WHYEVER?

Hues in Tubes… and how they made a name for themselves

Although one understands (hopefully anyway) that the ‘tangible’ pigment names we just saw are only meant to be ‘evocative’ of the lemon or the geranium (i.e. no pips or petals have been used in making the pigment), others, on the other hand, are named after the colour of even more intangible ‘things’, symbols really. As examples, I’ve picked a well-known trio available in any respectable Christian church: blood, gold and the heavens…

Blood can be found, etymologically at least, in Hematite, the most commonly identified iron oxide in red earth pigments—the root hema, from blood in Greek, to be encountered in many other English words. Crush some red ochre (always our collective favourite, yet in this case chosen for its highest iron content), then wet your pigment. I would be surprised if you do not notice a faint smell that reminds you of… now, what is it again? Oh yes, of course… blood! The invisible link is there. Today we have forgotten or discarded what every People has always known, that Gaia, our primary mother, is made of the same stuff as us: iron, oxygen. (And forgotten along the way, too, the very ancient trick of faking menstrual bleeding with a bit of iron-rich… hematite!)

Dust to dust one day, all for sure, but for now, pulsing along those bloodlines, heart to heart! Because if God used some earth, adama, to make ‘man’, She called the one who would walk that Earth, Adam, another Hebrew word, synonymous to but also meaning “to be red.” A good name in truth, as red earth has indeed been our companion since the beginning of wo-man and ever since… Ceremonies, circles, initiations, on our skins and, all the way into the sepulchre, on our bones.

