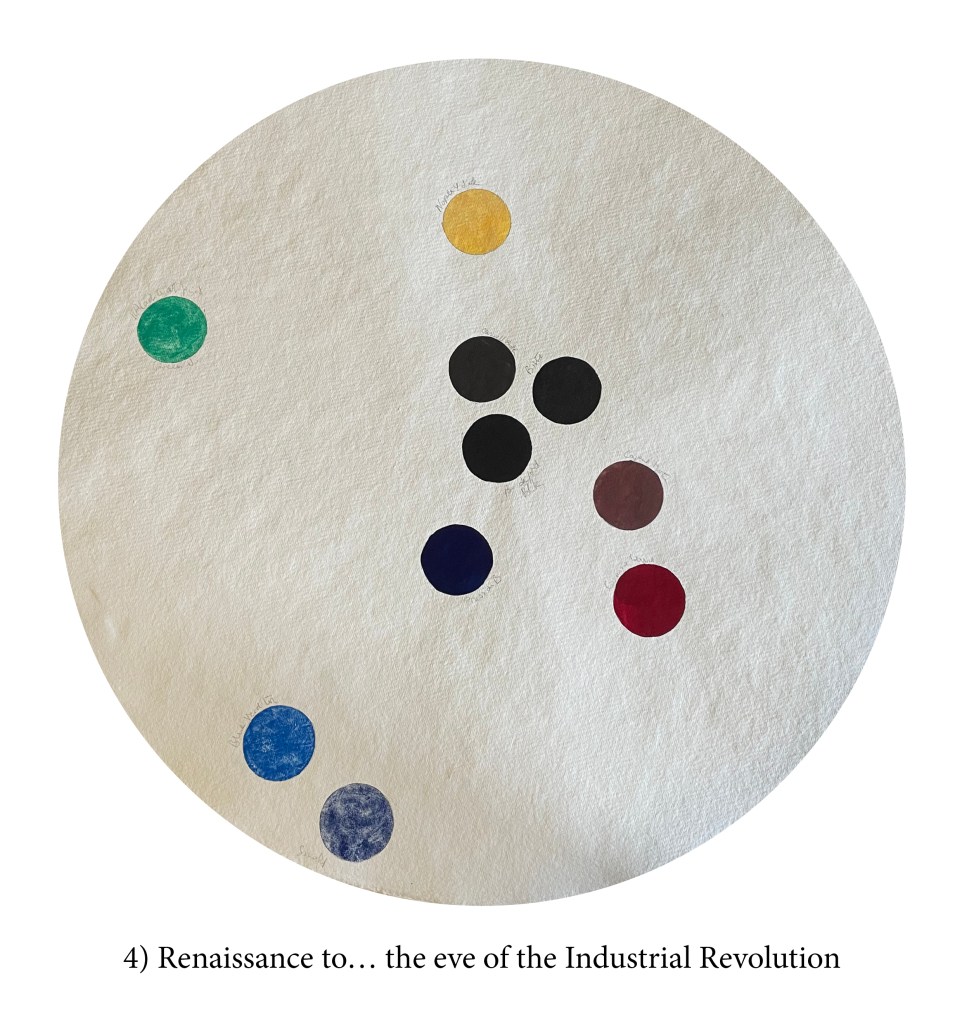

I thought it might be interesting to be able to scroll down the chronology of these 88 pigments… and have added a little story about each, just because…

(Although most of that information is available elsewhere in the book, it is scattered and might be easier to access thus.)

Mesoamericans, of course, hadn’t waited for the Conquistadores to show up to discover for themselves that the female of the coccus cacti, a scale insect, produced an incredibly vivid red which could be used both as dye or ink and, when they arrived, production of it was in full swing in Mexico’s southern highlands where the prickly pear cactus thrives. The Spaniards were quick to

demand that taxes be paid in that ‘red blood’ and it took some seventy thousand insects to make a pound of dye — despite 20% of cochineal’s body mass being dye! By the time it reached the shores of the Old World, however, the cochineal louse turned into a seed for centuries under the name of grana. A fact some questioned, yet it apparently took the invention of the microscope, enabling the curious to see the little legs of the beastie, to settle that controversy!

