WHAT?

I. What is paint?

Paint is a concept, but surely you were all aware of that.

In a hardware store, you might ask for paint for this or that. You are simply trying to find the best one for the support you have in mind to colour. In an art store, there might be some restrictions as to which surface would do the job best with your paint, but usually, the choice of paint is all about what’s pleasant or suitable to your practice. In extreme cases, however, the binder might restrict your options. If you wanted to paint underwater, as Else Winkler von Röder Bostelmann fascinated with the sea world indeed did, forget about watercolours, gouache or any other water-soluble paint, obviously, but oils will do the trick quite nicely, thank you!

You are free; you choose and choice… there is! Under the paint header, and in more or less chronological order, you will find ink, distemper, encaustic, casein, gouache, tempera, oil, printmaking ink (which is nothing like ink, more a dense oil paint), watercolour and polymer dispersions such as acrylic and vinyl—not to mention, as I’m not 100% convinced, yet, they deserve to be included in this noble list, the new hybrid ones: water-mixable oils, Aquazol-based ‘watercolours’ and acrylic ‘gouaches’. If you are already lost—and it’s a certified fact that many do get lost in art stores—it’s because the paint ‘concept’ presents itself in such a range of material realities.

After keeping company with all of these for some years, I now see the different options more like a series of classrooms: the lab, the gym, the science room, the drama room, the library, etc. In short, different places in which you go about things in different ways but in which you learn and are at school; that’s the unifying concept. In the case of paint, the unifying ingredient is the colouring agent, usually a pigment, but the discipline, which will turn it into different substances, is the binder. The resulting material not only achieving different results but asking of you quite different skills too. Still, if all of the above is paint in the end (ink could be debated although excluding it would exclude the near totality of Asian art, and you also apply it with a brush unto an absorbent surface like you would watercolour so I’ve chosen to include it here) and yes you can paint with them all, it does not even begin to take into account at all—and we must—the character of the kids in the room. Some will be happy in drama and yawning in science; some will be late and lazy, others too eager: it’s them pigments in the paint I’m referring to. All those which we shall tackle in this book go to the Pigment School of Art and are a handful of wonderfully temperamental and singular characters that seem to have only one thing in common: to be suitable in artists’ paint… which perhaps gives them a particular affinity with the temperamental and singular characters that will use them! As teachers have understood, painters have no choice but to get to love, perhaps not, but at the very least, know their colours well. That’s the way to achievement in the classroom as in the studio, and, in truth, it is also worth their while as each and every one of them true individuals can take you to such beautiful colour spaces and has a fascinating story to tell.

In a school, the music teacher might be searching for something quite specific, maybe a good voice, while the sports teacher will be interested in how fast she can run. The drama one in how confidently his body moves, the philosophy teacher might encourage his enquiries, the literature one her imagination, the maths one his abstract reasoning. Meanwhile, in our Pigment School of Art, an art historian might be researching a pigment to determine a datation, a conservator double-checking that the pigment in question was available to artists at the time to ensure the authenticity of an artwork, a restorer seeking to match a now unavailable pigment and a paintmaker whether it should be added to his range. Whilst you, the painter musing in front of the ranges, might wonder whether you might want to paint with it all!

Others, outside of the Art school, will look upon the same child in quite different ways. A grandmother (geologist) might wonder whom in the family he got his freckles from (deep time’s conditions that brought about this specific rock formation). A mother (chemist) might be looking into a new school for him (crystalline formation to determine whether a variation in its particle shape might bring on a new property). A distant relative (traditional owner) might ponder belonging, wonder what relation to country and significance to the elders this little one has. While his best friend (pigment forager) can’t wait to play with him… I know these other pigment lovers exist. I enjoy their stories and try my best to navigate their jargon and stories because I share the fascination. Still, I cannot see what they see. Same material…. Such different narratives!

My interest in pigments was ignited by the necessity to understand the qualities and characteristics of the various paints artists use. Because I worked in an art store and needed to answer my clients’ questions and because, well, quite simply, because I’ve come to love Art. Still, I cannot agree with David Coles, who writes in Chromatopia, that

“Pigments have no intrinsic value. It is not until they go through the transformative process of becoming colour [he means paint, here] and, in turn, art that their potential becomes realised.”2