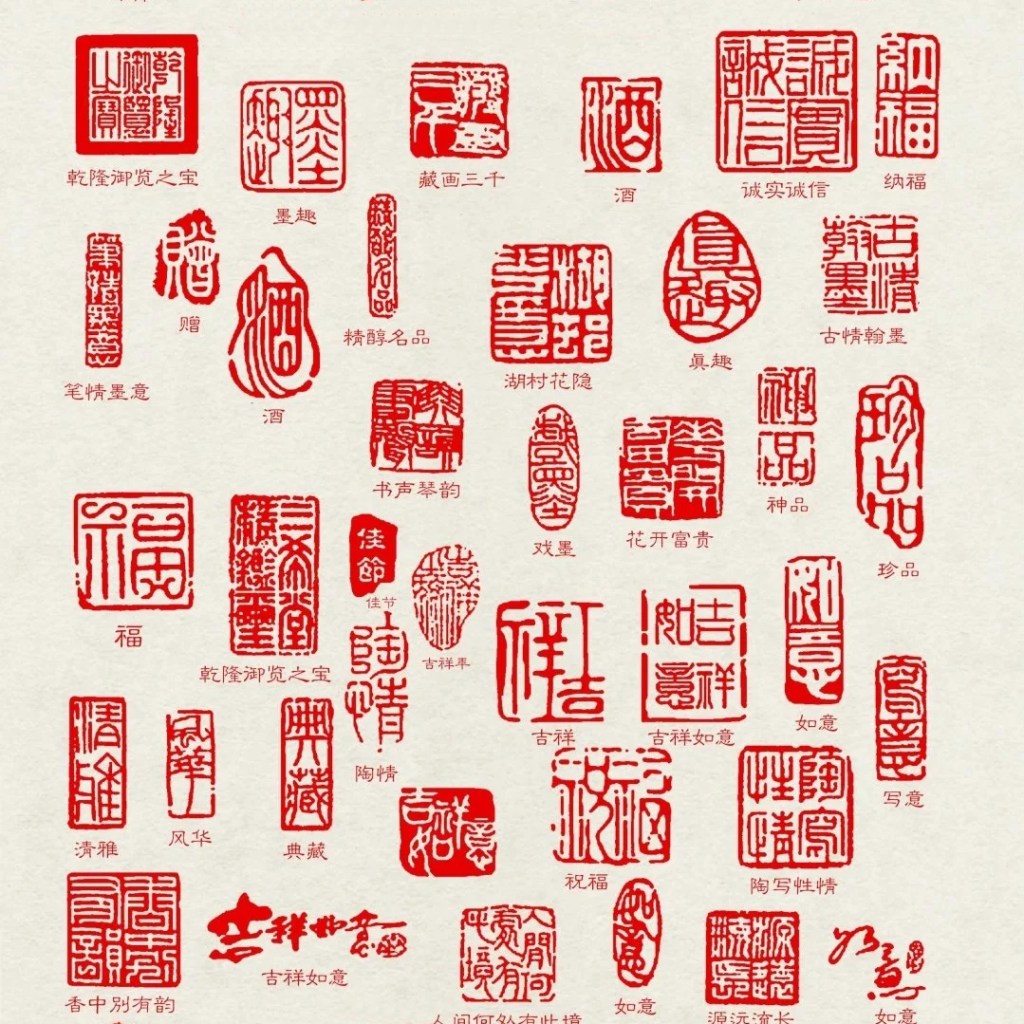

Later, other red pigments carried the same emblematic charge. Hair partitions and bindis on married women’s forehead (traditionally either Sindoor, a mix of turmeric, lime and Cinnabar or Lac coated with Vermillion) tell, for all to see, of their commitment to a man and her spiritual misson as a woman.1 Vermillion, too, chosen as the colour of Life and Eternity, lavishly covered temples and Imperial palaces in China. Red ink was the prerogative of the Emperor, but everyone sealed, and still seals, their precious documents or artworks with Vermillion paste, a gentle blood pact but powerfully symbolic nevertheless.2

Traces of ‘blood’ can also be found in the sexy Sanguine, a colour name used more for pencils than on paint tubes, and in the intriguing Dragon’s Blood—a total myth that one. Not that dragons don’t exist, of course, but this particular shiny and sticky red substance was not collected from a dragon’s belly punctured by an elephant, as the Medieval commercial blurb went at the time but, more prosaically, from the resin of the Dracaena tree. I know. Life is disappointing sometimes, but how could I resist adding it here? Cinnabar of the Indies, its other name, was already quite exotic, but Dragon’s Blood is altogether the best pigment name ever, in my opinion.

A more mundane bloody pigment recipe is to be found in a Medieval Lombard illuminator’s notes: “If you want to make a bit of good red paint, take an ox …” Not sure how many litres of paint that recipe would produce, but it does seem like a slightly overblown shopping list. Nevertheless, oxblood is the only one true to its word; using real blood to dye fabric and leather, it also entered into an artist’s paint composition. That one gave its name to a colour—a dark red with interesting purple undertones usually— still used today but does not refer to a specific pigment anymore.

(Spoiler alert 1: It turns out that blood also played a non-negligible part in the discovery of another colour when animal oil (a distillation of animal blood to which potash is added) was used by mistake in the production of Florentine Lake one day and resulted, instead of the intended red, in a deep, deep blue! More about Prussian blue later…)

(Spoiler alert 2: It seems that not one but two paintings actually used a real heart as pigment. And not just any old hearts mind you but those of the Kings of France Louis XIII and Louis XIV!3)

Onward to the precious one which shines so mesmerisingly and is probably responsible for much more blood being spilt than ever was to make oxblood paint! Being soft, gold is either applied in liquid form or pounded into delicate leaves and then glued directly onto supports. In certain parts of the world, gold leaf flakes were also sometimes sprinkled for a more random effect, while gilders, who also used gold in powder form, made sure to recycle every ounce of their expensive primary ingredient and so invented Shell Gold, a painstaking process which turned these skewings into a gold ‘watercolour.’ If you are patient (homemade recipes exist but are tedious) or rich (you can buy ready-made Shell Gold pans at gilding suppliers) and want genuine gold on your brush, that’s the only paint available as gold is not turned into other ones, even less put in a tube.

