses. Fine art paintmaking was and still is today a minute part of the Colour industry. Think cosmetics, printing inks, textile dyes, ceramics glazes, paints for homes, cars, the Eiffel Tower, etc., and you can quickly grasp that artists’ demands and specific needs for colours usable in their trade are of negligible commercial significance. In reverse, however, anytime those industries have devised new tricks and colours, artists—given a chance to improve and widen their palette and options—have adopted them swiftly.

John Singer Sargent, Claude Monet Painting by the Edge of a Wood, 1885. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, U.S.A.

There were two significant consequences to Rand’s invention, whom I hardly think could have imagined what a door he was opening for his fellow painters. For one, that tube turned the whole world into a studio.

“Without colours in tubes, there would have been no Cézanne, no Monet, no Sisley or Pissarro, nothing of what the journalists were to call Impressionism”,3

Renoir allegedly said. And it is certainly true that armed with a few brushes, a fresh canvas and some hues in tubes, painters all of a sudden could take their trade to the brooks and the hills, to the fields and the sunsets, but also to the factories, train stations or the brothels at all hours of the day. In a short time, Light shifted from a meticulously played-with effect into something to be captured and rendered as it danced on the sea or caressed the stones of a cathedral, while official portraits, languid ladies on sofas, angels in baby blue skies and stately Madonnas were replaced as subjects by anonymous dancers in little guinguette restaurants, picnics in the nude (for some), and peasants sleeping on haystacks.

Of course, this idyllic depiction of plein-air (oft painted with variations) doesn’t even begin to represent faithfully how tough it is to paint outdoors… sometimes. In his letters to his brother Theo, van Gogh often complains of being “dusty, always laden like a hedgehog with sticks, easel, canvas and other equipment.”4 But also of being hungry, thirsty and hot, of having to fight off the mosquitoes, and his worst enemy, the fierce Mistral wind which, despite fastening down his easel with pegs, he was powerless to stop his canvas from shaking. Ha! The good people of Arles must have made fun of this red-haired one, returning sunburnt no doubt after his field days, his canvases covered with flies and sand, scratched by branches and brambles… “Only mad dogs and Dutch painters” these must have sneered!

The other unforeseen consequence of the tube revolution was that it freed the painter from making his colours, opening the possibility that the maker of art and the maker of art materials would not be the same and one person anymore. For millennia, every painter would have first been an apprentice in a guild or under the wing of a master. His first years, as Rand promptly discovered, would probably have consisted of many tedious hours of grinding dense chunks of rocks into a powder, of making fresh temperas (the eggs would rot after a few days… hum), of dosing with precision oils and coloured particles.

