I thought it might be interesting to be able to scroll down the chronology of these 88 pigments… and have added a little story about each, just because…

(Although most of that information is available elsewhere in the book, it is scattered and might be easier to access thus.)

Japanese Pearl White is made from oyster shells. The shells are collected in large heaps by the sea-side in Kyoto, where they rot quickly in the warm and humid climate. Over a decade, the organic

compounds decompose, leaving behind the finest pearl white flakes. Ground further, sorted by size, Gofun was the most important white in Japanese art and crafts. Mixed with a rabbit skin solution and applied on a sized ground, it can then be burnished to a gloss with an

agate burnisher. There is only one Japanese manufacturer still producing genuine Gofun Shirayuki.

Gamboge, made from the crystallised resin of Garcinia Gummy-Gutta, a sort of latex tree, takes it name from where it grew: Camboja — the antique name of Cambodia. The solidified pigment was sold in the bamboo canes in which it was collected from the trees and often called pipe gamboge as a result. Being a resin, it is a non crystalline, amorphous material with poor lightfastness and probably best remembered as the partner pigment to Prussian Blue in Hooker’s famous green. The man, Royal Horticultural Society’s botanical illustrator, was weary of mixing these two colours all day long and asked his pigment dealer to premix them to save him some time. These days it’s still available, as indeed it is most useful, but as a hue.

It wasn’t until we finally understood the unusual process needed to turn lazurite into a celestial blue that illustrators chose to lavish it in their Bibles. Until recently, it was thought lapis arrived later in Europe yet the most amazing find — the skeleton of an aged woman in the cemetery of what had obviously been a flourishing nunnery in Germany— forced us recently to revise our datation somewhat. The lady died around 1000-1200AD but left behind the most unusual evidence of what her contemplative life had been all about. Embedded in the dental plaque of her teeth, more than a hundred tiny flecks of blue pigment told the tale of a paintbrush repeatedly humected and shaped back into the fine point needed for the detailing work and embellishments of manuscripts… a labour of love no doubt!

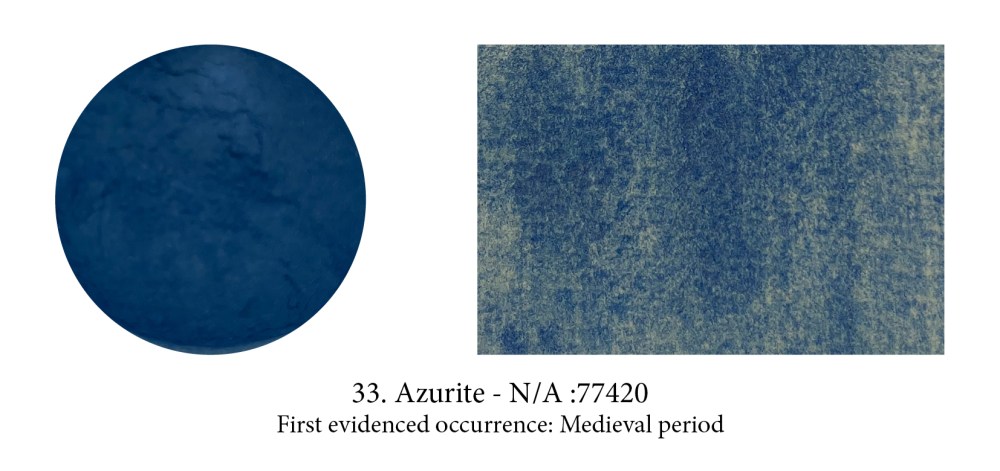

Although naturally and often found with Malachite, Azurite had quite a different destiny. Evidence in graves (and possibly as an exciting eye shadow) has been found at the Neolithic, Central Anatolian site of Çatalhöyük, then attributions in Ancient Egyptian painting are few and disputed but its time was coming… Often used in frescoes and manuscripts in the Middle Ages, then as underpainting or in combination with the dearer Lapis in oils, its multiple hues made it the most important blue pigment in European paintings from the XV to the XVIII century.

Used less frequently than gold in illuminated manuscripts, silver was favoured for the depiction of armour. Saffron glair was often added to silver paint so its not hard to guess which, of gold or silver, was the most valuable of the two then and there (it was not the case in China actually) but the main difference between them is that silver tarnishes when in contact with sulphide-containing pigments, and often now appears black. This was put to good use in silverpoint drawing implements where the extremely fine silver wire would, on prepared grounds, turn black and leave the finest of lines.