Gilding entire backgrounds was just the thing for a while, but at some stage painters began resenting the scattering of light gold produces, claiming all the attention and interfering with a proper reading of the painting. Also, as their skills improved, they understood that a good old yellow astutely applied could much better render gold than… gold! While alchemists were trying to speed up the process—they believed had naturally occurred inside the planet from vile materials, lead being the vilest, to the noblest one, gold—artists had actually understood how to turn lead into gold! What were the best pigments to render gold? Lead Tin Yellow, Lead Antimony and Naples Yellow (also lead-based.)4

That didn’t change their patrons’ point of view much, or their lust for bling and, to give them their money’s worth, halos still shone on brightly for centuries. After these disappeared, gold moved onto the frames.

As a result of this ludicrous lust many homo not-so sapiens seem to share, it probably helped the popularity of yellow paints if their name was somehow evocative of the precious metal and over the centuries, many did. One of the oldest ones, Orpiment, literally means gold pigment, while one of the most recent is Aureolin. Whereas all its family seems content to be called Cobalt Blue, Violet or Green, when it came to christening the yellow, the Middle English aureole, halo, was chosen: a name which came from aureolus the feminine Latin of golden.

Mosaic Gold, a yellow sulphide of tin, was another (poor) substitute to gold used, as we saw, in 13th and 14th manuscripts, while Lombard Gold revived an antique Greek recipe for a yellow made from tortoise bile. Lacking tortoises, presumably, the medieval version used “the gall of a large fish” added a little chalk, some vinegar and Abracadabra… Gold! (Well, a yellow pigment, at least.)

Somehow over the centuries, all these tricks paid off in a way. I remember vividly my mother telling me in a museum once when I was little: “Look closely because everything that shines is gold. There is gold in that frame, gold in that little alcove above the Virgin Mary, and gold on that angel’s wings.” She was correct, but times have changed. Nowadays, we know how to attach colour to mica flakes so that most of what shines… is not gold. Even writing GOLD on a tube of paint containing not an iota of it is not only OK but normal, as an absolute confusion between the colour gold and the metal itself has prepared us to accept this.

After the Earth and its shiny delights, let us now turn our gaze to the heavens and our last intangible colour, no doubt the trickiest of them, for which came first? The l-azul-i of the lapis stone or the azur of the sky, which might have given its name to the stone? After coming across the fascinating fact that in the ten thousand lines of the Indian Vedic poems, the sky is never mentioned as blue; that in the Old Testament in which Heaven and Earth are separated on page one, again it is never blue; and as the Right Honourable William Ewart Gladstone, prime minister of Great Britain for 12 years, had correctly noticed, not once sky or sea are mentioned as blue in the entire Iliad and Odyssey—and there’s a lot of both in the books! —I began to suspect that perhaps it was lapis lazuli, aka the stone, which had given its name to the sky… however odd that was! As soon as that doubt entered my mind, I easily found out that, indeed, the word lazuli comes from the Persian لاژورد lazhward which is the name of a place, a place famous for a very special deep blue stone veined with gold, the beautiful lapis of Lazhward. And so the blue egg came first!

Later, and may Jupiter, god of the heavens, be thanked perhaps as the Romans finally were able to perceive the colour blue that not only Homer but all the Greeks previously couldn’t, being, as was suggested by the same Gladstone, all and every one of them poor souls… colour blind!5 There’s, of course, a more reasonable reason for the presumed ‘absence’ of blue in ancient Greek. In fact, three adjectives exist and could correctly be translated as blue, depending on context. But colour terms in different languages don’t align, not even today, as we’ve seen. English is not Ancient Greek, in which colour terms often were used as metaphors, poetic tropes reflecting a colour experience, or even a physical phenomenon rather than any defined hue.6 In Gladstone’s time, “scientific” colour wheels had appeared (even if indigo was still there, reflecting no science but Newton’s arbitrary decision), but the man did not perceive that the English colour terms were simply one way of seeing the world, a rather parochial way at that. And, much is the pity when you need to colourblind an entire people to prove your academic point… Better off trusting the poets, really:

La terre est bleue comme une orange

Jamais une erreur les mots ne mentent pas (Paul Eluard)

Earth is blue as an orange

Never a mistake, words do not lie

The stunning sky-blue sacrarium recently discovered in Insula 10 of Pompeii’s Regio IX. Photo © Archaeological Park of Pompeii

The Romans, being as always more practically minded, decided they did need a word for the hue and that Caeruleus, derived from caelum meaning both the sky and the Heavens, would be just perfect a generic word to describe the colour of all blues7, including their synthetic one (whether the blue frit in question came from Egypt, Scythe, Cyprus or later from Pozzuoli, in Italy.)

