WHEN?

Pigments in History

“Colors are not possessions; they are the intimate revelations of an energy field… They are light waves with mathematically precise lengths, and they are deep, resonant mysteries with boundless subjectivity.”1

Isn’t Ellen Meloy’s definition of Colour in her Anthropology of Turquoise simply delicious? Still, we might as well admit it right now, and despite colours not being something we can genuinely possess, we have tried our mightiest and hardest to appropriate them.2 To turn them into something tangible, something we could hold in our hands, a material substance we could do something with. Colour not only surrounds us, of course, but we embody it too. Despite this overwhelming presence and the fact that we can steal a bird of few of its feathers, a bush a few of its flowers to adorn ourselves with, on the whole, it is an elusive affair. Maddeningly so. In its light form, while Colour parades on surfaces, dictates the rhythm of our days or offers us the rare magical rainbow, we can only admire and not possess. Yet humans relentlessly seemed called to capture Beauty and add it to their treasure pile. To compete with the Creator’s infinite palette, I imagine a command of colour then became a must.

The oddest thing is that not only have we always wanted to appropriate Colour (despite all the horrors soon to be described, the attraction is easily understood), we have also always tried to alter colour. As early as the later Pleistocene, we understood how to turn Yellow into Red Ochre, and from then on, we never stopped. From Mesopotamian ceramicists playing with fire to obtain gorgeous new glazes to alchemists endlessly grinding the black stone the marriage of mercury and sulphur had produced in order to reveal its hidden fiery red, to water spouters changing the colour contained in their vessels by spitting into them, impressing kings and fair-goers alike, we collectively seem to have been virtually obsessed with obtaining the magical powers which would demonstrate not only our understanding of some of the complexities of the natural world but our human power over what is so evidently more powerful than us. And, of course, as any painter mixing his paints could tell you, seeing an entirely new, sometimes surprising colour appear from the blending of well-known ones is mesmerising. In the Qur’an, God is described as a musawwir, meaning both maker and painter, a synonym which led Rumi to poetically comment that God has a “colour-mixing soul”, thanks to which the entire creation was painted! Can some of us feel the stirrings of their colour-mixing soul more urgently than other mortals and become painters? You tell me…

Maybe I’m exaggerating, and perhaps humans haven’t always wanted to appropriate colour. Maybe there was a time when we lived in such harmony with our surroundings that we did not distinguish between Them and Us. Maybe that contentment in the presence of the Now produced no thoughts of perfecting or making our bodies more desirable, of hiding behind frightening masks to teach our young ones a thing or two about The Wild Things out there, of showing off the completion of a rite of passage with an intricate tattoo or displaying our status and rank with a shimmering headdress. Perhaps in that blessed time before awareness of self, we were, indeed, in Paradise. But, in my humble opinion, the egoless animals roaming that land were not human beings.

We might not settle that one, but what’s certain is that as soon as we traded the Garden of Eden for our planet’s visual delights, it didn’t take long for those who could see, had two grabbing hands and a brain that could put two and two together, to endeavour to, somehow, appropriate this baffling immaterial material. A red apple was perhaps our demise (and spotted more easily by us), still, there was no question red ochre offered more colouring possibilities, and soon enough, everything became fair in love and… colour.