PS: Its Latin name argentum also gave a country its name… can you guess which?

Are you dying to know why lakes are called lakes? Hear the tale of Lac then… Used as a dye as early as c.1500 B.C.E., Lac (or Lack) was later turned into a vibrant, transparent, deep red-violet pigment known as Indian Red. Co-created with the host tree, it was not understood for a long time that it resulted from a sting from a female scale insect and the reaction from the tree. Its name actually comes from the sanskrit word for one hundred thousand… that’s how many were thought to be in a single scarlet resinous secretion! When the same insect was actually left to hatch and fly away, only the resin remained on the branch, a blond substance that was turned into a lacquer, known as shellac. Infinitely cheaper than Vermillion, Lac took the art world by storm. Eventually, its popularity extended its name to all the other insect-based red colours then to all pigments produced from a dye.

Meet the intriguing Dragon’s Blood — a total myth that one. Not that dragons don’t exist of course but this particular shiny and sticky red substance was not collected from a dragon’s belly punctured by an elephant, as Pliny’s commercial blurb went at the time but, more prosaically, from the resin of the Dracaena tree. I know, life is disappointing sometimes, but tell me how could I resist adding it

here? “Cinnabar of the Indies”, its other name, was already quite exotic but “Dragon’s Blood” is altogether the best paint name ever in my opinion.

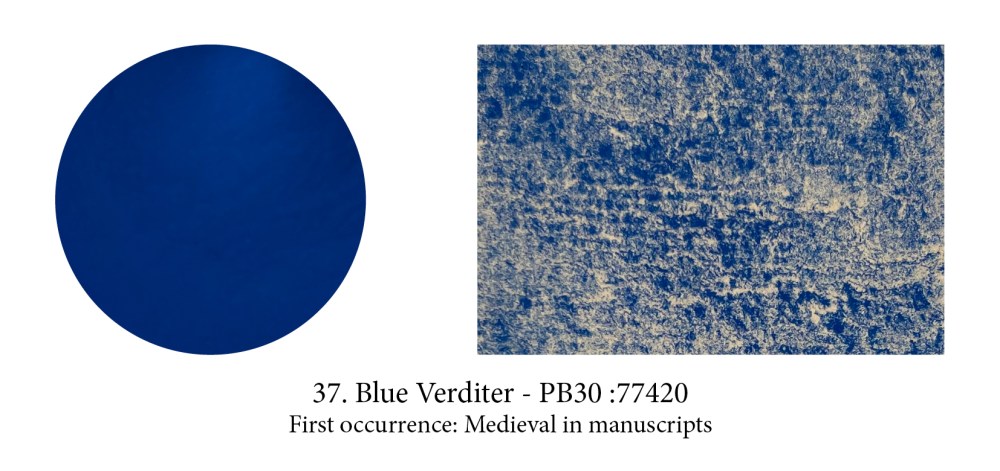

Blue Verditer, also known as Blue bice or ashes, is chemically and structurally analogous to Azurite, a ‘basic copper carbonate’. Produced since the early Medieval period to substitute for more expensive blues, and Azurite itself of course, it had none of the qualities required for a pigment (Fugitive, incompatible with many other colors including Lead White and Vermilion) except perhaps its price which explains why it was still in use in the 19th century but to paint wood panels in homes rather than on any easel painting.

It has been used by the Mesopotamians, the Indians, the Japanese, the Egyptians, the Greeks, the Romans and the Aztecs to caulk boats, waterproof baths and tunnels, consolidate fortifications, cast statuettes, set jewellery, create pavements and as paint too of course or I wouldn’t mention it. In 312B.C.E., the Seleucids and Nabateans fought hard for the place where it occurred naturally. The first oil war not quite, although… Have you guessed what it is? I’ll give you a hint. It was used to soak the shrouds wrapped around bodies, and eventually gave its Persian name, mumiya, to the

embalmed corpses themselves. This elusive dark brown glazing friend, annoyingly sticky and beautifully transparent, is known as Bitumen (or Asphalt.) Tar sands are natural occurrences of bitumen, and that name actually sums up its two components: the organic crude oil and non-organic sand.