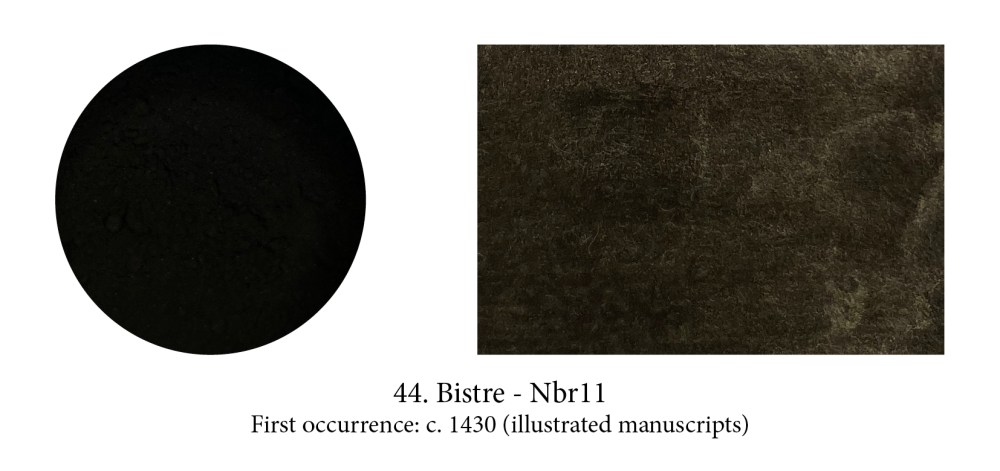

Bistre is to the browns what Lamp Black is to the blacks… but not as famous! Made of beech soot mixed with distilled water then cooked down to thicken, the resin then separates from the mixture and, a few washes later, gives you a beautiful ink with hues from pale brown to dark, even near black. It was used often for washes in drawings and easily confused with Sepia, yet this pigment was also used in oils, even watercolours.

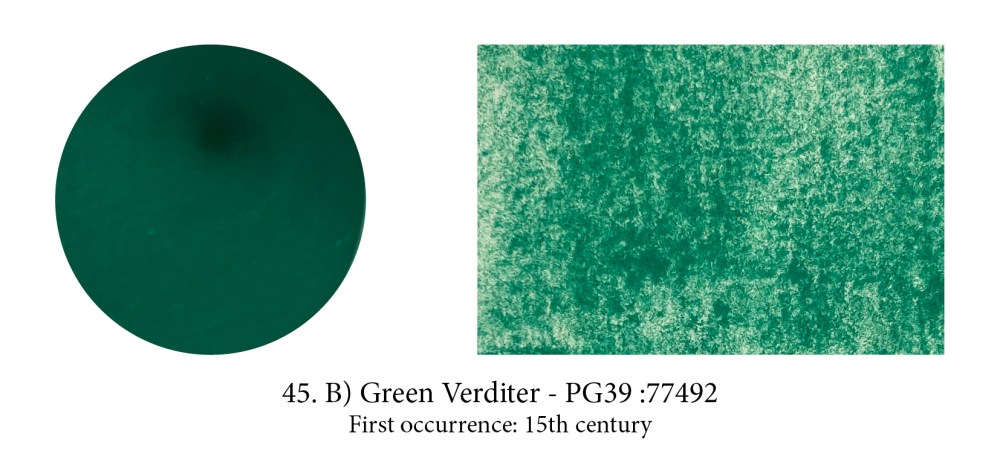

A paler colour than natural malachite, Green Verditer, its synthetic counterpart, is also a copper carbonate hydroxide with a crystal structure identical to malachite. When synthetic Azurite often went by the name of Blue bice, Green Verditer was also known under the name of Green bice. Despite the fact there were so few green pigments (and so much green out there!) usage of it in paintings was never as frequent as the blue, although detected in Russian Orthodox frescoes.

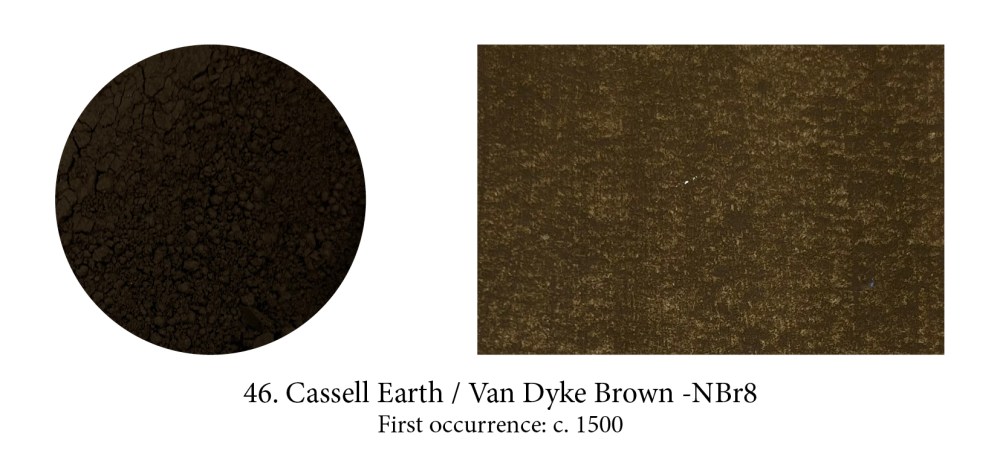

This humic Earth, typically associated with the so-called Van Dyke brown, is described as ‘an earth containing bitumen’. However, to quote Terry (1893) “What the original brown used so much by the great van Dyke [sic] was no one can tell.” Today you hardly ever find Cassell Earth in tubes but every range will have a Van Dyke brown and they will all… be different! (In composition and in hue.) Interpretations by paint makers of what that colour was…

Smalt is gritty and so should a glassy pigment be. Unlike Egyptian blue, another glass pigment which contains copper, this one gets its blue from cobalt. It is quite strange how important this very transparent pigment was from the 15th century to the 18th, especially as it handled badly in oils (but it was very cheap to produce and blues were dear!) This being said, the colour is somewhat unusual and quite pleasant I find.