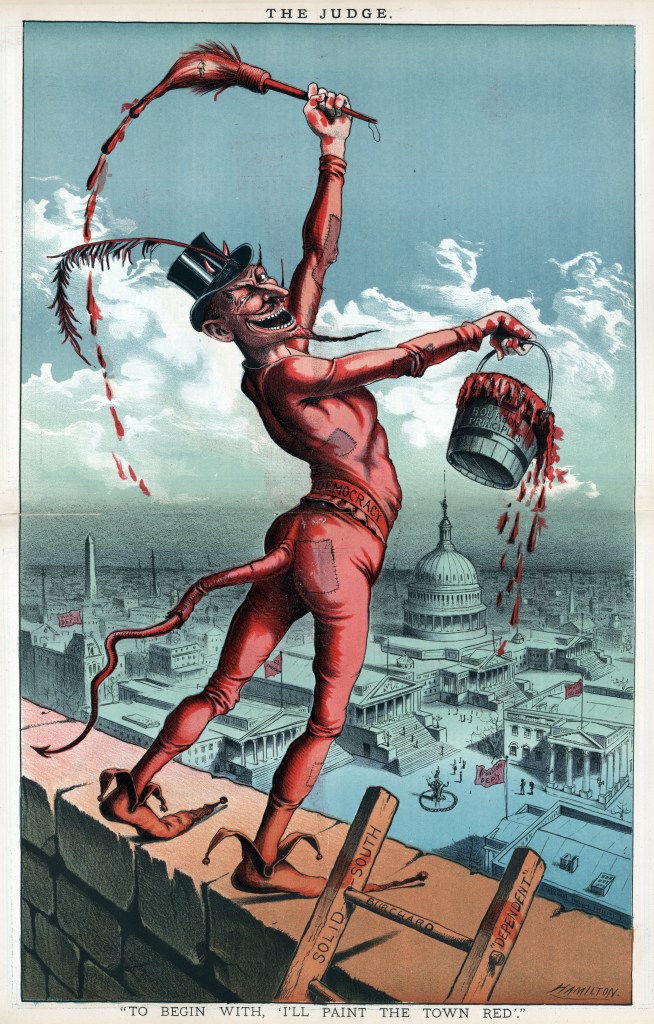

And when I say everything, I mean everything. In our relentless pursuit of a perfect red, a non-fugitive green or an intense, radiant purple, we stopped at nothing. Our human greed, maybe even need for the “resonant mysteries” which stirred our souls so, barred no practice, however… inhuman. Two devastating famines can be attributed to colour, a ‘red famine’ in Mexico and a ‘blue one’ in Bengal, both byproducts of imposed monocultures of cochineal and indigo. The south of France, which produced in 1881 half of the world’s madder, five years later, produced none; it was too heavily impacted by the discovery of synthetic dyes of higher tinting strength and involving less labour-intensive processes. While innumerable premature deaths due to slave labour in arsenic, lead or copper mines, logging in malaria-infested marshes or from the siliconing of lungs in ochre factories made even fewer waves. Despite all the issues in dealing with toxic substances, which we eventually understood well—not to mention the possible violation of sites sacred to previous landkeepers and the disruption to environments (such as soil rendered infertile, obnoxious smells, contaminated watercourses… and that’s woad cultivation I’m talking about not some acid mining practice!)—we kept (still keep!) those practices alive. Such is our desire for colourful clothes, colourful plates, colourful homes. The fact that our most basic needs—eating, sleeping in a safe place, clothing (keeping warm but also seducing a partner)—were in the race probably counts for far more in our determination to find stable colours than any needs of artists. Even if that connoisseur in the shadows, the very important, on some level, art market, did drive some of the steam.

In fact, traces of trial and error, trial and improvement, trial and success can be found in our oldest remaining marks. To the amazement of researchers, when they recently analysed the frescoes at Lascaux with a new non-invasive apparatus, where they expected Charcoal, an easily sourced but not very interesting paint pigment, or perhaps even Bone Black, they found complex mixtures of scarce manganese oxide minerals, including groutite, hausmannite, manganite and the rarer brownish blacks birnessite and todorokite.

After visiting the caves, Picasso apparently said: “We have invented nothing”, while another version goes: “Whomever these guys were, they were no beginners” (like that one better!) He was talking about their art, of course, not their use of Manganese Black and, yet, is taking the step to include their materials such a big one? Can we muse that these forefathers and mothers were pigment experts, probably not, but had gained an understanding of them sufficient enough to go to great lengths to obtain better ones? If so, how far and for how long had colour routes to source these beauties existed? In that precise case, and if the pigments came from there, the closest known Mn-rich geological site is a good 250 km away from Lascaux! I find daydreaming about this nearly as exciting as looking at their wondrous beasts, don’t you?

Still, it would be fair to say most discoveries were made when seeking new ceramic glazes, uniform threads in tapestries, elite toga hues or even a remedy for malaria rather than artists themselves coming up with new pigments. Not that they were very far from the production line mind you, having to select, grind their own pigments and turn them into paint, but maybe the scientific side of their brain was happily on the back burner while their artistic side was in full throttle. Nevertheless, you’d think Leonardo, on top of inventing machines to grind his pigments or beat gold leaves finer and perfecting binders for each of his glazing layers, could at least have come up with a new… a new… pink for example (since he apparently loved to dress in that colour!)

Jump to the next section of the book by clicking here

Alternatively click on the Table of Contents to browse the sections.

You can also subscribe to my blog at the bottom of this page,

and you’ll receive Hues in Tubes in your inbox… as it gets published!

Additional information & references

- Meloy, E. (2002). The Anthropology of Turquoise: Reflections on Desert, Sea, Stone, and Sky (1st Ed). Vintage Books, New York, NY, U.S.A. ↩︎

- I must plead guilty of that offense too, as madly in love with my pigment collection!! ↩︎

Discover more from in bed with mona lisa

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Dear Sabine,

I really enjoyed reading your chapter on colour. Your writing not only captivated me, but I also learned so many interesting facts.

You write so well—thank you for sharing!

Cxx💙