I do understand that for him, a paintmaker, the raw material might be only that, a raw material waiting to be turned into his beautiful paints and later into artworks and, of course, this book is about paint, but the complex and fascinating nature of pigments has now long overtaken my initial interest in them as merely the colouring material in all art supplies. I indeed met pigments caught in the oils and resins of old Masters’ paintings long before I even had a clue about them in tubes as paint… and even less as the free agents all of you on the Wild Pigment road might know them as. Still, I now feel close to those of you who fossick, grind, sieve and share your astonishments, admiration, and love. My curiosity about pigments seems endless, and encountering an array of like-minded Pigment People recently (all true individuals, however!) has given me incredible joy and a profound sense of belonging. Belonging to this planet and a community of passionate ones, all seemingly leading good lives, sharing my concern for kind ways of treating and extracting pigment and expressing it in one creative way or another. (And I’m not alone! Being on the board of Pigments Revealed International3, the first not-for-profit pigment organisation, I can vouch for many more Pigment fans out there without the slightest interest in turning these into paint.) Plus, some artists—the most famous one being Anish Kapoor, I presume—have used raw pigments in their artworks.4 Due to the volatility of the material, it’s not easy to do, and often these are ephemeral art installations. Still, it can be done. Other artists, who do paint with those they gather, treat them as friends, even counsellors and seem to develop a very special and personal relationship with them. Hear what artist Hana Shahnavaz, who collects some of her pigments on the island of Hormuz (Iran), says about them:

“I find that older pigments, which come from a settled place, bring about a sense of stillness and calm, whilst modern pigments, introduce a sense of wild freshness that the eye is not accustomed to. To create work that weaves these two harmoniously is my current labour of love.”5

While Catalina Christensen, who works with pigments from her native Columbia, always gives them a place of honour in her displays:

“The starting point of my work is the creation of the pigments which are as important as the paintings and which are exhibited along my works.”6

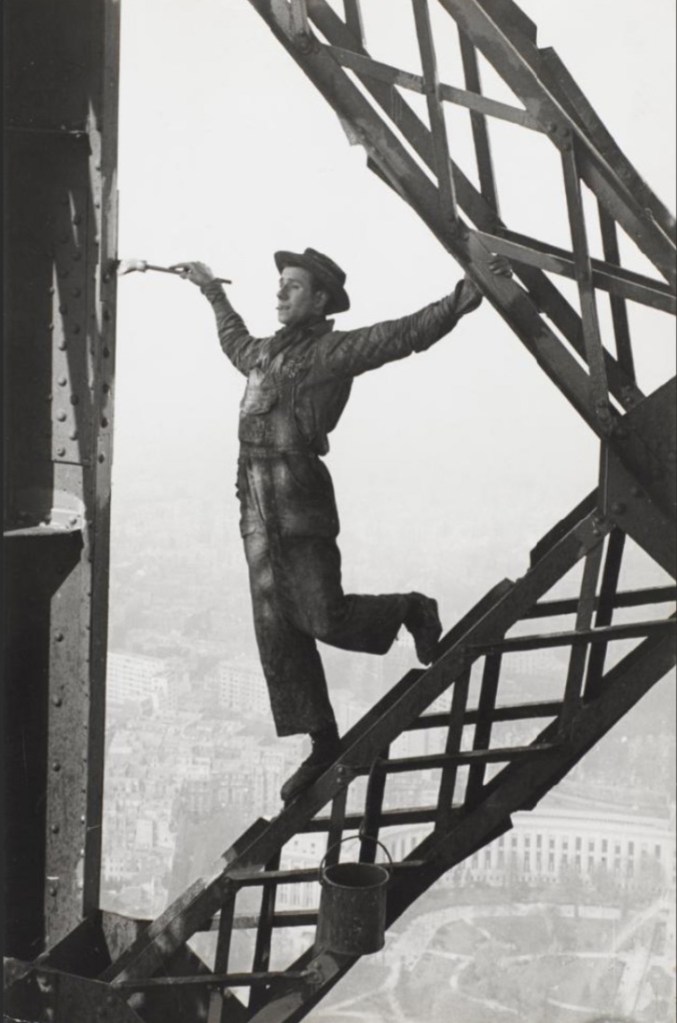

House paint is a different paint, made to meet other requirements than paint for artists (opacity, super quick-drying time, uniformity, etc.) I have no contempt for paint in buckets at the hardware store, but again, have no real understanding of it either. I once had the pleasure of sharing a meal with a lady who devises paints for very unusual surfaces. At the time, she was working on a paint for the Golden Gate Bridge, a more durable one that would save money further down the track, as it would better survive extreme sun, daily fog, salted air and the pounding of soft and seawater waves. Her other project was to find a paint suitable for the iron beams and a dye for the carpet of a client’s corporate foyer, both matching perfectly the colour of their logo. I was totally fascinated, yet talk of understanding the chemistry that would go into these paints and dyes, an entirely different world! Let’s just say for now that binders suitable for one job are mostly unsuitable for the other. Also, most art pigments are far too dear to paint your bedroom with, let alone an entire bridge… However, for centuries, artists have painted on precisely that: buildings. The walls of palaces, tombs, pyramids, churches, and wealthy patrons’ villas were covered with the same pigments we would, even today, paint our houses with. Yet, precious ones were used too, but then the client was often, quite literally, King!