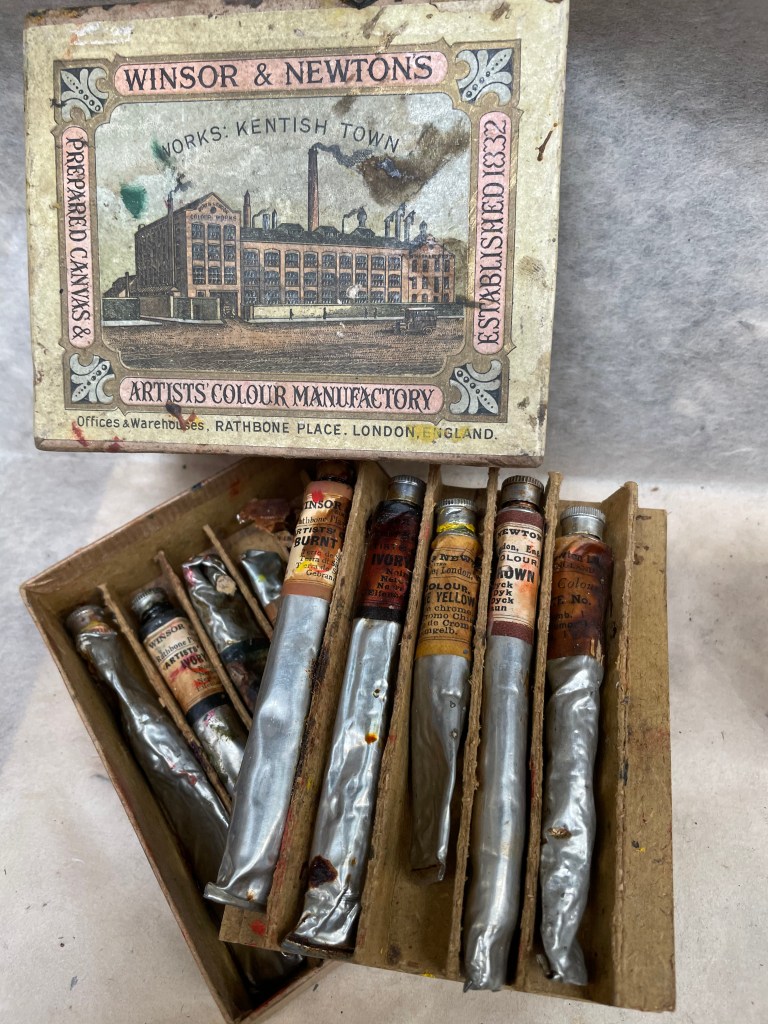

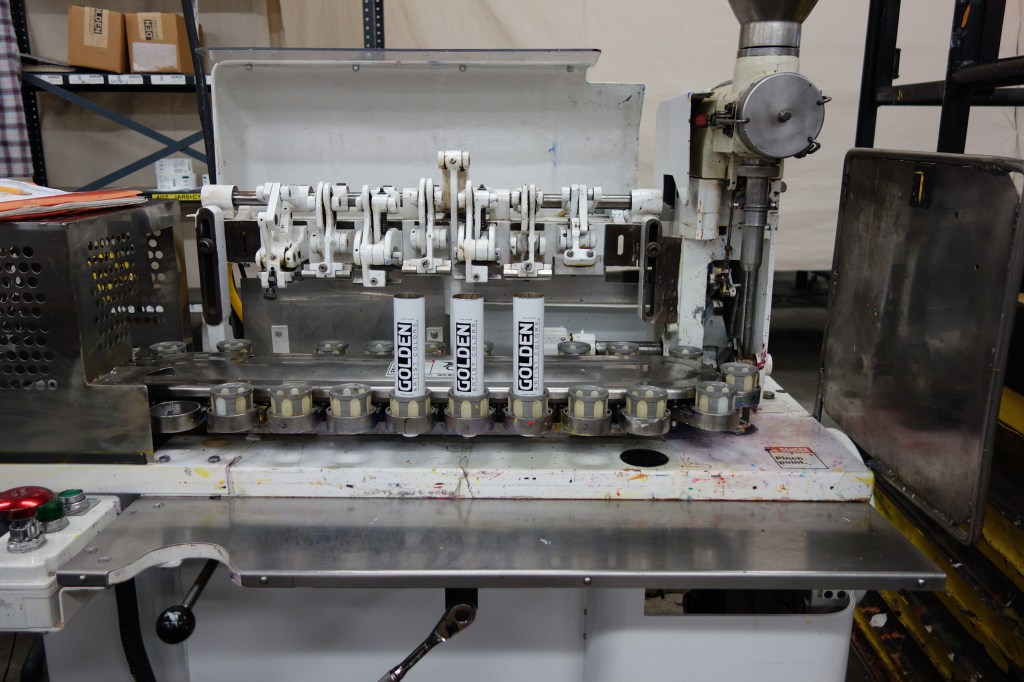

Painting was considered a trade in which both techniques and manufacturing secrets were handed down like treasures. However, nobody could argue that a painter’s primary business is… to paint! And so, as soon as a few companies made it their business to create fine art quality paint, artists only too delighted by the extra time and freedom from the strictly technical side of their work seized the opportunity. These companies, often with a chemist at their helm, became creative in their own right—a trend which seems to have never stopped since— and the times saw incredible improvements in the quality and variety of art materials (some disasters too, it must be admitted!)

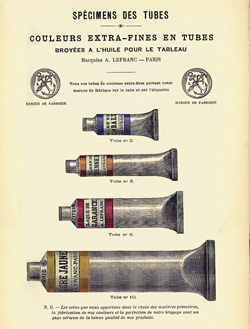

For example, it is Alexandre Lefranc, from the paint company nowadays called Lefranc Bourgeois, who understood tin altered the pigments less and devised the screw cap, giving the tube its ‘other side’ if you will: the shoulder, neck and cap, which can hermetically seal the paint, sometimes so annoyingly so. (But do remember you can always unfold the crimp at the other end and scrape out that last dash of yellow you desperately need in the middle of the night.) However, before Lefranc and Rand’s patent and manufacturing operation, there is proof that some artist colours were already packaged in tubes by Reeves & Son, Rowney & Co. and Roberston & Co. When a good idea is floating in the air, many will sense it, even if they don’t then take full advantage of it.