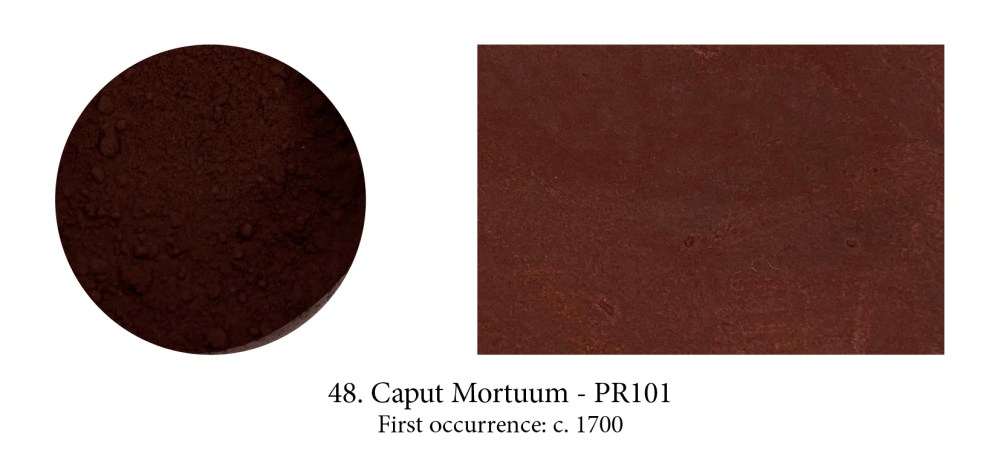

Caput Mortuum’s name was, and is still often, used for Mummy Brown, but that’s a misnomer. This soft mauve-brown synthetic pigment saw the light of day as a byproduct of sulphuric acid manufacturing during the 17th century and is still found in many ranges. Its Latin name is a lure, borrowed from alchemy in which it signifies a useless substance left over from a chemical operation such as sublimation or oxidisation. Alchemists represented this epitome of decay with a stylised human skull, literally a “dead head.” So sorry to disappoint but Caput Mortuum, never made from

crushed skulls, is a banal synthetic iron oxide with a fancy name…

Yes, it was discovered in Berlin, then the capital of Prussia, and so did go under both Berlin and Prussian Blue for a while —geographically correct both of them— and it was the first ‘modern’

synthetic mineral pigment, created entirely in a lab (and entirely by accident too it must be said.) At 10% the price of Lapis, but 10 times its colouring power, this pigment took the art world by storm… The Dutch brought it to Japan in 1763, where it became known as “the blue imported from China”and by 1830 the prices had dropped so much it was used as a block printing ink. In fact out of 8 colours in the 36 views of Mount Fuji by Hokusai, 4 were for shades of Prussian blue.

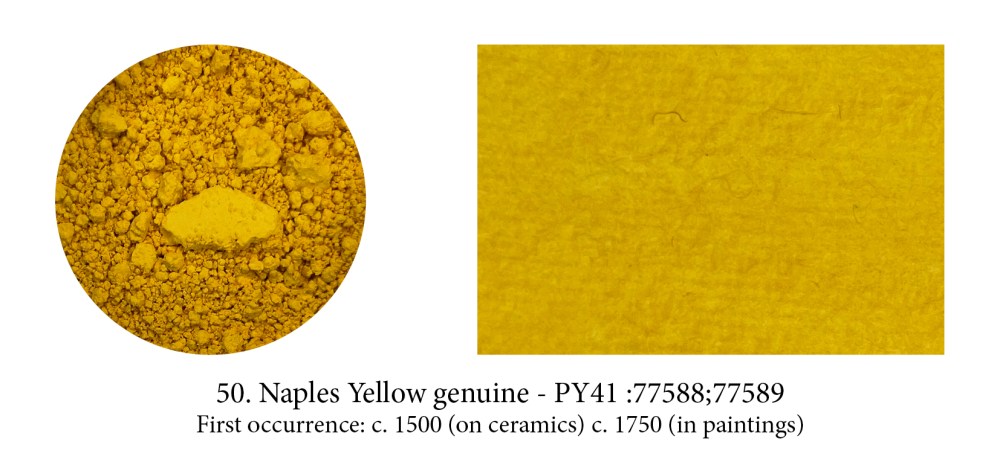

Legend has it, ingredients came from the flanks of the nearby Vesuvio volcano yet none exist there. Also, Naples Yellow must be the most undefined colour, then and now. Today it’s because it’s not made, as it used to be, by heating lead and antimony, so it’s always a ‘hue’, a mix of safer pigments. Then, it was because that process allowed variations from lemon yellow to virtually orange. The best of unstable yellows at the time, painters loved it… as to why it’s called that? No-one knows!