Painting a house is also a different job and requires another set of skills than those needed to paint an artwork. One of the things a house painter doesn’t need to know about is what his paint is made of. Today, the base pigment is usually Titanium White. After that, some colourant(s) are added to turn it into a mysterious sounding and alluring colour, but as to its composition? Who knows, and, in truth, who cares? It does the job, and another coat will cover that one before too long.

But I firmly believe (I wouldn’t be writing this book if not) that there is an art and a craft to a painter’s work and that artists should know about their paints. Not for paint’s sake but because there’s a satisfaction to be found there. In fact, understanding all their materials would be a good thing because, as Rauschenberg aptly puts it:

“You begin with the possibilities of the material.”7

And, may I add, you also end there, as no more than infinite growth is possible on a finite planet, can you expect your material to do what it cannot. For all the rest… do as you will, most certainly. “Disregard the rules,” even, as Ian Gentle suggests, “ but always respect your materials”,8 that’s my motto! Truth to materials and their demands is also adherence to and coherence with the Real. Using materials is akin to abusing them if you do not get to know them intimately and listen to their side of the story. Superficial or strictly intellectual knowledge is not an option either. It would be best to go hands-on and get yourself dirty, or you might risk missing this whole other, subtle, yet perhaps more valid, dimension.

Among the excellent and other rewarding reasons to make an effort? Choosing your paint and colour-mixing becomes easier when you understand the pigments available to you. Producing durable works becomes a piece of cake (whatever crazy combos you want to invent) and will save you crossing the street whenever you meet one of your patrons! Technical options will open up new avenues and give you more freedom in your work. Also, you might fall in love with the information. Is it not fascinating to understand that you are perhaps manipulating clays, volcanic rocks, bones, piano keys and thermometers, seeds, barks, saps of exotic trees, or some fish-turned glue… all in a day’s work? It sure puts you in touch with something tangible and alive, doesn’t it?

Finally, in the words of Johannes Itten, it could be that

“Only those who love colour are admitted to its beauty and immanent presence. It affords utility to all, but unveils its deeper mysteries only to its devotees.”9

I’ll rest my case for now, but hope I’ve convinced you to, at the very least, continue reading!

Jump to the next section of the book by clicking here

Alternatively click on the Table of Contents to browse the sections.

You can also subscribe to my blog at the bottom of this page,

and you’ll receive Hues in Tubes in your inbox… as it gets published!

Additional information & references

- In 1929, Bostelmann contacted the New York Zoological Society and was hired to be the expedition artist for William Beebe in Bermuda. She rendered over 300 plates of deep-sea and shore fish, and her marine life art was published in several National Geographic Magazines in the 1930s, 1940s and beyond—with her depiction of the giant squid (Kraken) and bioluminescence of unknown ocean life causing quite a stir in the oceanographic world at the time. ↩︎

- Coles, D. (2018) Chromatopia, p187. Port Melbourne, Thames & Hudson Australia ↩︎

- Check out the good work that organisation does, and join us for talks and more: https://www.pigmentsrevealed.com/ ↩︎

- Beware, however, as Kapoor has many tricks to make us think we are looking at pigments, mountains of pigments sometimes when a few are merely sprinkled onto a supporting material! Available at: http://anishkapoor.com/716/manchester-art-gallery-2011 ↩︎

- Shahnavaz, H. 2021. Methods and Materials. [Online]. [Accessed 2 March 2021]. Available at: https://www.hanashahnavaz.com/methods-and-materials/ ↩︎

- Christensen, C. (2018) A fascination with pigments: An Interview with CGLAS alumna Catalina Christensen. [Online]. [Accessed 2 March 2021]. Available at: https://material-matters.cityandguildsartschool.ac.uk/pigment/catalina-christensen/) ↩︎

- The origin of this oft quoted line from Robert Rauschenberg seems pretty elusive! ↩︎

- ed. Roach, D. (2023) Ian Gentle, the found line. Clifton, NSW, Australia, The Clifton School of Arts ↩︎

- Itten, J. (1961). Kunst der Farbe, Reinhold Pub. Corp ↩︎

Discover more from in bed with mona lisa

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Sabine these are such unique, stunning photos. Each one is a gem. Thanks you for sharing your extraordsinary book with us.

Excited and curious when your email arrives in the inbox.

Thank you, Edith F

Hello lovely Edith… I do enjoy looking for illustrations for these posts and hope to keep surprising you! Love Sabine