The dissemination of hard-earned knowledge, previously held by art-chemists/painters, into ready-made paint in tubes and mediums you could buy over the counter must have enticed many a young aspiring artist to try her hand at it. Ladies, at first, seemed to have developed a predilection towards the more gentle watercolours, while oil paint (always the most ‘serious’ one n’est-ce pas?) suited the gents’ temperament better, perhaps? But in truth, and whatever they painted with, paint became more democratic, and that was perhaps Rand’s tube most important contribution (not quite sure what Raphael would have made of Bob Ross or paint-by-numbers, however…)

Still, from that separation into paintmakers and paint users, even if much has been gained for the modern artist, sadly, too, something in the shift has been lost. I often see in the eyes of my clients one of these little ‘lost’ moments when I justify, for example, the difference in price between a series 1 and a series 9 by the cost of the pigment they contain. To some young artists, brought up on being able to add 5% more Cyan with a click, the materiality of the medium seems a little bit strange, perhaps even dated. You mean they don’t just, somehow, pour ‘colour’ into these tubes? As you’ve understood by now… no, they don’t; they put pigments—sometimes expensive ones—a few other ingredients and an enormous amount of know-how.

Eventually, all paints followed suit and jumped into a tube. Gouache and watercolour very happy to be again the “moist” paints that they are when freshly made, but of course, further down the track, acrylics too — which could probably not be sold any other way. Perhaps, though, now that they are safe but hidden from our touch and eyes, the elegant tube has added a layer of remoteness with the material, which doesn’t help? (It also makes life messy in art stores as everyone keeps opening the damn things and, feeling guilty certainly, screws back the caps in a hurry, leaving marks of paint all over and a badly screwed cap to boot!)

This being said, what has much more importantly and per forza vanished is the mystical contact with the ‘pure’ colour of pigments which gave artists not only a reverence for the process and an appreciation of its complexity but also a direct contact with the energy and beauty of the raw hues. This hands-on approach no doubt opened the subtle possibilities pigment grinding could offer in terms of shades. While each stage of the painting and the artist’s personal preferences allowed specific adjustments to be made to the paint texture in the mulling stage, rendering mediums and solvents sold today virtually unnecessary.

Jump to the next section of the book by clicking here

Alternatively click on the Table of Contents to browse the sections.

You can also subscribe to my blog at the bottom of this page,

and you’ll receive Hues in Tubes in your inbox… as it gets published!

Additional information and references

- John Rand’s patent as quoted by Stauter, G.A. (1958) The irrepressible Collapsible Metal Tube. American Perfumer & Aromatics, December, 1958. The Tube Council, Naperville, Illinois, U.S.A. ↩︎

- Quoted by Harley R.D. (1970) Artists’ Pigments c. 1600-1835 A Study in English Documentary Sources, p.65. Butterworths, London, UK ↩︎

- Quoted by his son, Jean Renoir, in Renoir, My Father, 1962. Collins, London. ↩︎

- van Gogh, V., from 22 June/3rd July 1885 in The Complete Letters of Vincent Van Gogh (1991) New York Graphic Society, New York, U.S.A. ↩︎

- “The design of the new vessel and packaging was approached through research with artists and in use testing and feedback. The overall goal was to provide a vessel and packaging design that allowed artists to spend more time painting, and less time figuring out what the product does and behaves like. From a design perspective, we did this by putting the technical information on the front of the packaging and adding a true color swatch so the true representation of the color when dry was seen. From a vessel perspective, we developed a nozzle to best deliver the fluid consistency of the paint – allowing artists control when squeezing out onto a palette, or allowing artists the opportunity to use the nozzle to apply drips and lines to a piece of art. The top of the bottle features a flat, screw-off top to allow for the ability to stack the bottles on each other and optimize precious studio space. The bottle also features an extra wide neck and no shoulders or corners for easier paint access.” Online]. [Accessed 2 March 2025]. Available at: https://www.liquitex.com/row/liquitex-uncapped-acrylic-gouache/

↩︎

Discover more from in bed with mona lisa

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

One Comment Add yours