Over the ages, men forgot how to make this celestial blue. But the name was revived from the old Latin one in the 19th century in honour of a new pigment developed, a cobalt tin oxide compound. That most heavenly Cerulean Blue is still found on our tubes today.

Jump to the next section of the book by clicking here

Alternatively click on the Table of Contents to browse the sections.

You can also subscribe to my blog at the bottom of this page,

and you’ll receive Hues in Tubes in your inbox… as it gets published!

Additional information and references

- “When a married woman draws a line with Sindoor, it touches a spot called ‘Brahmarandhra’. This spot is of immense spiritual significance. When a child is born, there is a tender spot on the middle of the head (where there are no bones found – after a few years, this spot gets covered with bones). This tender spot is called Brahmarandhara. It is through this passage/spot that a soul enters one’s body. When one wears the Sindoor on the hair partition, it is a representation of the power of women – who can create life on earth.” https://theverandahclub.com/article/indian-married-woman-and-the-meaning-behind-their-symbolic-accessories-654 ↩︎

- “Wax seals as we know them today first gained prominence during the Middle Ages in Europe. As literacy increased and written correspondence flourished, wax seals became essential for securing letters and ensuring their privacy. Initially, simple knots or ribbons were used, but soon they were replaced by wax impressions bearing distinctive designs. At this time, sealing wax was commonly crafted by combining beeswax with Venice turpentine, an extract from the European Larch tree. Initially, the wax used for seals was in its natural, uncolored state, and would be stamped with a signet ring. However, as time went on, a vibrant red hue was achieved by incorporating vermilion pigment into the wax mixture. This addition of color added a visually striking element to the seals, making them even more captivating and distinctive.” Cody’s Blog, The History of Wax Seals, 2013. [Online]. [Accessed 2 March 2025]. Available at: https://codycalligraphy.com/blog/wax-seals-history/ ↩︎

- https://www.unjourdeplusaparis.com/en/paris-insolite/coeurs-famille-royale-tableau-drolling-louvre ↩︎

- I got this fun fact from listening to a talk about The Book of Colours (Das Farenbuch) with Dr Juraj Lipscher. ↩︎

- I have another theory about the absence of the colour blue in Homeric texts, however. It developed after ten days immersed in the sea and sky of little Greek islands and discovering there that, despite their lives simply infused on all levels with gods, goddesses, and, seemingly, their entire time spent dragging tonnes of white marble up the highest hill around to worship them, the Greeks had, apparently, no word for religion. There you go. When something is as obvious as blue, occupying the top half of your horizon in Cobalt blue and the bottom half in Ultramarine, there is no need for a word, the world is simply blue. That’s your blank canvas—on which, it will be admitted, your white marble does pop… so there’s a word for that! ↩︎

- Deutscher, G. (2011) Through the Language Glass, Why the World Looks Different in Other Languages. Picador, New York, NY, USA and An Australian Colour Society’s talk “Making sense of Ancient Greek Names” by Dr Peter Gainsford has totally dispelled any doubts I could still have about that controversy, but I could not find an article to share here, except this one, not from Dr Gainsford, however. Yglesias, M. The bizarre myth that Ancient Greeks couldn’t see blue (2022) [Online]. [Accessed 2 March 2025]. Available at: https://www.slowboring.com/p/greeks-blue ↩︎

- Even back then, the link between the colour blue and spirituality was strong as a recent finding, a stunning sky-blue sacrarium (a space for ritual and conservation of sacred objects), has just been excavated in Pompeii. Brilliant red lines the niches, where statues and other devotional iconography likely stood. [Online]. [Accessed 2 March 2025]. Available at: https://www.thisiscolossal.com/2024/06/pompeii-blue-frescoes/ ↩︎

Discover more from in bed with mona lisa

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

One Comment Add yours