Eggs seem to play a large part in art materials world… as a binder! There are many variations on the tempera emulsion recipe sometimes using the whole egg, only the white, only the yolk, sometimes some oil is added, and sometimes it’s even emulsified in beeswax. Also, there have been many a criterion found for choosing these eggs over those eggs — with colour of the shell to provenance of the chook (or whether from country or town) giving many a fascinating discussion as you can imagine! — but freshness seems to really be the number one. (However, tempera would rot after a few days… Hum!) However, if your egg is white, don’t throw away the shell as, crushed, it can make a pigment producing “an incomparable white which cannot be surpassed by Lead White” assures us the Secreti di Don Alessio Piemontese, a well-known ‘book of secrets’ that was first published in 1557.

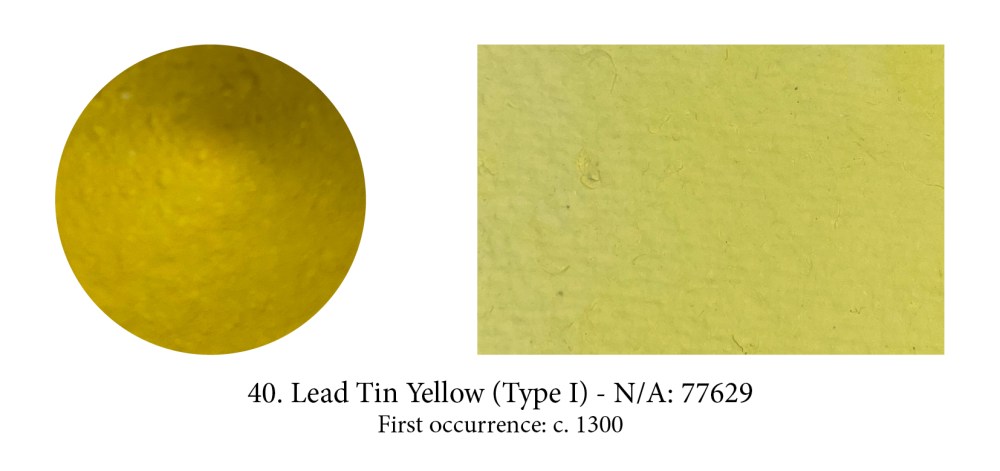

Lead-Tin Yellow type II is, in fact, the earlier pigment (I know, I know but I’ve had nothing to do with this classification and agree it’s just annoying!) Traces of type II lead tin oxides are attested in Roman mosaics, yet as a paint pigment no occurrence of either type have been found before Giotto’s Last Supper, c 1300. After that, a number of paintings use type II, yet type I seems overall to have artists’ ‘preference. What’s the differences between them? Their particle shapes!! We knew they resulted from quite different methods and were slightly different in colour but, even with a microscope you would find nothing else to tell apart the fine particles yet with the higher magnification of an electron microscope, quite different particle shapes are visible… no wonder it took so long to tell them apart!

Today Stil de Grain genuine doesn’t exist on our palettes anymore, yet lingers in a few ranges as a colour name. And Sap Green, its partner pigment, has nothing in common with the original one. Both were produced from buckthorn berries — ripe/unripe would modify the colour. Along the way, I found out that the buckthorn berry was called in French graine d’Avignon, Avignon seed, so graine to Grain seemed a plausible step. Still, if it definitely sounds French, Stil de Grain really means nothing in French. So I did one more check and omg, according to the most respectable Dictionnaire de l’Académie Francaise, Stil de Grain actually derives from the Dutch colour schijtgroen, literally shit green!

Indian Yellow smells. A not unpleasant cow shed sort of smell actually… At the time suggestions were made: a particularly smelly plant? camel urine? castoreum, an anal secretion beavers use to mark their territories? An odd one for sure. Finally, curiosity took over, and the director of Kew Gardens sent Sir Mukharji, an Indian expert in art materials, to check out its production in the

village of Mirzapur, where it supposedly came from. He came back with this tale. (No evidence of this strange pigment production survives however… so you chose to believe it or not!) Indian yellow was the result of feeding nothing but mango leaves to some poor cows, he reported, then heating their dark yellow urine to reduce the liquid and turning the dregs obtained into orange-sized balls left to dry in the sun. (Once dry they are no more than lemon-size… or at least the ones I saw/found in the Cornelissen archive.)